MENA INVESTIGATIVE REPORTERS

The LA story is important, but this website will focus on Mena as it is more connected to the boys' murders.

Two particularly important journalists have supported Linda for decades and have written extensively about Mena. They are Mara Leveritt, a liberal, and Micah Morrison, a conservative, again making the point that there is no room for political bias in responsible journalism. Their articles can be accessed from this page along with Daniel Hopsicker’s contributions to the Mena story.

Then there is the incomparable Sarah McClendon, an award-winning journalist, syndicated columnist, and Washington, D.C. Press Corp member whose career spanned the terms of eleven U.S. presidents from FDR to Clinton. She asked the hardball questions, which gave credibility to emerging stories and confidence to reporters that were pursuing them. Here, she caused Clinton to fumble for an answer that is now well known to be an absolute fabrication.

Micah Morrison

I’ve spent more than thirty years as a working writer and editor, mainly in investigative journalism, usually on complicated and controversial stories. In November 2013, I joined Judicial Watch as their chief investigative reporter. It’s a new age in journalism and a new chapter for me. I’m excited to be working with a great team of Freedom of Information Act investigators and litigators focused on government transparency and accountability.

Morrison's Reporting

June 29, 1994

The Wall Street Journal

Mysterious Mena

By Miach Morrison

MENA, Ark. — Reporters now trolling Arkansas are pulling up many stories that may have only fleeting relation to Whitewater or the Clintons, but are worth telling simply for their baroque charm. And none is more baroque than the tale of the Mena Intermountian Regional Airport, a site connected with aircraft renovation, apparent CIA operations and a self-confessed drug runner.

There is even one public plea that Special Counsel Robert Fiske should investigate possible links between Mena and the savings-and-loan association involved in Whitewater. The plea was sounded by the Arkansas Committee, a left-leaning group of former University of Arkansas students who have carefully tracked the Mena affair for years.

While a Whitewater connection is purely speculative, Mena certainly does seem a fruitful opportunity for thorough investigation, by Mr. Fiske or any other competent authority. It’s clear that at Mena Airport unusual things took place.

What the Arkansas Committee calls the “complex of events” surrounding Mena is the stuff of spy novels and thrillers, potentially including smuggling, CIA and Drug Enforcement Agency covert operations, money laundering and murder. There is no reliable evidence linking any of these events to Bill Clinton, except that he was governor of Arkansas when state and federal investigations of Mena were frustrated.

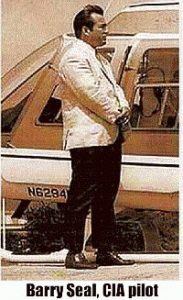

Mena is a good setting for a mystery. The pine and hardwood forests of the Ouachita Mountains surrounding it have long been an outlaw’s paradise, home to generations of moonshiners and red-dirt marijuana farmers. In 1981, cocaine smuggler Adler Berriman (“Barry”) Seal arrived on the scene, establishing a base of operations at Mena Airport. Mr. Seal’s record is well-known to law-enforcement officials; he often claimed to have made more than $50 million from his illegal activities.

Working out of a hangar at Rich Mountain Aviation, one of the local businesses that was turning Mena into a center for aircraft refurbishment, Mr. Seal imported as much as 1,000 pounds of cocaine a month from Colombia in the early 1980s, according to Arkansas State Police Investigator Russell Welch, who pursued the Seal case for over a decade. In 1984, Mr. Seal “rolled over” for the DEA, becoming one of its most important informants. He flew to Colombia and gathered information about leaders of the Medellin cartel, including drug kingpin Carlos Lehder, and testified in other high-profile cases.

He also flew at least two drug runs to Nicaragua, one of them entangling him in the Reagan administration’s anti-Sandinista effort. On a mission in mid-1984, Mr. Seal later testified, the CIA rigged a hidden camera in his C-123K cargo plane, enabling him to snap photos of several men loading cocaine aboard the aircraft — one of them allegedly an aide to Sandinista Interior Minister Tomas Borge.

Back at Mena, meanwhile, Mr. Seal’s business associate, Fred Hampton, the owner of Rich Mountain Aviation, purchased a land tract near the tiny backwoods community of Nella, 10 miles north of Mena, and cut a runway into it. Local law enforcement officials believe the land was purchased at the behest of Mr. Seal.

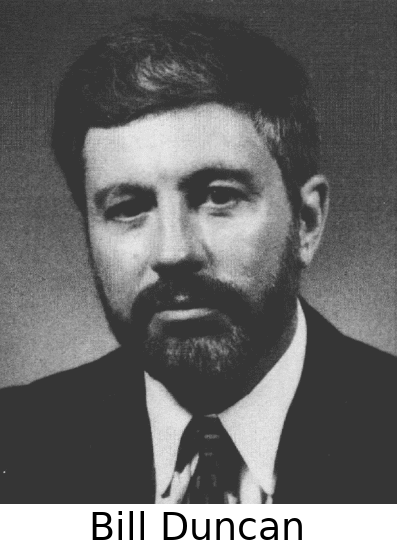

By 1984, reports were filtering in about odd military-type activity around Nella. “We had numerous reports of automatic weapons fire, men of Latin American appearance in the area, people in camouflage moving quietly through streams with automatic weapons, aircraft drops, twin-engine airplane traffic, things like that,” says former Internal Revenue Service Investigator William Duncan, who began investigating Mena in 1983. Residents of the countryside around Nella confirm reports of planes dropping loads in the mid-1980s. “But people don’t talk much about that around here,” said one local resident. “If you do, you might wake up one morning to find a bunch of your cattle dead.”

Mr. Duncan and Mr. Welch, the Arkansas State Police investigator, pressed forward with their probes of Mr. Seal and Rich Mountain Aviation. They suspected that Mr. Seal, despite his deal with the DEA, was continuing to import drugs and launder the money through local businesses and banks, possibly using the Nella airstrip as a base for drug drops.

In 1986, Mr. Seal’s wild ride came to an end. Three Colombian hitmen armed with machine guns caught up with him as he sat behind the wheel of his white Cadillac in Baton Rouge, La., and blasted him to his eternal reward. Eight months after the murder, Mr. Seal’s cargo plane was shot down over Nicaragua. Aboard was a load of ammunition and supplies for the Contras. One crew member, Eugene Hasenfus, survived. With the crash, and the Iran-Contra affair surfacing, investigators started looking at the

Nella airstrip in a new light. Maybe Barry Seal was not just flying drugs into the U.S. Maybe he also was flying newly trained Contras and weapons out.

But if Mr. Seal’s odyssey was over, the long and frustrating journey for Mena investigators was just beginning. Messrs. Duncan and Welch believed they had pieced together information on a significant drug smuggling operation, perhaps cloaked in the guise of a covert CIA operation, or perhaps in some way connected to the intelligence community. Yet repeated attempts to bring the Mena affair before grand juries in Arkansas, Gov. Bill Clinton, and federal authorities all failed, meeting a wall of obfuscation and obstruction.

The “CBS Evening News,” one of the few national news organizations to take a serious and discriminating look at Mena, recently broadcast an interview with Charles Black, a prosecutor for Polk County, in which Mena is located. He said he met with Gov. Clinton in 1988 and requested assistance for a state probe. “His response,” Mr. Black said, “was that he would get a man on it and get back to me. I never heard back.”

Asked for comment, White House spokesman John Podesta cites a state government offer of $25,000 to aid a Polk County investigation, an offer long under dispute in Arkansas. “The governor took whatever action was available to him,” Mr. Podesta says. “The failing in this case rests with the Republican Justice Department.”

Following pressure from then-Arkansas Rep. Bill Alexander, the General Accounting Office opened a probe in April 1988; within four months, the inquiry was shut down by the National Security Council. Several congressional subcommittee inquiries sputtered into dead ends.

In 1991, Arkansas Attorney General Winston Bryant presented Iran-Contra prosecutor Lawrence Walsh with what Mr. Bryant called “credible evidence of gunrunning, illegal drug smuggling, money laundering and the governmental coverup and possibly a criminal conspiracy in connection with the Mena Airport.” Seventeen months later, Mr. Walsh sent Mr. Bryant a letter saying without explanation that he had closed his investigation.

Mr. Duncan resigned from the IRS after repeatedly clashing with his superiors over the Mena affair. Mr. Welch was given a number of strong hints that he should devote his energies elsewhere. “I believe there was a coverup of events at Mena,” Mr. Duncan says. “We don’t really know what happened out there. Every time I tried to follow the money trail into central Arkansas, I ran into roadblocks.”

