| Thursday,

September 28, 2017 Arkansas Times Cover Story |

|

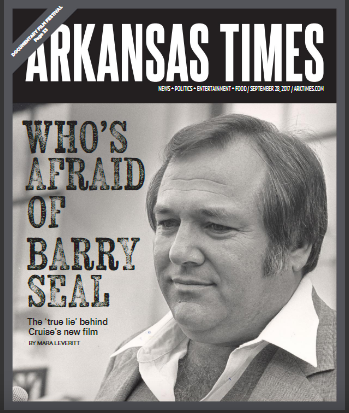

Who’s Afraid of Barry Seal?

| The 'true lie' behind Tom Cruise's new film on the notorious drug-trafficker-turned-federal-informant who operated out of Arkansas. |

| BARRY SEAL: He imported drugs and laundered money while working for the federal government. |

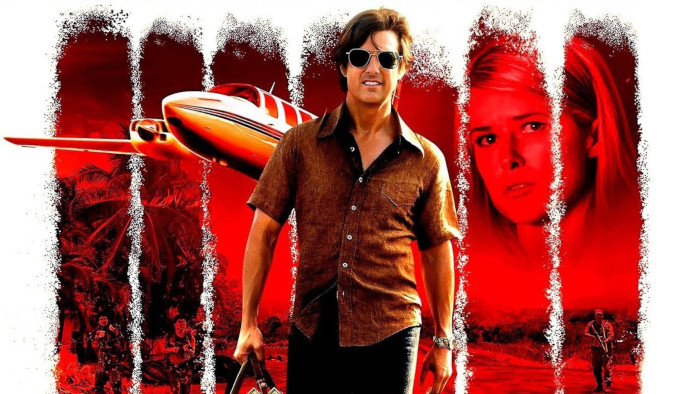

The poster for the movie “American Made,” to be released Friday, Sept. 29, shows a grinning, cocky Tom Cruise as the drug smuggler Barry Seal, hauling a duffle bag bursting with cash. “It’s not a felony if you’re doing it for the good guys,” the poster teases. The film’s trailer has Seal casually boasting about his simultaneous work for “the CIA, the DEA and Pablo Escobar.”

One critic was led to ask: “So, was Seal a triple agent?” Perhaps. The producers say this swaggering story, based mostly in Arkansas, is all “based on a true lie.”

“American Made” is Hollywood’s second film about Seal, the trafficker-turned-government-informant who is fast becoming America’s most intriguing outlaw. HBO released the first, “Doublecrossed,” starring Dennis Hopper as Seal, in 1991, five years after Seal’s controversial murder.

When Cruise’s film was announced, its title was going to be “Mena,” after the town in Arkansas where a local company hid Seal’s aircraft and modified them for drug drops. I was a reporter focusing on drugs in the 1980s, but I learned of Seal’s three-year presence at Mena only after the night in 1986 when Colombian assassins gunned him down in Baton Rouge, La.

I became one of many reporters who tried to untangle Seal’s story and, though that task ultimately proved impossible, I did learn a lot about him. But now, the bits and pieces collected about Seal have provided enough material — enough “true lies” — for Hollywood to weave into films that enlarge his legend.

But his actual story is littered with dead ends — secrets that are still being carefully kept — especially in Arkansas. And here, I’m sorry to say, some police records that were open to the public 20 years ago are apparently no longer available.

I wouldn’t know this if it weren’t for Cruise’s film. When it was announced with a planned release in 2016, Rod Lorenzen, the manager of Butler Center Books, a division of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, asked me to write a history of Seal’s time in Arkansas to correspond with the movie’s release. I was honored. The Butler Center is part of the highly respected Arkansas Studies Institute, a creation of the Central Arkansas Library System and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

I’m a huge admirer of the ASI and consider its staff my friends. Yet I declined. I told Lorenzen that the book he proposed would be too hard to write; that there were still too many people in power — in both political parties — who did not want Seal’s full story told.

But Lorenzen persisted. I began to waver, recalling the words of some Arkansans who’d known Barry Seal.

