Jay Campbell

In the 1996 release of Pat Matrisciana’s documentary, “Obstruction of Justice: The Mena Connection,” Linda and Jean name Jay Campbell and Kirk Lane as suspects in the murders of Kevin and Don. Campbell and Lane sued Matrisciana for defamation. They won at trial, but the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the jury verdict because the trial judge withheld evidence that incriminated Campbell and Lane.

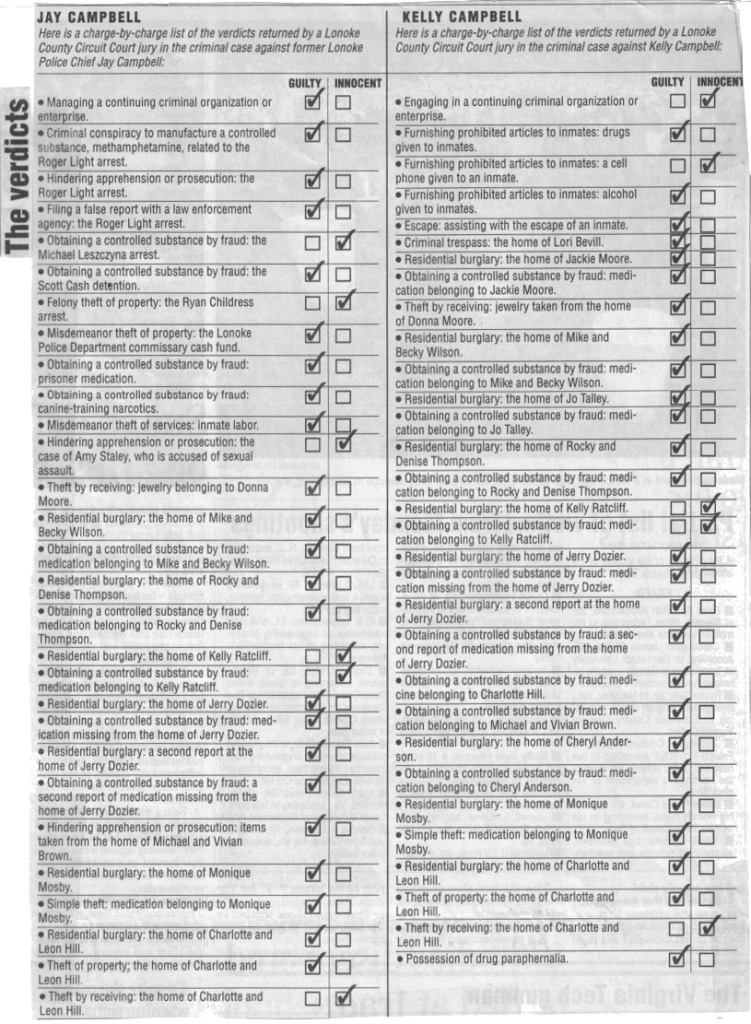

There were FBI agents, and other law enforcement officers who testified as character witnesses at the trial. The jurors surely couldn’t help but to be impressed with the clean-cut, sharp-dressed, articulate officers, sworn to protect and serve, as one by one they were sworn in and took the stand. One has to wonder just how well they knew Campbell, and just how foolish they must have felt when a decade later, Campbell’s true character was revealed when, as Lonoke Police Chief, he was convicted of running a criminal enterprise for years and sentenced to 40 years. The tally sheet below shows the crimes for which he was found guilty. His wife, Kelly Campbell, was his partner in crime, and her tally sheet is beside his.

As it goes in Arkansas, the Supreme Court reversed Campbell’s conviction on the criminal enterprise charge (the charge that carried the longest sentence and all the other sentences ran concurrently) because – are you ready for this? – lurid trial testimony that Campbell’s wife had sex with state prisoners at the local jail kept him from receiving a fair trial.

He’s the one who pimped her out! Of course it was prejudicial. It was part of his criminal enterprise. Typical Arkansas Justice. See AP article.