But what, if anything, does Mena have to do with Whitewater? A small conspiracy-theory industry has grown up around the mysteries of Mena. In a new book, “Compromised: Clinton, Bush and the CIA,” authors Terry Reed and John Cummings claim that Gov. Clinton and his inner circle, along with Lt. Col. Oliver North and the CIA, were involved in a conspiracy that included training Contras at Nella, sending weapons to Central America, smuggling cocaine into the U.S. and laundering funds through Arkansas banks. Little hard evidence is presented to back up these startling claims, yet the book should not be dismissed out of hand. Certainly, something was going on at Mena and Nella. And the authors raise the interesting question: What happened to all of Barry Seal’s cocaine money?

In an intriguing coincidence, while running Barry Seal as an agent, the DEA also was conducting an investigation into the drug-related activities of Little Rock bond dealer and Clinton supporter Dan Lasater. In October 1986, as Mr. Lasater was being charged in Little Rock with conspiracy to distribute cocaine, the DEA confirmed that he was the target of a drug-trafficking probe involving his private plane and a small airfield at the New Mexico ski resort Angel Fire, which Mr. Lasater purchased in 1984.

Mr. Lasater’s bond shop also executed a mysterious series of trades on behalf of Kentucky resident Dennis Patrick, who says he had no knowledge of the millions in trades reflected in his account in 1985 and 1986. It’s unclear what these trades represent, since Mr. Patrick’s confirmation slips show only paper transactions, with little money in or out. Yet it’s interesting to note that the hectic activity in the account came to an abrupt halt in February 1986 — the month Barry Seal was killed.

Of course, it all may be just a coincidence, and perhaps Gov. Clinton did not even know that drug smugglers, the CIA and the DEA were operating in his backyard. Perhaps he did not want to know. After all, as we have come to learn, Bill Clinton’s Arkansas was a very strange place.

Mr. Morrison is a Wall Street Journal editorial page writer.

Copyright © 1996 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Reproduced with Permission

October 18, 1994

The Wall Street Journal

Editorial Feature

The Mena Coverup

By Micah Morrison

MENA, Ark. – What do Bill Clinton and Oliver North have in common, along with the Arkansas State Police and the Central Intelligence Agency? All probably wish they had never heard of Mena.

President Clinton was asked at his Oct. 7 press conference about Mena, a small town and airport in the wilds of Western Arkansas. Sarah McClendon, a longtime Washington curmudgeon renowned for her off-the-wall questions, wove a query around the charge that a base in Mena was “set up by Oliver North and the CIA” in the 1980s and used to “bring in planeload after planeload of cocaine” for sale in the U.S., with the profits then used to buy weapons for the Contras. Was he told as Arkansas governor? she asked.

“No,” the president replied, “they didn’t tell me anything about it.” The alleged events “were primarily a matter for federal jurisdiction. The state really had next to nothing to do with it. The local prosecutor did conduct an investigation based on what was in the jurisdiction of state law. The rest of it was under the jurisdiction of the United States Attorneys who were appointed successively by previous administrations. We had nothing – zero – to do with it.”

It was Mr. Clinton’s lengthiest remark on the murky affair since it surfaced nearly a decade ago, in the middle of his long tenure as governor of Arkansas. And while the president may be correct to suggest that Mena is an even bigger problem for previous Republican administrations, he was wrong on just about every other count. The state of Arkansas had plenty to do with Mena, and Mr. Clinton left many unanswered questions behind when he to Washington.

Anyone who thinks that Mena is not serious should speak to William Duncan, a former Internal Revenue Service investigator who, together with Arkansas State Police Investigator Russell Welch, has fought a bitter 10-year battle to bring the matter to light. They pinned their hopes on nine separate state and federal probes. All failed.

“The Mena investigations were never supposed to see the light of day,” says Mr. Duncan, now an investigator with the Medicaid Fraud Division of the office of Arkansas Attorney General Winston Bryant “Investigations were interfered with and covered up, and the justice system was subverted.”

The mysteries of Mena, detailed on this page on June 29, center on the activities of a drug-smuggler-turned-informant named Adler Berriman “Barry” Seal. Mr. Seal began operating at Mena Intermountain Regional Airport in 1981. At the height of his career, according to Mr. Welch, Mr. Seal was importing as much as 1,000 pounds of cocaine a month.

By 1984, Mr. Seal was an informant for the Drug Enforcement Agency and flew at least one sting operation to Nicaragua for the CIA, a mission known to have drawn the attention of Mr. North. By 1986, Mr. Seal was dead, gunned down by Colombian hitmen in Baton Rouge, La. Eight months after Mr. Seal’s murder, his cargo plane, which had been based at Mena, was shot down over Nicaragua with Eugene Hasenfus and a load of Contra supplies aboard.

According to Mr. Duncan and others, Mr. Clinton’s allies in state government worked to suppress Mena investigations. In 1990, for example, when Mr. Bryant made Mena an issue in the race for attorney general, Clinton aide Betsey Wright warned the candidate “to stay away” from the issue, according to a CBS Evening News investigative report. Ms. Wright denies the report. Yet once in office, and after a few feints in the direction of an investigation, Mr. Bryant stopped looking into Mena.

Documents obtained by the Journal show that as Gov. Clinton’s quest for the presidency gathered steam in 1992, his Arkansas allies took increasing interest in Mena. Marie Miller, then director of the Medicaid Fraud Division, wrote in an April 1992 memo to her files that she told Mr. Duncan of the attorney general’s “wish to sever any ties to the Mena matter because of the implication that the AG might be investigating the governor’s connection.” The memo says the instructions were pursuant to a conversation with Mr. Bryant’s chief deputy, Royce Griffin. In an interview, Mr. Duncan said Mr. Griffin put him under “intense pressure” regarding Mena.

Another memo, from Mr. Duncan to several high-ranking members of the attorney general’s staff in March 1992, notes that Mr. Duncan was instructed “to remove all files concerning the Mena investigation from the attorney general’s office.” At the time, several Arkansas newspapers were known to be preparing Freedom of Information Act requests aimed at Gov. Clinton’s administration.

A spokesman for Mr. Bryant, Lawrence Graves, said yesterday that he was not aware of the missing files or of pressure exerted on Mr. Duncan. In Arkansas, Mr. Graves said, the attorney general “does not have authority” to pursue criminal cases.

From February to May 1992, Mr. Duncan was involved in a series of meetings aimed at deciding how to use a $25,000 federal grant obtained by then-Rep. Bill Alexander for the Mena investigation. In a November 1991 letter to Arkansas State Police Commander Tommy Goodwin, Mr. Alexander urged that, at the current “critical stage” in the Mena investigation, the money be used to briefly assign Mr. Duncan to the Arkansas State Police to pursue the case full time with State Police Investigator Welch and to prepare “a steady flow of information” for Iran-Contra prosecutor Lawrence Walsh, who had received some Mena files from Mr. Bryant.

According to Mr. Duncan’s notes on the meetings, Mr. Clinton’s aides closely tracked the negotiations over what to do with the money. Mr. Duncan says a May 7, 1992, meeting with Col. Goodwin was interrupted by a phone call from the governor, though he does not know what was discussed. The grant, however, was never used. Col. Goodwin told CBS that the money was returned “because we didn’t have anything to spend it on.”

In 1988, local authorities suffered a similar setback after Charles Black, a Mena-area prosecutor, approached Gov. Clinton with a request for funds for a Mena investigation. “He said he would get on it and would get a man back to me,” Mr. Black told CBS. “I never heard back.”

In 1990, Mr. Duncan informed Col. Goodwin about Clinton supporter Dan Lasater, who had been convicted of drug charges. “I told Tommy Goodwin that I’d received allegations of a Lasater connection to Mena,” Mr. Duncan said.

The charge, that Barry Seal had used Mr. Lasater’s bond business to launder drug money, was raised by a man named Terry Reed. Mr. Reed and journalist John Cummings recently published a book— “Compromised Clinton Bush and the CIA” – charging that Mr. Clinton, Mr. North and others engaged in a massive conspiracy to smuggle cocaine, export weapons and launder money. While much of the book rests on slim evidence and already published sources, the Lasater-Seal connection is new. (Thomas Mars, Mr. Lasater’s attorney, said yesterday that his client “has never had a connection” with Mr. Seal.) But when Mr. Duncan tried to check out the allegations, his probe went nowhere, stalled from lack of funds and bureaucratic hostility.

Not all of the hostility came from the state level. When Messrs. Duncan and Welch built a money-laundering case in 1985 against Mr. Seal’s associates, the U.S. Attorneys in the case “directly interfered with the process,” Mr. Duncan said. “Subpoenas were not issued, witnesses were discredited, interviews with witnesses were interrupted, and the wrong charges were brought before the grand jury.”