“I can arrest an old hillbilly out here with a pound of marijuana and a local judge and jury would send him to the penitentiary,” a former sheriff at Mena in 1988 had said, “but a guy like Seal flies in and out with hundreds of pounds of cocaine and he stays free.”

The prosecuting attorney there had avowed: “I believe that the activities of Mr. Seal came to be so valuable to the Reagan White House and so sensitive that no information concerning Seal’s activities could be released to the public. The ultimate result was that not only Seal but all of his confederates and all of those who worked with or assisted him in illicit drug traffic were protected by the government.”

And this, by the Internal Revenue Service agent who’d found evidence of money laundering at Mena: “There was a cover-up.”

Nothing had changed with regard to Seal since those men spoke those words, except that the savage war on drugs had ground on, while Seal — whatever he was — remained a hidden but important part of its history. Finally, I told Lorenzen I would write the book; I would document as much as I could of Seal’s secretive Arkansas years.

We agreed that the book would be called “The Mena File: Barry Seal’s Ties to Drug Lords and U.S. Officials.” Lorenzen commissioned a cover while I began my research by contacting the Arkansas State Police. I knew the agency had an extensive file on Seal because I’d read it decades earlier, shortly after Seal’s murder. In fact, I still had a letter from the former director advising me, in case I’d planned to make copies, that the file held some 3,000 pages.

But now, three decades after Seal’s murder, State Police spokesman Bill Sadler reported that he could locate no files on Seal. None. Arkansas’s Freedom of Information Act requires the release of public records, but Sadler said that, in Seal’s case, the agency was unable to do that. I protested, and after weeks of back-and-forth, Sadler reported that a file on Seal had been discovered. He eventually provided a packet of 409 pages. He said this was all the agency could release after duplicates and documents that are exempt from public disclosure were removed.

Even allowing for duplicates and legal exemptions, I would find the reduction of publicly available records, from 3,000 pages 20 years ago to just over 400 now, disturbing. My concern increases when the case is one of national interest that’s also replete with political connections. As Sadler suggested, the state police in the past may have made too much available. On the other hand, if the grip on information about Seal has been tightened, the reason for this extra control might be traced to his earliest days in Arkansas.

By late 1982, when Seal moved his aircraft to Mena from his home base in Baton Rouge, federal agents had already identified him as “a major international narcotics trafficker.” Police watching Mena’s airport notified federal authorities that a fat man from Louisiana had begun frequenting an aircraft modification company there called Rich Mountain Aviation.

That same year, President Ronald Reagan appointed Asa Hutchinson, already a tough, anti-drug crusader, as U.S. attorney for the Western District of Arkansas. Wanting to keep tabs on Seal, Hutchinson ordered William Duncan, an investigator for the IRS, to watch for signs of money laundering around Mena resulting from Seal’s presence.

Another investigator, Russell Welch of the State Police, was assigned to look for evidence of cocaine arriving there. Duncan and Welch both told me that being assigned to Seal ended up ruining their careers.

Welch said he began to suspect that something was amiss one night in December 1983, when he and several other law enforcement officers had staked out the airport, watching for Seal. He said they’d seen the smuggler and his co-pilot land and taxi to a hangar at Rich Mountain Aviation, where workers installed an illegal, extra fuel tank in the plane.

Welch said that Seal had taken off into the wintry night, fast and without lights. But what he remembered most was how surprised he, the FBI agents and the Arkansas Game and Fish officer who’d joined them had been that, although officers for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration had met them at a motel in Mena, none had gone with them to the stakeout.

| THE FAT MAN AND THE FAT LADY: Seal and his C-123 airplane, both nicknamed for their girth. |

Seal had no criminal convictions at the time, but he did have a puzzling record. Ten years earlier, federal agents in Louisiana had caught him attempting to take off from an airport in Shreveport with a planeload of plastic explosives bound for Cuban ex-patriots in Mexico. Seal was charged with being part of a plot to overthrow Fidel Castro. But prosecutors abruptly dropped the case at the start of his trial. That event, relatively early in Seal’s career, would later prompt speculation — unquestioned in Cruise’s film — that he performed contract work for the Central Intelligence Agency.