The Verdicts

Couple Charged With Multiple Felonies

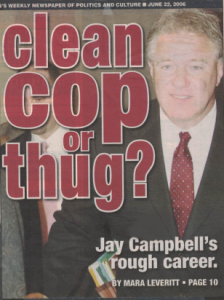

June 22, 2006

Arkansas Times

A big cop’s reputation takes another hit with charges of sex, drugs and thievery.

By Mara Leveritt

No cop wants to arrest a fellow officer. But when Lonoke County Sheriff Jim G. Roberson served Lonoke Police Chief Ronald Jay Campbell with a warrant, it didn’t break Roberson’s heart.

No cop wants to arrest a fellow officer. But when Lonoke County Sheriff Jim G. Roberson served Lonoke Police Chief Ronald Jay Campbell with a warrant, it didn’t break Roberson’s heart.

“I thought he was a one-dollar millionaire,” Roberson observed recently in his office near the Lonoke County Courthouse. “You know how some people try to present themselves as something they’re not?”

The city police department, which Campbell headed for two and a half years, stands a mere five blocks from Roberson’s sheriff’s office. Between the buildings, street banners advertise “Lonoke. Life as it should be.

But recent filings at the courthouse suggest not all has been ideal.

In early February, Lonoke County Prosecuting Attorney Lona Horne McCastlain charged Campbell, a former Pulaski County narcotics officer, with a slew of felonies. They included manufacturing methamphetamine, hindering prosecution, burglary and theft.

Campbell’s wife, Kelly Campbell, was charged with burglary and theft too, as well as with taking inmates from the city jail for sex and providing them with drugs and alcohol.

Campbell’s wife, Kelly Campbell, was charged with burglary and theft too, as well as with taking inmates from the city jail for sex and providing them with drugs and alcohol.

Campbell resigned as Lonoke police chief on Feb. 8. Free on bond, he and his wife have pleaded not guilty to the charges. A preliminary hearing in their case is scheduled for this week.

Last spring, it fell to Sheriff Roberson and Charles McLemore, a criminal investigator for the Arkansas State Police, to serve warrants on the pair.

“We did it by phone,” Roberson said, “just to save them embarrassment. I called Jay and told him they had to come and see me.”

Roberson doubts his call came as a surprise.

“They had already been interviewed by the State Police, so I think they knew what was coming,” the sheriff said. “But he acted as if he didn’t believe it. He acted like I was joking.”

Since then, prosecutors and Campbell’s attorneys have agreed to divide the case into two trials. At one, Campbell and two Little Rock bail bondsmen will be tried on the methamphetamine-related charges. The other trial will deal with the remaining charges that Campbell faces with his wife, Kelly.

Since then, prosecutors and Campbell’s attorneys have agreed to divide the case into two trials. At one, Campbell and two Little Rock bail bondsmen will be tried on the methamphetamine-related charges. The other trial will deal with the remaining charges that Campbell faces with his wife, Kelly.

As of this writing, almost four months after the arrests, no trial date has been set. When the cases do go to trial, they may shed a bit more light on Campbell’s 25-year career, much of it spent in the shadowy world of narcotics law enforcement.

Most people who have known Campbell describe him as likeable: a gregarious, back-slapping guy. He’s a big fellow, they often note: 6-foot-3 and weighing about 280 pounds.

He was big even in 1981, when he joined the Pulaski County Sheriff’s Office at the age of 20. By 1987, Campbell had risen to the rank of sergeant over the narcotics division. Officers who worked with him on drug arrests say he won their respect.

Robert Govar, a deputy U.S. attorney who prosecuted some of those cases, held Campbell in high regard.

“I thought he was an excellent drug investigator,” Govar said. “He’s done some good work. In fact, he helped on the case of Troy Warner, the first dealer we tried who was found with a fully automatic 30-caliber machine gun.”

Warner’s 1988 trial reverberated through Central Arkansas, in part due to allegations by Warner’s attorney, R. David Lewis, that Campbell and other deputies had used excessive force during their investigation.

One witness claimed that Campbell had beaten him. Another claimed that Pulaski County Sheriff’s Deputy Kirk Lane had planted drugs on him.