One grand jury member was so outraged by the prosecutors’ actions that she broke the grandjury secrecy covenant. Not only had the case been blatantly mishandled, she later told a congressional investigator, but many jurors felt “there was some type of government intervention,” according to a transcript of the statement obtained by the Journal. “Something is being covered up.”

In 1987, Mr. Duncan was asked to testify before a House subcommittee on crime. Two days before his testimony, he says, IRS attorneys working with the U.S. Attorney for Western Arkansas reinterpreted Rule 6(e), the grandjury secrecy law, forcing the exclusion of much of Mr. Duncan’s planned testimony and evidence. Mr. Duncan also charges that a senior IRS attorney tried to force him to commit perjury by directing him to say he had no knowledge of a claim by Mr. Seal that a large bribe had been paid to Attorney General Edwin Meese. Mr. Duncan says he didn’t make much of the drug dealer’s claim, but did know about it; he refused to lie to Congress.

Mr. Duncan, distressed by the IRS’s handling of Mena, resigned in 1989. Meanwhile, the affair was sputtering through four federal forums, including a General Accounting Office probe derailed by the National Security Council. At one particularly low point, Mr. Duncan, then briefly a Mena investigator for a House subcommittee, was arrested on Capitol Hill on a bogus weapons charge that was held over his head for nine months, then dismissed. His prized career in law enforcement in ruins, he found his way back to Arkansas and began to pick up the pieces.

Mr. Duncan does not consider President Clinton a political enemy. Indeed, he feels close to the president – a fellow Arkansan who shares the same birthday – and thinks Mena may turn out to be far more troublesome for GOP figures such as Mr. North than any Arkansas players.

These days, Mr. Duncan struggles to keep hope alive. “I’m just a simple Arkansan who takes patriotism very seriously,” he says. “We are losing confidence in our system. But I still believe that somewhere, somehow, there is some committee or institution that can issue subpoenas, get on the money trail, find out what happened and restore a bit of faith in the system.”

Mr. Morrison is a Journal editorial page writer.

Copyright © 1997 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Reproduced with Permission

April 7, 1995

The Wall Street Journal

Review and Outlook

Mena Again

By Micah Morrison

The strange story of what was going on at an airport in Mena, Arkansas, 10 years ago is an embarrassment to both the Democratic governor who ran Arkansas in the 1980s and to the Republicans who ran the White House. But two dogged Arkansans, former Internal Revenue Service Investigator William Duncan and Arkansas State Police Investigator Russell Welch, have kept the story alive. For more than a decade, Messrs. Duncan and Welch have been stitching together evidence of Mena-related schemes to smuggle drugs, launder money and ship weapons, possibly involving both Arkansas law enforcement and the U.S. intelligence community.

On Tuesday, Mr. Welch was summoned to Little Rock to appear before the State Police Commission. A review panel had demanded his immediate transfer to Little Rock. The reason? Inadequate attention to paperwork and the “need for closer supervision,” says Wayne Jordan, a police spokesman. “It has nothing to do with” the Mena probe.

Repeated attempts to bring the Mena affair before state and federal authorities have failed. Mr. Duncan’s stubborn insistence on investigating Mena, detailed on this page October 18, resulted in the destruction of his career in federal law enforcement. So naturally, when his colleague Russell Welch finds himself in a disciplinary hearing before the State Police Commission, we think it at least worthy of public note regardless of the official explanation. One year short of qualifying for his pension, Mr. Welch’s transfer clearly would be tantamount to demotion and prelude to dismissal.

Mr. Welch tells us that his troubles started a little over a year ago, when he responded to inquiries from The Wall Street Journal and “CBS Evening News.” Until then, he says he had always received above-average ratings on his performance reviews and high marks from his peers. Suddenly, questions were being raised about his paperwork. On one occasion, Mr. Welch says his commander, Major Charles Bolls, the chief of the Criminal Investigation Division complained that Mr. Welch was “becoming like the two troopers” who provided the press with details on Governor Clinton’s alleged sexual misadventures. In February, a police panel persistently questioned him about whether he was writing a book about Mena.

Two weeks ago, Mr. Welch was notified of the administrative hearing and ordered not to work on his appeal during office hours. Among those rising to his defense was Charles Black, a former Mena-area public prosecutor who once had attempted to investigate the drug charges surrounding the airfield. Today Mr. Black is a deputy county prosecutor in Texarkana. Concerned about what was happening to Mr. Welch, who had no lawyer to represent him, Mr. Black went to Tuesday’s hearing in Little Rock.

There, Mr. Black got the opportunity to question Major Bolls. According to observers of the proceeding, Major Bolls grew agitated when questioned about the Mena investigation and denied that it had anything to do with the transfer. Mr. Welch, Major Bolls said, was “consumed” with Mena and needed to be brought to Little Rock “so we would know where he was and what he was doing.” By day’s end, Mr. Black had won a 30-day continuance and Mr. Welch was placed on paid administrative leave.

A conflict of interest most likely prevents Mr. Black from further involvement in the case. He told us, however, “I’m convinced that Russell’s activities in investigating Mena and talking to the media are playing a role in this whole mess.” Mr. Jordan, the state police spokesman, hints that Mr. Welch’s personnel file contains more damaging information and urges Mr. Welch to OK its release. At the least, Russell Welch clearly needs a lawyer, and a very tough one at that.

Mr. Welch’s new lawyer might want to talk to Linda Ives, who drove up to Little Rock for the hearing. In 1987, Mrs. Ives’s teenage son Kevin and his friend Don Henry were murdered near the railroad tracks south of Little Rock. She has waged a long campaign to prove their deaths are linked to drugs and Mena and a coverup. This troubling incident was reported by the Los Angeles Times in May 1992.

“That hearing was not about a trooper who didn’t do his job,” Mrs. Ives told us. “It was about a trooper who did his job only too well. Anybody who tries to tell the story is discredited and ruined.”

Copyright © 1997 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Reproduced with Permission

HomeT

| The Wall Street Journal June 5, 1996 Edit Page Features Arkansas Reform In Hands Of Huckabee, StarrBy MICAH MORRISON In a stunning reversal for the political machine that has dominated Arkansas for decades, events in recent weeks have shoved the one-party state to the brink of historic reform. The May 28 resignation announcement of Gov. Jim Guy Tucker, convicted of bank fraud with James and Susan McDougal, is only the most visible sign of the shifting of the tectonic power plates. A week earlier, primary voters pointedly rejected or forced into runoffs candidates linked to the ruling elite, for the first time in Arkansas history fielding a strong statewide slate of Republicans. Speculating that the GOP could displace the Democrats in “one-party rule,” the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette editorialized, “It may take some getting used to. Like an earthquake.” Mike Huckabee is the young Republican lieutenant governor and Baptist preacher who will take the reins of state power when Mr. Tucker formally steps down. Mr. Huckabee said in an interview that he wants to be “a healer” for his state, but declined to discuss specific reforms before taking office. Yet in a sign perhaps of troubles ahead, Mr. Huckabee acknowledged he was “aware” of stories that state officials were shredding documents in anticipation of Gov. Tucker’s departure. “Anyone in a state agency or any state officer that would do something probably illegal — and certainly unethical — would have to be looked into,” Mr. Huckabee said. Gov. Huckabee will have a lot to look into, but he’d better watch his back. A good early move would be to start cleaning up the cesspool that is Arkansas law enforcement. Above all, he needs to put his own people in control of the Arkansas State Police. In Arkansas, the state police function as a kind of gubernatorial Praetorian Guard. Pimping for then-Gov. Clinton, it appears, was the least of their sins. Law enforcement officials say that the state police shut down cocaine probes into bond daddy Dan Lasater, chicken king Don Tyson and Roger Clinton before the investigations ran their course. There is abundant evidence that some members of the state police spent years undermining inquiries into alleged drug smuggling at Mena airfield, finally driving its own investigator, Russell Welch, out of a job. And in the controversial “train deaths” case, law enforcement officials seem to have thwarted investigations into apparent links between the murder of two teenagers, drugs, and a local prosecutor, Dan Harmon. Mr. Harmon is under investigation for a second time by the state police and FBI for corruption. He was jailed Friday for assaulting Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reporter Rodney Bowers, who tried to interview him about the probe. Mr. Bowers’s injuries aren’t serious, but the situation is painfully ironic. It’s widely believed in Arkansas journalistic circles that Mr. Bowers has not been encouraged to write all he knows about the train deaths and Mena cases, while his newspaper’s editorial page has expended much ink ridiculing stories on those subjects, particularly those by this writer. On May 21 voters decided they’d had enough of Mr. Harmon, denying him a spot on the Democratic ticket in a run for sheriff of Saline County. The GOP slot was won by John Brown, a former detective who investigated the train deaths. Mr. Brown says if elected he will “fight public corruption in all forms” and pursue the case. Voters also expressed their displeasure with Pulaski County Prosecuting Attorney Mark Stodola of Little Rock, forcing him into a runoff for the Democratic nomination for Rep. Ray Thornton’s congressional seat. If elected, Mr. Stodola will become the de facto head of a diminished but still dangerous political machine. A longtime Clinton ally, Mr. Stodola last week signaled that he is still willing to play bully boy for the power elite when he restated his intention to use his prosecutorial powers to bring state insurance fraud charges against key Whitewater witness David Hale. The message in any such Hale prosecution would be that new Whitewater witnesses are on notice that the state still has the power to punish them. This is not news to some of Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr’s witnesses, such as Judge Bill Watt, whose pension was revoked, or former Madison S&L officer Don Denton, who friends say is in danger of losing his job at Little Rock airport. Of course retribution is not news to Mena investigator Russell Welch. Nor is it news to Mr. Welch’s colleague, former IRS investigator Bill Duncan, whose career was destroyed because he pursued the truth in the Mena affair. Nor is it news to former local drug task force head Jean Duffey, who was run out of the state after investigating the train deaths and Mena. Nor of course is it news to the state troopers who came forward with stories of Bill Clinton’s sexual escapades, or to state police investigator J.N. “Doc” DeLaughter, whose career went down the drain after he started looking into Don Tyson and Dan Lasater. Gov. Huckabee no doubt will be cautious about his dealings with Mr. Starr, but the two likely will establish some kind of quiet symbiotic relationship. Mr. Starr already is far down the road of liberating Arkansas from corruption. Mr. Huckabee’s Baptist roots should allow him to do no less. The new governor can be of enormous help by signaling that state employees cooperating with Mr. Starr will not suffer retribution; let the truth set them free. And while he’s at it, Mr. Huckabee should indicate that he’s serious about getting to the bottom of Mena and the train deaths. He could start by consulting Bill Duncan, Russell Welch, Jean Duffey, Doc DeLaughter, and maybe even Rodney Bowers, about whom he should name to head the state police. Mr. Morrison is a Journal editorial page writer. Reproduced with permission |