Arguing that Campbell and Lane had spawned a wave of “terrorism,” Lewis took affidavits to the Pulaski County sheriff, the Arkansas State Police and the FBI, seeking an investigation into the deputies’ activities, but his appeals were dismissed.

Lane, a former Benton police officer, joined the Pulaski County Sheriff’s Office in the mid-1980s, joining his friend Campbell. Lane remains there, working as a captain over investigations.

But that office — indeed, much of Central Arkansas — was a different place in the mid-1980s, when Lane and Campbell worked narcotics together. The undercover world they inhabited seemed for a time exceptionally rife with corruption and violence.

In one infamous case, just a year before Warner’s trial, two Saline County teen-agers, Don Henry and Kevin Ives, were found murdered on a railroad track near the Pulaski-Saline county line. Some kind of drug connection was suspected.

Arkansas Circuit Judge John Cole, a veteran of Saline County politics, appointed Benton attorney Dan Harmon to conduct a special grand jury investigation into circumstances surrounding the deaths. Harmon’s probe went on for months.

Linda Ives, mother of one of the boys, claims that in the midst of it, in August 1988, Harmon told her that the men he had scheduled to testify the next day were those responsible for her son’s murder. The following day Harmon questioned Campbell and Lane.

The deputies, along with their boss, Maj. Larry Dill, made no secret of their contempt for Harmon and their resentment at being called. Dill derided the proceedings as Harmon’s “dog-and-pony show.”

But the display left reporters and other observers baffled. Why would Harmon, the anti-drug crusader from Saline County, and the narcotics detectives from Pulaski County, be at such visible odds?

Only gradually, over time, has part of the explanation emerged.

One piece, it turned out, was that Harmon was not just prosecuting drug offenders. He was a drug offender himself.

In 1997, almost a decade after the train-deaths grand jury, Harmon would be convicted in federal court of extortion and of using his office for drug racketeering. But that was not known at the time.

Nor was it publicly known that, at the time of Harmon’s much publicized grand jury, Dill, Lane and Campbell were part of a joint drug task force that had the special prosecutor under investigation.

Years later, when I interviewed Campbell for my book “The Boys on the Tracks,” he told me, “My personal opinion was that Harmon used that grand jury to find out what he could about who had information on him, and to make it appear like we were suspects.”

He continued: “I believe he called us blatantly, for the sole purpose of trying to discredit us, so that in case he got arrested and charged with drugs as a result of the federal investigation, he could say it was retaliation.”

Harmon’s lengthy investigation into the train-deaths case resulted in nothing. No one was ever charged with the murders. Though members of the grand jury prepared a five-page report, Judge Cole ordered that it not be released.

Cole then praised the fruitless exercise.

“I think if we’ve accomplished nothing else,” he said, “we’ve at least caused the citizens of this county to know that there is a body, there is a way, there are people with dedication, there are people with perseverance who will do everything humanly possible and within the law to see that the administration of justice in this county is served.”

But Harmon’s grand jury investigation was not the only thing that took a dive. The drug task force investigation of Harmon, in which Campbell and Lane were involved, also came to naught.

In fact, in June 1991 — three years after Harmon called Campbell and Lane to appear before his grand jury and six years before Harmon was finally convicted for drug racketeering — Chuck Banks, the U.S. attorney at the time, called a press conference specifically to refute reports that investigators had found any evidence linking Harmon to drugs.

“Quite frankly,” Banks said, “there is none. We found no evidence of any drug-related misconduct by public officials in Saline County.”

Skeptics, including Linda Ives, were left believing that no one involved in drug investigations in Central Arkansas could be trusted. Her sense of betrayal intensified as Harmon’s unchecked conduct grew increasingly erratic. Slowly, others came to share her opinion — to the point that, about a year before Harmon’s arrest, an Arkansas Times profile of him was headlined: “Out of Control in Saline County.”

The mistrust Ives had developed extended to Campbell and Lane, as well.

In the years after the grand jury, as Ives sorted through police records on various failed investigations into her son’s murder, she had come across police files that seemed to her to support Harmon’s suggestion that they were her son’s killers.

She had seen, for instance, the report of an interview that FBI agents had conducted with Dan Lasater, a Little Rock bond dealer, after his arrest in 1986 for distributing cocaine. According to the FBI report, Lasater said he’d known he was being watched by federal agents because he had been tipped off by Campbell.

Ives suspected that Campbell was crooked, and reports she found in the Arkansas State Police file strengthened that view.

In one interview, conducted a year after the murders, a man named Ronnie Godwin told State Police investigators that, on the night of the deaths, he’d seen two men, whom he believed to be police officers, near a phone booth at a grocery store in the vicinity of the tracks. With the men were two teen-aged boys. He said he first thought the cops had caught the boys stealing from the store.

But then, Godwin reported, he saw the larger of the two men push one of the boys against the phone booth. The other man stood over the second boy, who was kneeling on the ground “with his head down.”

Ives learned that Godwin had given a similar statement to Saline County Deputy Prosecutor Richard Garrett. According to Garrett’s report, Godwin said: “I could not tell much about the officers except the one pushing the subject against the phone booth, and he was about 200 pounds, six foot tall, with sort of long brown hair …

“As I stopped my car, I saw them pick the boy up off the ground and throw him into the back seat.” According to Godwin, the car had police hubcaps, three antennas on the trunk and a spotlight on the side.

Another report Ives discovered in the file seemed to corroborate Godwin’s account. This was of an interview conducted in 1990 — three years after the murders — with a nightclub owner named Mike Crook. Nothing in the file suggested that Crook was aware of Godwin’s statements.

Crook told police that on the morning the boys’ bodies were found, a man he knew only as Jerry had come into his club, claiming to have seen the boys the night before, smoking a joint at the Ranchette Grocery Store.

According to Crook, Jerry said he saw two men in plain clothes pull up in an unmarked police car. Jerry identified one of the men as Lane, whom he’d known from the Benton Police Department. He said the other man, whom he did not know, was larger.

The interview noted: “Crook states that the boys and these two cops got into an argument and the two cops beat the boys unconscious and threw them into the car and then drove off.”

Crook also told the State Police investigator that the manager of another bar, who was himself murdered shortly after the train deaths, had told friends that he feared Campbell and Lane. The interview noted:

“Crook states that before Keith McKaskle was killed, McKaskle told him that Kirk Lane and Jay Campbell of the Pulaski County Sheriff’s Office were following him around and he was afraid they were going to kill him.”

Ives believed the accounts. When California filmmaker Pat Matrisciana sought her help in making a documentary video about the case, she agreed.

Matrisciana’s film, titled “Obstruction of Justice: The Mena Connection,” examined the still-unsolved murders of Don Henry, Kevin Ives, and Keith McKaskle, along with some of what was known about corruption at the time in Saline County.

It ended with a screen that read: “Suspects Implicated in Ives/Henry Murders and Cover-Up.” Beneath that headline ran the names of six people, all related to law enforcement. Campbell and Lane’s names were among them.

The two Pulaski County deputies sued Matrisciana for libel in federal court. When the case went to trial, in August 1999, the deputies’ attorneys called a couple of journalists, including me, as witnesses on their behalf.

I testified, for example, that I had by then written a book about the Henry/Ives case that included Godwin and Crook’s statements. But I did not claim, as had Matrisciana’s film, that Campbell and Lane were “implicated” in the murders.

The pair’s lawyers also called a parade of law enforcement officers — particularly from the FBI — to attest to their clients’ professionalism and good character.

Mike Smith, supervisor of the FBI’s organized crime and drug program in Little Rock, described Campbell as “completely dependable,” a man with “a lot of street savvy,” and a friend.

Another Little Rock FBI agent, Brian Marshall, described Lane and Campbell both as “very competent law enforcement officers” and of the “highest character.”

James Handley Jr., a former FBI agent who, at the time, worked as head of security at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, said he had never known Campbell to be “anything but honest and forthright.”