January 29, 1997

The Wall Street Journal

Mysterious Mena: CIA Discloses, Leach Disposes

By Micah Morrison

The word on Capitol Hill is that Rep. Jim Leach will soon wrap up his inquiry into the spooky goings-on at remote Mena in western Arkansas. For more than a decade, state and federal probes of supposedly government-related drug smuggling, gun running and money laundering at Mena Intermountain Regional Airport have hit a stone wall. But Mr. Leach already can claim some success: He kept the pressure on the Central Intelligence Agency until it completed a still-classified internal probe of the allegations; in a declassifed summary released in November, the CIA for the first time admitted that it had a presence in Arkansas.

The agency was not “associated with money laundering, narcotics trafficking, arms smuggling, or other illegal activities” at Mena, the report concludes. But the CIA did engage in “authorized and lawful activities” at the airfield: a classified “joint-training operation with another federal agency” and contracting for “routine aviation-related services.”

At the center of the web of speculation spun around Mena are a few undisputed facts: One of the most successful drug informants in U.S. history, smuggler Barry Seal, based his air operation at Mena. At the height of his career he was importing as much as 1,000 pounds of cocaine per month, and had a personal fortune estimated at more than $50 million. After becoming an informant for the Drug Enforcement Administration, he worked at least once with the CIA, in a Sandinista drug sting. He was gunned down by Colombian hit men in Baton Rogue, La., in 1986; eight months later, one of his planes–with an Arkansas pilot at the wheel and Eugene Hasenfus in the cargo bay–was shot down over Nicaragua with a load of Contra supplies.

What had then-Gov. Bill Clinton known about CIA activities at Mena? Asked at an October 1994 press conference, President Clinton said, “They didn’t tell me anything about it.” Events at Mena, Mr. Clinton continued, “were primarily a matter for federal jurisdiction. The state really had next to nothing to do with it. The local prosecutor did conduct an investigation based on what was in the jurisdiction of state law. The rest of it was under the jurisdiction of the United States Attorneys who were appointed successively by previous administrations. We had nothing–zero–to do with it.”

Mr. Clinton was right about federal jurisdiction, but wrong about Arkansas involvement. As reported on this page, local attempts to investigate Mena were tanked twice by the Mr. Clinton’s administration in Little Rock, which refused to allocate funds. And in July 1995, a former member of Gov. Clinton’s security staff, Arkansas State Trooper L.D. Brown, suddenly stepped forward claiming he had worked with the CIA and Seal running guns to the Contras–and cocaine back to the U.S. Mr. Brown says that when he informed the governor about the drug flights, Mr. Clinton replied, “that’s Lasater’s deal”–a reference to Little Rock bond daddy Dan Lasater, a Clinton crony later convicted on an apparently unrelated cocaine distribution charge.

The CIA report does not directly address the Lasater allegation. It says trooper Brown applied to the agency but was not offered employment and was not “otherwise associated with CIA.” Barry Seal was associated with CIA, but only for “a two-day period” while his plane was being outfitted for the DEA’s Sandinista sting. The CIA also says it found no evidence of tampering in earlier money-laundering prosecutions, as several Arkansas investigators have charged.

And what does the CIA say about Mr. Clinotn’s knowledge of CIA activities at Mena? It gives its boss wiggle room that parses nicely with his statement that “they didn’t tell me anything.” In response to Mr. Leach’s question about whether information was conveyed to Arkansas officials in the 1980s, the report states that “interface with local officials was handled by the other federal agency” involved in the joint Mena exercise, side-stepping the issue of what Mr. Clinton knew.

The Clinton White House has gone to great lengths to discredit the Mena story. It figures in the notorious White House conspiracy report and was denounced by former Whitewater damage-control counsel Mark Fabiani as “the darkest backwater of right-wing conspiracy theories.” Beltway pundits tend to dismiss Mena as an excess of the Clinton critics. But in Arkansas the campaign is more vicious. With a passive press having long ago abandoned the field, Mena investigators such as former Arkansas State Police investigator Russell Welch and former IRS agent Bill Duncan were stripped of their careers after refusing to back away from the case. Mr. Leach’s CIA report provides some vindication for the two Arkansans.

Mr. Leach’s full report is not likely to resolve all the questions surrounding Mena, but it might provide important details about that “other agency” and related mysteries. In Arkansas, meanwhile, the Little Rock FBI office is following leads in a sensitive drug-corruption probe involving the Linda Ives “train deaths” case and allegations of Mena-related drug drops. The big drug-corruption question is what network encompassed the Barry Seal operation. The answer could come by following the money on some of the smaller questions, such as whether those CIA contracts for “aviation-related services” went to one of Seal’s front companies at Mena. But in forcing an admission from the U.S. intelligence community, Mr. Leach already has performed an important service: He’s demolished the notion that nothing happened at Mena.

Mr. Morrison is a Journal editorial page writer.

Copyright © 1997 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Reproduced with Permission

March 3, 1999

The Wall Street Journal

Commentary

A Place Called Mena

By Micah Morrison

Journal Editorial Page Writer

Reacting to the Juanita Broaddrick story, White House spokesman Joe Lockhart said the Journal editorial page “lost me after they accused the president of being a drug smuggler and a murderer.” We made no such charges, of course. But we’ll give Mr. Lockhart a pass on the grounds of hyperbole; we have indeed reported stories about the seamy side of Bill Clinton’s Arkansas.

Most of our stories–as opposed to gamier Arkansas tales traded on the Internet–have revolved around Mena Intermountain Regional Airport in western Arkansas. Even as careful an observer as David Frum, writing in Commentary, criticizes “wild charges” including “drug-smuggling via Mena airport.” Since drug smuggling at Mena is established beyond doubt, a brief review of some facts seems in order:

- Mena was a staging ground for Barry Seal, one of the most notorious drug smugglers in history. He established a base at Mena in 1981, and according to Arkansas law-enforcement officials, imported as much as 1,000 pounds of cocaine a month from Colombia. In 1984 he became an informant for the Drug Enforcement Administration, flying to Colombia and gathering information about leaders of the Medellín cartel. He testified in several high-profile cases, and was assassinated in Baton Rouge, La., in 1986.