Richard Stephen Holland, a former Benton police officer, called Campbell “a fine fellow” who “believes in law enforcement.”

Sheriff Donny Ford, of Dallas County, rated Campbell “among the top” law enforcement officers he knew, adding: “I’ve trusted him with my life.”

On a more personal note, Campbell’s older brother, Steven G. “Pete” Campbell, testified that the video had harmed his brother by dashing his hopes to run for sheriff of Garland County. Pete Campbell told the court that the video’s claims had made it hard to raise funds for a campaign.

When Campbell himself took the stand, he testified that, at the time of the Ives/Henry murders, he was working as a sergeant over the Pulaski County narcotics division.

He discounted Crook and Godwin as unreliable sources, noted that police investigative files often contain unfounded statements, and complained that Matriciana had never contacted him to get his side of the story.

“As an officer as well as a person,” Campbell said, “I was raised that a handshake was a contract. Your word was something that you lived by.” He said release of the video had left him with no opportunity to clear his name.

Little Rock attorney John Wesley Hall represented Matriciana. He began his questioning of Campbell with an air of familiarity.

Little Rock attorney John Wesley Hall represented Matriciana. He began his questioning of Campbell with an air of familiarity.

“I guess it’s fair to say we’ve been professional adversaries for a long time?” Hall asked Campbell.

“Almost 18 years, sir,” Campbell agreed.

“I’ve had cases where I’ve actually accused you guys of throwing down [planting] drugs in cases,” Hall said.

“Yes, sir. You certainly have.”

Throughout the trial, Hall tried to establish that police officers are often maligned, that the First Amendment protects citizens’ rights to voice suspicions about public officials, and that police officers do not go to court claiming they’ve been defamed every time such an unpleasant thing happens.

But the jury concluded that Campbell and Lane had been right to bring their case to court. It awarded them a total of $598,750 in damages.

During the trial, Ives had wondered why Campbell’s co-workers — his fellow Pulaski County deputies — were not called as character witnesses. Five months after Campbell’s successful libel trial, she believed she understood the reason.

In February 2000, Pulaski County Sheriff Randy Johnson fired Campbell. Johnson outlined his reasons in a letter to Campbell that was supplied to the media. The letter claimed that Campbell had bullied subordinates, using “intimidation” and the authority of his rank, to pressure them not to take part-time jobs for less than what Campbell wanted employers to pay.

In addition, Johnson wrote, Campbell had created a “blackball” list of deputies who had not submitted to Campbell’s demands. Johnson wrote that Campbell had then circulated the list in a memo.

Campbell sued Johnson over the firing, but this time, he lost. And soon after that, he suffered another legal blow.

Matrisciana, the filmmaker, had appealed the Little Rock jury’s verdict. And in January 2001, almost a year after Campbell was fired, the U.S. Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals sided with Matrisciana.

The appellate court’s opinion began: “The record in this case reads like a John Grisham novel.”

Twenty-one pages later, after a review of the trial testimony, the appellate court concluded: “All in all, statements and rumors corroborating the Lane-Campbell scenario or implicating them as suspects emanate, in varying degrees of detail, from multiple sources.”

The opinion continued: “Viewing each statement in isolation, there may have been reasons to doubt the veracity of Godwin, Crook, or Harmon. However, given the corroboration by multiple sources, we do not see obvious reasons to doubt the accuracy of the various reports.”

Finally, the justices noted: “While we are not aficionados of conspiracy theories, we suppose that if Matrisciana’s assertions were true, there would be ‘inherent difficulties in verifying or refuting’ such a claim, given the alleged pervasive involvement of law enforcement in his theory.”

Campbell was now out the $309,750 he had expected to receive in damages, and also out of a job. He rebounded by starting a detective agency in Lonoke called Investigative Consultants. That led to his hiring in 2003 as the city’s chief of police.

That began Sheriff Roberson’s acquaintance with Campbell.

“I started out thinking our people would work together,” the sheriff said of the city police chief. “I soon found out that that wasn’t the case.”

When it came to working drug cases, Roberson said, “I found out that that if we were out in the county, they liked working with us, but they didn’t want us joining them in the city.”

The sheriff added, “And my narcotics officer — he wants everything right or he won’t do it, he won’t violate a subject’s Fourth Amendment rights — he didn’t like the way they did business.”

Within two years, Campbell, the private investigator turned police chief, was under investigation himself.

State police investigator Charles McLemore, of Company B in Pine Bluff, was asked to check out allegations that certain inmates from the Arkansas Department of Correction, who’d been loaned to the city of Lonoke, were not being properly managed.

Under Arkansas Act 309, hundreds of inmates are allowed to work for other public agencies while being housed in local jails. The plan is to help communities, while also relieving crowding in the state penitentiaries.

McLemore interviewed inmates who had been to Lonoke. He would later write:

“During the course of this investigation, numerous irregularities were divulged by prisoners. Those irregularities included drug use, sex, and personal use of prisoners to perform personal services for various individuals.”

According to McLemore, inmates reported fixing an air-conditioner for Mayor Thomas Privett, hanging Christmas lights on Privett’s house, working in the mayor’s garden and repairing his porch.

They also reported working for Campbell.

“The prisoners disclosed that they had put in a sidewalk at the chief’s house that went to the swimming pool,” McLemore wrote.

“The prisoners also refurbished the chief’s party barge and took a motor off an old boat and put [it] on the party barge. This work was done in the old Otasco building owned by Mayor Thomas Privett.”

McLemore noted that both Campbell and Privett had admitted that the services were performed, “but claimed that the prisoners had been paid by the city.”

By then, however, other issues loomed larger.

“Prisoner Andrew Baker disclosed that Chief Jay Campbell’s wife had a very close relationship with at least two of the 309s,” McLemore wrote. “Baker disclosed that the chief’s wife, Kelly Campbell, had brought a fifth of vodka, a fifth of gin, and a fifth of Crown Royal and other bottles of unknown alcoholic substance to the jail and given it to the 309s that wanted it.”

Baker also reported that Kelly Campbell had:

• brought marijuana into the jail for prisoners;

• given one prisoner a cell phone, which they “used to communicate with each other regularly;”

• allowed photos of herself to be taken “in various intimate poses” inside the old Otasco building, while inmates were working on the party barge;

• had sex with inmates “eighteen to twenty times” in various places in and around Lonoke, including the Holiday Inn Express, the press box at the ballpark, the Campbells’ home on Cherry Street, and the chief’s office at the Lonoke Police Department;

• and paid one inmate $260 “to keep his mouth shut.”

Officers at the police department reportedly “confirmed that the chief’s wife was having a relationship with the 309s and was coming and going freely from the jail.”

According to McLemore, they said:

• that they could not keep the chief’s wife out of the jail;

• that when they tried, “she became irate;”

• that “when they tried to discuss it with the chief, he would not discuss it;”

• and that when Campbell learned that dispatchers were documenting his wife’s comings and goings in the jail log, “he became irate.”

Nor did the reports McLemore was hearing stop with sex.

“During an interview with another witness involved in this case,” he wrote, “several names of potential victims of theft were given to me.”

McLemore outlined statements from four Lonoke County residents, all of whom reportedly said that, after visits from one or both of the Campbells, they had found prescription narcotics missing.

Kelly Ratcliff was one of the four. She reported that, following surgery in 2004, she’d been prescribed the drug Mepergan for pain. According to McLemore:

“Ratcliff put the medicine beside her on the computer desk in the bedroom. Kelly Campbell brought food over to the house shortly after her arrival home from the hospital. Kelly Campbell stayed for about 10 minutes.

“The medication was there prior to Campbell coming to the house and was missing after Campbell left. That night Kelly Ratcliff began to hurt and called Kelly Campbell, who brought Ratcliff two pills from Ratcliff’s prescription.”

Then there was the jewelry.

McLemore heard that, at one point, “Kelly Campbell had pawned a lot of jewelry in Little Rock and returned with approximately $7,000 in 100-dollar bills.”

He turned to l.e.a.d.s.online, a website that allows criminal investigators to access transactions from participating pawn shops.