- Two investigators probing events at Mena say they were closed down–William Duncan, a former Internal Revenue Service investigator, and Russell Welch, a former Arkansas State Police detective. They fought a decade-long battle to bring events at Mena to light, pinning their hopes on nine separate state and federal probes. All failed. And Messrs. Welch and Duncan were stripped of their careers.

- In 1986, Dan Lasater, Little Rock bond daddy and an important Clinton campaign contributor, pleaded guilty to cocaine distribution. The scheme also involved Mr. Clinton’s brother, Roger. Both Mr. Lasater and Roger Clinton served brief prison terms. Gov. Clinton later issued a pardon to Mr. Lasater.

- On Aug. 23, 1987, teenagers Kevin Ives and Don Henry were run over by a northbound Union Pacific train near Little Rock in an area reputed to be a haven for drug smugglers. Gov. Clinton’s state medical examiner, Fahmy Malak, quickly ruled the deaths accidental, saying the two boys had fallen into a deep sleep side by side on the railroad tracks after smoking too much marijuana. A second autopsy concluded the boys had been murdered and their bodies placed on the tracks. Despite public outcry, Dr. Malak remained medical examiner until just before Mr. Clinton’s presidential campaign.

- In 1990 Jean Duffey, the head of a newly created drug task force, began investigating a possible link between the train deaths and drugs. Her boss, the departing prosecuting attorney for Arkansas’s Seventh Judicial District, gave her a direct order: “You are not to use the drug task force to investigate public officials.” In a 1996 interview with the Journal, Ms. Duffey said: “We had witnesses telling us about low-flying aircraft and informants testifying about drug pick-ups.”

- Dan Harmon, who had earlier been appointed special prosecutor for the train deaths, took office in 1991 as seventh district prosecutor. Ms. Duffey was discredited, threatened, and ultimately forced to flee Arkansas. In 1997, a federal jury in Little Rock found Mr. Harmon guilty of five counts of drug dealing and extortion, and sentenced him to eight years in prison for using his office to extort narcotics and cash.

Mr. Lockhart to the contrary, we have never accused Mr. Clinton of a direct role in these events. Obviously, as governor for 12 years, he was ultimately responsible for Arkansas law enforcement. As president, he has commented only once about events at Mena. Asked about it during a 1994 press conference, he said that it was “primarily a matter of federal jurisdiction” and “they didn’t tell me anything about it.”

- In 1984, Seal flew his C-123K to Nicaragua in a Central Intelligence Agency drug sting of Sandinista officials. The CIA rigged a hidden camera in the plane, enabling him to snap photos of several men–including a high-ranking Sandinista–loading cocaine aboard the aircraft. In 1986, eight months after Seal’s death, his plane was shot down over Nicaragua with an Arkansas pilot at the wheel and a load of ammunition and contra supporter Eugene Hasenfus in the cargo bay.

- Three days after the 1996 presidential election, the CIA issued a brief report saying it had engaged in “authorized and lawful activities” at the airfield, including “routine aviation-related services” and a secret “joint-training operation with another federal agency.” The agency said it was not “associated with money laundering, narcotics trafficking, arms smuggling, or other illegal activities” at Mena.

The statement was issued in response to a probe by investigators for the House Banking Committee, directed by Chairman Jim Leach. His report has been often promised and often delayed. Yesterday Leach spokesman David Runkel said that Banking Committee investigators are “putting the finishing touches” on their report. “While there is an extraordinary story to be told, it’s unlikely that the president is going to be too severely embarrassed.” Whatever Mr. Clinton’s involvement as governor, something singular was going on at Mena. Perhaps Mr. Leach will yet shed some light on the mystery.

July 22, 2019

Judicial Watch

Guns, Drugs, CIA at Mena:

Judical Watch Demands Answers

By Micah Morrison

The mysterious events surrounding Mena Airfield in remote western Arkansas during the gubernatorial reign of Bill Clinton have teased the popular imagination for more than three decades. Movies have been made, books have been published, hundreds of articles have been written. Many of the more baroque allegations emerge from the fever swamps of conspiracy theorists, but certain facts are indisputable. CIA and DEA activities flowed out of Mena in the Clinton years. Cocaine—a lot of it—flowed in. And for thirty years, every attempt to get to the bottom of events at Mena—federal, state, judicial, journalistic—has failed.

Judicial Watch has launched a new campaign for answers. The CIA “stonewalled the release of information now sought by Judicial Watch on the Mena Airport controversy,” said Judicial Watch President Tom Fitton. So last month, we filed a lawsuit seeking a long-hidden report by the CIA inspector general into events at Mena. The Judicial Watch lawsuit seeks the report of a November 1996 CIA investigation into “drug running, money laundering and intelligence gathering” at Mena. We’re taking other steps, too—Freedom of Information actions against the DEA, FBI, and Arkansas state institutions.

I first traveled to Mena in 1994, reporting for the Wall Street Journal editorial page. “Mena is a good setting for a mystery,” I wrote at the time. “The pine and hardwood forests of the Ouachita Mountains surrounding it have long been an outlaw’s paradise, home to generations of moonshiners and red-dirt marijuana farmers.” It was also just seventy miles south of the sprawling Fort Chaffee Army Base at Fort Smith, Arkansas. I didn’t make the connection then, but it seems significant now: if you’re going to secretly run arms to controversial U.S. allies, you’ll likely want some military support.

The mysteries of Mena revolve around a drug-smuggling pilot named Barry Seal. In 1981, Seal set up shop at Mena. He later claimed to have made as much as $50 million running 1,000 pounds of cocaine a month from Colombia. In 1983, the DEA arrested him on drug smuggling charges. Seal flipped, becoming a valuable government informant.

He gathered information on Medellin cartel kingpins and participated in at least two drug runs to Nicaragua, where the Reagan administration was ramping up operations against the Sandinista government. On one CIA-involved mission in 1984, a secret camera in Seal’s C-123 cargo plane snapped photos of an alleged Sandinista official loading cocaine aboard the aircraft. The photos quickly leaked, boosting Washington’s anti-Sandinista effort but likely putting a target on Seal’s back: to his drug-running friends in South America, there could be no question where the photos came from.

In Mena, meanwhile, things were getting stranger. A Seal associate cut a runway deep in the woods. Bill Duncan, an IRS investigator, told me that he had “numerous reports of automatic weapons fire, men of Latin American appearance in the area, people in camouflage moving quietly through streams with automatic weapons, aircraft drops, twin-engine airplane traffic.” Duncan, along with Arkansas State Police investigator Russell Welch, started digging into Seal and the Mena connection, suspecting a drug smuggling and money laundering operation. For their efforts, their careers were crushed.

In 1986, Colombian hitmen caught up with Seal in Baton Rouge, shooting him to death in his white Cadillac. Eight months later, Seal’s C-123 was shot down over Nicaragua with a load of ammunition and supplies for the anti-Sandinista Contra rebels. Documents and a surviving crew member tied the shipment to the CIA and the White House, dragging a Seal connection into the Iran-Contra affair.

The story took on a new life when Bill Clinton ran for president. And while Clinton would later correctly note that events at Mena were “primarily a matter of federal jurisdiction”—meaning that Republicans probably had more to lose than Democrats if the truth was exposed—it’s also true that a Clinton friend and supporter named Dan Lasater was under investigation for drug smuggling at the same time Seal was operating in Arkansas. Lasater went to jail for a cocaine connection, as did his friend, Roger Clinton, Bill Clinton’s brother.

In 1996, House Banking Committee Chairman Jim Leach pressed the CIA for answers about its role at Mena. The CIA’s inspector general investigated and released a terse statement saying “no evidence has been found that the CIA was associated with money laundering, narcotics trafficking, arms smuggling or other illegal activities at or around Mena.” There was, however, a classified “two-week exercise” and some contracting for “routine aviation-related services.”

In other words: nothing to see here, move on. And move on, the world did. But twenty-three years later, Judicial Watch says it is time for answers. We’re suing the CIA for the full inspector general report and we want documents from other agencies as well.

Ancient history? Maybe not.

The respected Arkansas journalist Mara Leveritt recently outlined what appears to be a continuing effort to cover up the Mena affair. Leveritt has written convincing book-length studies of the Memphis Three case and the deaths of teenagers Don Henry and Kevin Ives, the Arkansas “boys on the tracks.” In “Who’s Afraid of Barry Seal?,” in the Arkansas Times, Leveritt wrote that “secrets… are still being carefully kept, especially in Arkansas.” In advance of the recent Tom Cruise movie about Seal, American Made, an official associated with the Arkansas Studies Institute, an affiliate of the University of Arkansas and the Central Arkansas Library—both state institutions—convinced Leveritt to write a book about Mena, as a tie-in to the movie.

Leveritt was reluctant at first, but soon warmed to the task and got to work. The book was to be called, “The Mena File: Barry Seal’s Ties to Drug Lords and U.S. Officials.” Leveritt knew the story well and had researched it earlier, writing about Seal’s murder and other related events. Suddenly, though, the Arkansas State Police were uncooperative. They could locate no files on Seal.

How could that be? “I knew the agency had an extensive file on Seal,” Leveritt wrote, “because I’d read it decades earlier, shortly after Seal’s murder. In fact, I still had a letter from the former director advising me, in case I’d planned to make copies, that the file held some 3,000 pages.”

Leveritt had in-depth knowledge of the travails of investigators Duncan and Welch, and state and federal officials, in attempting to get to the truth about Mena. Yet she pressed on with her writing and finished the book. An index was completed and the book was listed in the University of Arkansas Press catalog.

“But I was in for a shock,” Leveritt writes. The book was killed at the last minute.

No convincing explanation was offered for this act of censorship. Officials at the Arkansas Studies Institute suggested their concerns were legal and financial, associated with vetting the book, but Leveritt wasn’t buying it. She was an experienced writer and had prepared for the legal review. No one responded when she asked if “the newly arisen concerns might be political.”

In the Arkansas Times article, Leveritt pinned her hopes on the new Cruise movie, which opened in 2017 to good reviews. “Too many secrets have been kept for too long,” she wrote, “too much important history has been hidden, lost or destroyed. Let’s hope that Cruise’s high-powered version of Seal prompts an equally high-powered demand for disclosure of all government records on him, especially after his move to Mena.”

That didn’t happen. We’ll take it from here.

***

Micah Morrison is chief investigative reporter for Judicial Watch. Follow him on Twitter @micah_morrison. Tips: mmorrison@judicialwatch.org

Investigative Bulletin is published by Judicial Watch. Reprints and media inquiries: jfarrell@judicialwatch.org

July 26,2019

Judical Watch

Mysterious Mena: Judicial Watch Demands Answers

By Micah Morrison

The mysterious events surrounding Mena Airfield in remote western Arkansas during the gubernatorial reign of Bill Clinton have teased the popular imagination for more than three decades. Movies have been made, books have been published, hundreds of articles have been written. Many of the more baroque allegations emerge from the fever swamps of conspiracy theorists, but certain facts are indisputable. CIA and DEA activities flowed out of Mena in the Clinton years. Cocaine—a lot of it—flowed in. And for thirty years, every attempt to get to the bottom of events at Mena—federal, state, judicial, journalistic—has failed.

Judicial Watch has launched a new campaign for answers. The CIA “stonewalled the release of information now sought by Judicial Watch on the Mena Airport controversy,” said Judicial Watch President Tom Fitton. So last month, we filed a lawsuit seeking a long-hidden report by the CIA inspector general into events at Mena. The Judicial Watch lawsuit seeks the report of a November 1996 CIA investigation into “drug running, money laundering and intelligence gathering” at Mena. We’re taking other steps, too—Freedom of Information actions against the DEA, FBI, and Arkansas state institutions.

I first traveled to Mena in 1994, reporting for the Wall Street Journal editorial page. “Mena is a good setting for a mystery,” I wrote at the time. “The pine and hardwood forests of the Ouachita Mountains surrounding it have long been an outlaw’s paradise, home to generations of moonshiners and red-dirt marijuana farmers.” It was also just seventy miles south of the sprawling Fort Chaffee Army Base at Fort Smith, Arkansas. I didn’t make the connection then, but it seems significant now: if you’re going to secretly run arms to controversial U.S. allies, you’ll likely want some military support.

The mysteries of Mena revolve around a drug-smuggling pilot named Barry Seal. In 1981, Seal set up shop at Mena. He later claimed to have made as much as $50 million running 1,000 pounds of cocaine a month from Colombia. In 1983, the DEA arrested him on drug smuggling charges. Seal flipped, becoming a valuable government informant.

He gathered information on Medellin cartel kingpins and participated in at least two drug runs to Nicaragua, where the Reagan administration was ramping up operations against the Sandinista government. On one CIA-involved mission in 1984, a secret camera in Seal’s C-123 cargo plane snapped photos of an alleged Sandinista official loading cocaine aboard the aircraft. The photos quickly leaked, boosting Washington’s anti-Sandinista effort but likely putting a target on Seal’s back: to his drug-running friends in South America, there could be no question where the photos came from.

In Mena, meanwhile, things were getting stranger. A Seal associate cut a runway deep in the woods. Bill Duncan, an IRS investigator, told me that he had “numerous reports of automatic weapons fire, men of Latin American appearance in the area, people in camouflage moving quietly through streams with automatic weapons, aircraft drops, twin-engine airplane traffic.” Duncan, along with Arkansas State Police investigator Russell Welch, started digging into Seal and the Mena connection, suspecting a drug smuggling and money laundering operation. For their efforts, their careers were crushed.

In 1986, Colombian hitmen caught up with Seal in Baton Rouge, shooting him to death in his white Cadillac. Eight months later, Seal’s C-123 was shot down over Nicaragua with a load of ammunition and supplies for the anti-Sandinista Contra rebels. Documents and a surviving crew member tied the shipment to the CIA and the White House, dragging a Seal connection into the Iran-Contra affair.

The story took on a new life when Bill Clinton ran for president. And while Clinton would later correctly note that events at Mena were “primarily a matter of federal jurisdiction”—meaning that Republicans probably had more to lose than Democrats if the truth was exposed—it’s also true that a Clinton friend and supporter named Dan Lasater was under investigation for drug smuggling at the same time Seal was operating in Arkansas. Lasater went to jail for a cocaine connection, as did his friend, Roger Clinton, Bill Clinton’s brother.

In 1996, House Banking Committee Chairman Jim Leach pressed the CIA for answers about its role at Mena. The CIA’s inspector general investigated and released a terse statement saying “no evidence has been found that the CIA was associated with money laundering, narcotics trafficking, arms smuggling or other illegal activities at or around Mena.” There was, however, a classified “two-week exercise” and some contracting for “routine aviation-related services.”

In other words: nothing to see here, move on. And move on, the world did. But twenty-three years later, Judicial Watch says it is time for answers. We’re suing the CIA for the full inspector general report and we want documents from other agencies as well.

Ancient history? Maybe not.

The respected Arkansas journalist Mara Leveritt recently outlined what appears to be a continuing effort to cover up the Mena affair. Leveritt has written convincing book-lengthstudies of the Memphis Three case and the deaths of teenagers Don Henry and Kevin Ives, the Arkansas “boys on the tracks.” In “Who’s Afraid of Barry Seal?,” in the Arkansas Times, Leveritt wrote that “secrets… are still being carefully kept, especially in Arkansas.” In advance of the recent Tom Cruise movie about Seal, American Made, an official associated with the Arkansas Studies Institute, an affiliate of the University of Arkansas and the Central Arkansas Library—both state institutions—convinced Leveritt to write a book about Mena, as a tie-in to the movie.

Leveritt was reluctant at first, but soon warmed to the task and got to work. The book was to be called, “The Mena File: Barry Seal’s Ties to Drug Lords and U.S. Officials.” Leveritt knew the story well and had researched it earlier, writing about Seal’s murder and other related events. Suddenly, though, the Arkansas State Police were uncooperative. They could locate no files on Seal.

How could that be? “I knew the agency had an extensive file on Seal,” Leveritt wrote, “because I’d read it decades earlier, shortly after Seal’s murder. In fact, I still had a letter from the former director advising me, in case I’d planned to make copies, that the file held some 3,000 pages.”

Leveritt had in-depth knowledge of the travails of investigators Duncan and Welch, and state and federal officials, in attempting to get to the truth about Mena. Yet she pressed on with her writing and finished the book. An index was completed and the book was listed in the University of Arkansas Press catalog.

“But I was in for a shock,” Leveritt writes. The book was killed at the last minute.

No convincing explanation was offered for this act of censorship. Officials at the Arkansas Studies Institute suggested their concerns were legal and financial, associated with vetting the book, but Leveritt wasn’t buying it. She was an experienced writer and had prepared for the legal review. No one responded when she asked if “the newly arisen concerns might be political.”

In the Arkansas Times article, Leveritt pinned her hopes on the new Cruise movie, which opened in 2017 to good reviews. “Too many secrets have been kept for too long,” she wrote, “too much important history has been hidden, lost or destroyed. Let’s hope that Cruise’s high-powered version of Seal prompts an equally high-powered demand for disclosure of all government records on him, especially after his move to Mena.”