Several police agencies in Arkansas use the l.e.a.d.s.online system, and, according to an official of the Arkansas Pawnbrokers Association, Jay Campbell “was well aware” of the database “because he was a Pulaski County officer when Pulaski County was looking into buying in.”

McLemore traced a couple of transactions made by Kelly Harrison Campbell. One was at a Little Rock pawnshop called Pacer Ltd.

Tim Collier, one of Pacer’s owners, told McLemore that he was raised in Hot Springs, where Jay Campbell grew up, and that he’d known him since the fifth grade.

Collier told the investigator that in late June 2005, Jay Campbell had come to the shop saying his wife had inherited some antique jewelry, which he wanted to leave at the shop on consignment.

Collier had made photocopies of the jewelry and of Kelly Campbell’s driver’s license, which he turned over to McLemore.

Collier said he sold the jewelry and paid Campbell $4,000. However, according to McLemore, “a few days later, on a Sunday morning, Jay Campbell called Collier’s cell phone panicked, saying that he had to get the jewelry back.

“Jay Campbell gave Collier two or three different stories about why he had to have the jewelry back.

“Collier related that he had to go to three different customers to get the jewelry back, but that he was able to get all of it back with the exception of a pair of earrings. He told Jay Campbell who had these earrings, and Jay Campbell obtained those himself.”

The investigator then spoke with some neighbors of the Campbells, Leon Hill and his wife, who had reportedly had some jewelry stolen. McLemore wrote:

“The Hills were shown a picture of the jewelry and asked if they recognized it. Mrs. Hill stated that the photocopied pictures were photos of her jewelry.

“She then related that on July 9, 2005, she was getting ready to go to a friend’s birthday party in Little Rock, when she realized that her jewelry was missing … Mrs. Hill related that she was extremely upset and sick that her old wedding band and other jewelry were missing.

“The next day, Mrs. Hill approached Jay Campbell and informed him that she would get her jewelry back even if she had to go to the Arkansas State Police or higher ups.

“A few days later, Jay Campbell brought her jewelry back to her with a story about how his brother had come to visit him and taken the key that he and Kelly Campbell kept to the Hill home and made a copy and then came in and took the Hills’ jewelry. …

“Mrs. Hill demanded her two keys back from Jay Campbell and had her locks changed.”

Disturbing in another way were allegations that Campbell had abused his police authority, particularly his power to arrest.

According to the warrant filed at his own arrest, Campbell conspired with Little Rock bail bondsman Bobby Cox to have an intermediary persuade a man named Roger Light to cook a batch of methamphetamine, so that Light could be arrested.

The idea, according to the warrant, was that Campbell and Cox could then “force” Light to help them catch an unnamed fugitive who had jumped a substantial bond underwritten by Cox.

The intermediary who set up Light expected that, in return, Campbell would help him clear his own record. He reported, however, that when he asked for their assistance, Cox threatened him and Campbell “told him he got screwed.”

As a result of that exchange, the intermediary reportedly decided he had nothing to lose by spilling his story to the State Police.

By February, when Sheriff Roberson called the Campbells to his office, the situation was clearly no joking matter.

Campbell stood accused of multiple felonies, including conspiracy to manufacture methamphetamine, hindering apprehension or prosecution, criminal conspiracy to commit residential burglary, theft by receiving and theft of services.

His wife, the mayor and two bail bondsmen faced numerous related charges.

And this time, when Campbell heads to court, the national media will be watching.

Some of the faces expected to appear are likely to be familiar.

Some of the faces expected to appear are likely to be familiar.

Immediately after Campbell’s arrest, Linda Ives wrote letters reminding Lonoke officials that she had tried to warn them about Campbell when he was hired as the city’s police chief.

John Wesley Hall, who beat back Campbell’s libel lawsuit for filmmaker Pat Matrisciana, has been hired this time around to represent Campbell’s co-defendant, Bobby Cox.

Campbell himself will be represented by Hall’s partner, Patrick Benca.

Coming out of retirement to preside over the trials is Judge John Cole of Saline County.