That didn’t happen. We’ll take it from here.

***

Micah Morrison is chief investigative reporter for Judicial Watch. Follow him on Twitter @micah_morrison. Tips: mmorrison@judicialwatch.org

Investigative Bulletin is published by Judicial Watch. Reprints and media inquiries: jfarrell@judicialwatch.org

June 29, 2020

Judicial Watch

Investigative Bulletin

Mena Uncovered: Judicial Watch Discloses Secret CIA Report

By Micah Morrison

Judicial Watch recently obtained new documents related to mysterious Mena Airfield in Arkansas. They shed more light on what happened at Mena and what then-Governor Bill Clinton knew about it.

Strange events unfolded at Mena, a small city in remote western Arkansas, in the 1980s. When Bill Clinton became president, Mena got a closer look. Evidence emerged suggesting that the CIA was operating in the area in the early 1980s; that a major cocaine and gun smuggler was based at the airfield; and that the U.S. military was somehow involved. Conspiracy theories sprouted. The Clinton Administration batted away concerns about Mena as the rantings of its right-wing enemies.

At a 1994 news conference, in his only statement about Mena, President Clinton dodged a question about what he knew when he was governor. Federal authorities “didn’t tell me anything about it,” he said, noting that the events “were primarily a matter for federal jurisdiction.” He added, “we had nothing—zero—to do with it.”

In 1996, the House Banking Committee asked the CIA to report on its involvement at Mena and whether it had any connection to money laundering, narcotics trafficking, or arms smuggling in the area. The CIA report was given a “Secret” classification and not released to the public. In a brief public statement, the CIA said it had no connection to illegal activities in the region, but it did participate in a classified “joint training operation with another federal agency” and conducted at Mena Airfield “routine aviation-related services on equipment owned by the CIA.”

And that’s where the official government response ended.

Until now.

Responding to Freedom of Information pressure from Judicial Watch, the CIA released a highly redacted version of the full Mena Report. You can read the secret report obtained by Judicial Watch here.

The big takeaway: Bill Clinton almost certainly knew more about Mena than he suggested in 1994. Clinton said that federal authorities “didn’t tell me anything about it.” That turns out to be a clever dodge. The report notes that “certain Arkansas state and local officials were informed” about CIA activities at Mena. That’s new.

For the first time, we learn that an unnamed official “personally briefed the supervisor of the Arkansas State Police district” for Mena, “the Mayor of Mena,” “the Mena Chief of Police or the county sheriff, and the person responsible for operating Mena Intermountain Airport” about the joint-training exercise with the CIA.

Now, in Arkansas in the 1980s, Gov. Clinton was famously wired in to everything happening in the state. You can bet that the state police supervisor, the mayor, the police chief, the county sheriff, or the airport manager was quickly on the phone to the governor. Probably all of them were.

What did that unnamed official tell local authorities? Sorry, that’s redacted on national security grounds.

Another significant takeaway from the report: the other federal agency involved in that joint training exercise in the Arkansas woods? It was the Defense Department. That’s new, too.

The report states that the “CIA participated in a Department of Defense (DoD) training exercise.”

When did this happen? Sorry, the date is redacted on national security grounds.

What exactly went on during that training exercise? Sorry, that information also is redacted on national security grounds.

In fact, practically the entire seven pages of the CIA report describing the joint Defense Department exercise is redacted.

What were those “routine aviation-related services at Mena” conducted on CIA equipment? Sorry, redacted on national security grounds—all four pages.

The report also considers whether the international drug smuggler Barry Seal was involved with the CIA. Seal is the locus for many of the elaborate conspiracy theories surrounding Mena, including that arms were shipped south by U.S. authorities to the Contras opposed to the Nicaraguan Sandinista regime and cocaine came back on the return trips. There’s no doubt Seal was a drug runner mixed up with arms smuggling. In 1986, Colombian hitmen killed him in Baton Rouge. Months later, a C-123 aircraft he had owned was shot down over Nicaragua with a load of arms destined for the Contras.

The CIA denied a Seal connection, saying he “was never employed by the CIA in any capacity.” They pin Seal’s government connections on the DEA, a charge supported by a lot of evidence.

As for the Seal’s Mena-related activities? The next 28 pages of the CIA report are blank—redacted on national security grounds.

Despite extensive redactions, aficionados of mysterious Mena learn a few things from the CIA report. We learn that Bill Clinton likely knew a lot more than he has admitted. That plenty of Arkansas officials were aware something was going on at Mena. That the CIA participated with the Department of Defense in a secret exercise in the Arkansas woods. And that the CIA contracted for extensive aircraft maintenance work at Mena airfield.

We also learn there is a lot the government still does not want us to know. So we’ve asked the CIA to conduct an official declassification review of the Mena Report. We want the full, unredacted report. “Mena is an enduring issue,” says Judicial Watch President Tom Fitton. “The Mena Report should be declassified and released. The public deserves answers to what really went on at Mena.”

***

Micah Morrison is chief investigative reporter for Judicial Watch. Follow him on Twitter @micah_morrison. Tips: mmorrison@judicialwatch.org

Investigative Bulletin is published by Judicial Watch. Reprints and media inquiries: jfarrell@judicialwatch.org

February 1, 2021

Judicial Watch

Mysterious Mena: Death of a Patriot

By Micah Morrison

I first met Russell Welch at a cheap motel on the outskirts of Mena, Arkansas, in the summer of 1994. It was a searing hot day and I had left the door open for some air and I heard a car slowly drive across the gravel and stop. I looked up and Russell’s gaunt shadow crossed the doorway.

I first met Russell Welch at a cheap motel on the outskirts of Mena, Arkansas, in the summer of 1994. It was a searing hot day and I had left the door open for some air and I heard a car slowly drive across the gravel and stop. I looked up and Russell’s gaunt shadow crossed the doorway.

He was no one’s idea of an Arkansas State Police investigator. Lean, with long brown hair and a handlebar mustache, soft-spoken, his face ravaged by anthrax that almost killed him in 1991, Russell had found himself on a case he never wanted and in the middle of a storm. The case was the investigation of drug smuggler Barry Seal and his activities at remote Mena Airfield in western Arkansas. The storm was Seal’s connections, real and imagined, to a network of government officials and their enablers, including the then-president of the United States, Bill Clinton.

Wall Street Journal editor Robert L. Bartley had sent me to Mena to figure out what was going on. CBS had been there before me. A legion of journalists and con men and grifters and government investigators would follow.

The Mena story is part of the cultural conspiracy landscape now. You can read about Judicial Watch’s latest investigation here, and find more background on the case here. Or you can watch the movie starring Tom Cruise. Or the other movie starring Dennis Hopper.

Russell believed that the conspiracy mischief that engulfed Mena was mainly due to Terry Reed’s book, “Compromised: Clinton, Bush, and the CIA.” It spins a vast, largely fictional tale about a drugs-for-money-for-guns conspiracy involving Bill Clinton, George H.W. Bush, infamous CIA operatives, Arkansas associates of the Clintons, Oliver North, Seal, Reed himself, Reagan Administration figures, the FBI, the Justice Department, members of Congress, criminals, Contras, cocaine cowboys, and a partridge in a pear tree.

But as Bartley recognized, most conspiracy theories contain a grain of truth, maybe even a few grains of truth. So he sent me down to Arkansas to look for it.

Russell Welch was not fooled. “From the very beginning, I have said that Reed was making stuff up,” Russell wrote me last year. “He was lying about Mena.” Russell had the details and the evidence on Reed.

Russell was the best kind of investigator—one who hates lies and is stubborn about the truth. He played by the book. It got him into trouble.

As the Arkansas State Police investigator based in Mena and tasked with monitoring Mena Airfield, Russell was assigned the Seal case around 1985, about the time one of Seal’s confederates was killed in a nearby plane crash. He quickly discovered that Seal had set up shop in Mena and was using the remote airfield as part of a smuggling network running cocaine from Colombia.

He also discovered that the Drug Enforcement Agency was already on to Seal. Seal had flipped and was cooperating with federal authorities.

Separately at Mena, and unconnected to Seal, other federal entities were running training exercises in the Ouachita Mountains and servicing aircraft used on clandestine missions at Mena Airfield. Judicial Watch disclosed last year that two of the federal entities were the CIA and the Defense Department.

“I did not want to investigate the Seal [case],” Russell wrote me. “I knew it was out of my league and the DEA should do the investigation.” But he was ordered to open a criminal investigation into Seal’s drug smuggling and money laundering.

“I started the criminal investigation,” Russell wrote. “I conducted it like any other investigation. I found that Seal had been [secretly] indicted in two different jurisdictions in Florida. He became a snitch for DEA Group 7 in Miami. His [immunity] period started in March of 1984. I knew that I had to keep my investigation focused on events prior to that. Anything that Seal…did after that date could have been part of a legitimate [DEA] investigation.”

Partnering with an IRS investigator, Bill Duncan, Russell compiled significant evidence of Seal’s drug smuggling and money laundering. “I did everything by the book,” Russell wrote. “When I finished the bulk of my investigation, there were no conspiracy theories floating around, yet. That started with Terry Reed.”

But the case developed by Russell and Bill Duncan went nowhere, killed by federal stonewalling and foot-dragging. A sinister conspiracy? Or something more mundane, like turf wars over witnesses and evidence? It was never entirely clear. But Russell and Bill persisted, and their careers suffered.

In 1986, Seal was murdered in Baton Rouge by Colombian gunmen. Later that year, a C-130 linked to Seal was shot down over Nicaragua with a load of guns for the Contra rebels, dragging a Mena interface into the Iran-Contra affair. In 1994, “Compromised” began to circulate, dragging the Clinton White House into the conspiracy.

Russell retired in 1996, but he never escaped the story. He was pursued by journalists, detectives, TV and documentary producers, authors promising book deals, conspiracy theorists, mooks, kooks, and menacers. For the most part, he kept silent, but he continued to work the case, taking notes, compiling evidence, documenting lies and discrepancies. He died in October, with his wife and his two sons at his side . He was 72. Let the record reflect that in addition to being a devoted husband and father and grandfather, Russell Franklin Welch loved to read and play the guitar, held a Master’s Degree in English, and served with distinction as an Army medic in the Vietnam War.

“The biggest regret in my life is not quitting law enforcement and spending more time with my children,” Russell wrote. “Seeing the hurt in their eyes, so many times, as I had to stop playing with them and go to work, was unbearable. Telling them that I would not be able to watch them at certain school functions, because I had to go to work, broke my heart. It still breaks my heart, and I think about it every day. While I was working on the Seal case, I was, also, conducting other investigations: murder, rape, robbery, and so on. I was busy all the time.”

That first day with Russell in Mena in the summer of 1994, we sat in the plastic chairs outside my motel room and talked a while. That case of anthrax that nearly killed him? The doctors never could figure out where it came from. One doctor had blurted out it was an infection caused by “military grade” anthrax, but Russell was cautious, not assigning blame, and later tests were inconclusive. Anthrax certainly caught the attention of Bartley at Journal, who brought it up with me many times over the years. And Russell had enemies. The Seal case. Murder, rape, robbery, and so on.

Later that day, we drove up into the Ouachita Mountains to take a look at one of Seal’s landing strips cut into the deep woods. I brought a metal detector, hoping to find some sort of journalistic treasure. Russell brought an AR-15 assault rifle. It crossed my mind that he could just shoot me and bury me in the mountains and be done with the troublesome Yankee. This was mysterious Mena, after all, and I was far from home. But you’ve got to know who to trust.

“Here,” Russell said, handing me the AR-15 and taking a camera from the trunk of the car, “let’s take a picture.”

I had a copy of that picture for years. So did Russell. That too is evidence.

***

Micah Morrison is chief investigative reporter for Judicial Watch. Follow him on Twitter @micah_morrison. Tips: mmorrison@judicialwatch.org

Investigative Bulletin is published by Judicial Watch. Reprints and media inquiries: jfarrell@judicialwatch.org

Reproduced with Permission.

Mara Leveritt has reported for almost three decades on police, courts and prisons. She is a past Arkansas Journalist of the Year, Laman fellow, and winner of the prestigious Porter Prize.

A contributing editor to the Arkansas Times, Mara has written four nonfiction books about crime and public corruption.

Leveritt's Reporting

May 21, 1992

Arkansas Times

Cover Story

Bad Company

By Mara Leveritt

Arkansas’s most notorious drug smuggler testified about his links to Colombia. His ties to Washington have yet to be explained.

State and federal officials monitored Seal’s activities almost from the day he moved his smuggling operation to this tiny airport at Mena.

It has been 10 years since cocaine smuggler Adler Berriman Seal moved his massive operation to Arkansas, and six years since Seal’s personal plane — the same one he used to run drugs — was shot down in Nicaragua, just months after Seal himself was murdered in Baton Rouge.

For years Seal had used his plane, which he based in Mena and affectionately called The Fat Lady, in the service of Colombian drug lords.

But when The Fat Lady went down in Nicaragua, she wasn’t carrying cocaine. She was loaded with military supplies for the Nicaraguan Contras. And the people paying for her flight were not Colombians; they were American covert operatives with direct ties to the office then-Vice President George Bush at the White House.

When U.S. officials embarked on their covert mission to assist the Contra rebels, they needed an up-and-running air cargo system; one that knew the routes between the U.S. and Central America, understood secrecy, and wasn’t averse to risk.

Such a system existed. It was made up of former U.S. military pilots and military and civilian intelligence agents, thousands of whom had been turned loose after the Vietnam war. They were, by and large, renegade adverturers; men like Barry Seal.

Their business was cargo — any cargo, to any destination. They worked for whoever paid. They developed ties with foreign drug lords and kept up ties with old buddies still in the U.S. government.

When Lt. Col. Oliver North began organizing the Contra shipments, he hooked up with this clandestine network. CIA chief William Casey recommended that North contact retired Army General Richard V. Secord, and it was Secord, acting as a for-hire contractor, who found pilots to make the secret air drops over Nicaragua. Such drops were a skill many pilots, including Seal, had already cultivated while making illegal drug flights into the United States.

The arrangement was an extremely compromising one; a situation that some officials here believe may explain the hands-off treatment accorded Seal during the years he operated in Arkansas.

***

While criticism has been leveled at Gov. Bill Clinton for his failure to adequately investigate Seal’s years at Mena, the more serious questions surrounding the case lead not to Little Rock, but Washington.

For instance:

- Seal’s smuggling activities, which were among the largest in the nation’s history, were known for years to federal agents. But he was never stopped. Why?

- When Arkansas officials tried to investigate Seal and bring the smuggler to justice, federal officials thwarted them at every turn. Why?

- Why, after Seal turned informant, did federal agents put him in a position where he was certain to be murdered? They knew his former associates had put out a contract on his life. Yet, though he refused protection, they ordered him disarmed and set free. He said he felt like a sitting duck, which he was.

- And why does the Bush administration to this day refuse to cooperate with investigators trying to probe the relationship between the White House, the CIA, and the Drug Enforcement Agency, and smuggler-operatives like Barry Seal?

***

In 1982, when police at the little town of Mena, on the Arkansas-Oklahoma border, learned that a major international drug smuggler was using the city’s airport, they called in the Arkansas State Police and other more experienced investigators.

But the case was strange from the start. For reasons that no one at the time could fathom, it seemed there were forces in the federal government that did not want this particular smuggler stopped.

Police knew they’d stumbled upon a large-scale operation.

What they didn’t realize until much, much later was that the pilot they suspected was slipping back and forth between Mena and Central America was also flying in and out of Washington, D.C.

Barry Seal could fly anything. In the mid-’50s, as a high school student in Louisiana, he flew an airplane to out-of-town games while his classmates rode the bus.

During the ’60s, Seal flew for the 20th Special Forces Group of the Army National Guard, an elite combat unit whose members are often used for covert operations.

By the early ’70s, Seal, now a civilian, was the youngest commercial 747 pilot in the country. He lost his premier spot with TWA in 1972 when federal authorities in Shreveport caught him loading a transport plane with almost seven tons of plastic explosives.

That’s where the pilot’s life — and his association with the federal government — takes a murky turn.

When the explosives case made it to court, the judge declared a mistrial because of unspecified “government misconduct.” A second trial was scheduled, but before it began, a second judge dismissed the charges against Seal entirely.

The explosives, it turned out, were destined for Cuba, where they were to be delivered to anti-Castro Cubans trained by the CIA. When asked about the circumstances of the case later, a federal prosecutor acknowledged they did seem to suggest that Seal might have been working on a government job, flying as an independent contractor.

His commercial career ruined by the episode, Seal switched to smuggling marijuana. He advanced quickly in the aviation underworld, to the point that he was soon working for the Colombian cocaine cartel, directly under its leader, Jorge Luis Ochoa. A confederate described Seal as something like a vice president of the cartel, in charge of transportation.