From later court records, we know that in April 1981, before Seal moved to Mena, DEA agents in Florida had caught him in a drug sting. We know that while his case there was pending, Seal agreed to become an informant for the DEA — but that the circumstances of that deal were also strange. In the summer of 1984, facing possible life in prison if convicted, he’d flown his Lear jet to Washington, D.C., where, in a meeting with top DEA officials, he’d established the terms that would allow him to remain free.

Duncan and Welch were not informed of Seal’s change of status as they pursued their respective investigations. Throughout 1984, they had no idea that Seal was supposedly working for an agency of the U.S. Department of Justice. So far as they could tell, he was a drug-runner continuing to run drugs, while the DEA remained, as both officers put it, “conspicuously absent” from Mena. The Arkansas lawmen, along with their peers in Louisiana, could scarcely have imagined all that Seal was up to that year.

From a variety of surviving court records, we know that DEA officials in Florida cooked up a plan for him to help them round up the leaders of Colombia’s Medellín cartel in one dramatic sting. Suffice it to say that the plan turned into a catastrophic failure — one that exposed Seal’s status as an informant to his former associates in the cartel.

With Seal’s usefulness in that regard ended, he was put to another use. This time it was a political one — on behalf of Reagan’s White House. Reagan wanted evidence that officials of Nicaragua’s Sandinista government, which he opposed, were shipping cocaine into the U.S. After allowing CIA technicians to install hidden cameras in his C-123, Seal flew to Nicaragua and returned with photographs that he said showed Sandinista leaders helping load cocaine onto the plane.

But again, Seal was compromised. Someone who knew of the flight leaked word of it to a Washington newspaper. Seal’s status as an informant was confirmed, placing his life at still greater risk.

After that, the justice department found yet another use for Seal, as U.S. attorneys began calling him to testify about his experiences with major drug dealers whom they were prosecuting. From Seal’s testimony at some of those traffickers’ trials, we know that he claimed to have grossed $750,000 per flight while he was smuggling for the cartel; that he continued to fly in drugs after becoming an informant; that he had smuggled about 6,000 pounds of cocaine into the U.S. during that period; and that for one of those flights alone the DEA had allowed him to keep the $575,000 he’d been paid.

But it’s clear that by late 1984, Seal was getting worried. A man who had lived by secrets suddenly made the unthinkable move of agreeing to be interviewed by a reporter. Seal flew Louisiana TV reporter Jack Camp to Mena, where he allowed Camp to film him inside the C-123 as he talked about his work for the DEA, while pointing out the places where the CIA technicians had hidden their cameras.

It was only after Camp’s interview aired on Baton Rouge television in late 1984 that law enforcement in Louisiana — and, quickly enough, Arkansas — accidentally learned of Seal’s dual roles. But even now his status remained unclear, and federal officials weren’t trying to help. Seal was still flying, apparently free, in both states, while ground crews, including workers at Rich Mountain Aviation, continued to work with him. Duncan and Welch focused their own investigations on the period before Seal became an informant.

In mid-1985, Duncan told Hutchinson that he had sworn statements from employees at Rich Mountain Aviation and Mena bankers about illegal cash deposits being made into area banks. With what he called this “direct evidence of money laundering,” Duncan asked Hutchinson to subpoena 20 witnesses, all of whom, he said, were ready to testify before a federal grand jury. But Duncan said that Hutchinson balked and, in contrast to his conduct in other cases where Duncan had requested subpoenas, in this case the U.S. attorney subpoenaed only three. Later, when Duncan was asked under oath in a deposition whether he believed there was a cover-up, he replied, “It was covered up.”

In August 1985, shortly after Duncan’s request for subpoenas, U.S. Attorney General Edwin Meese flew to Fort Smith to meet with Hutchinson. DEA Administrator John C. Lawn was with him. While the nation’s two drug officials were in town, they held a press conference with Hutchinson to announce a series of raids dubbed “Operation Delta-9,” which they said were meant to eradicate home-grown marijuana. Although Fort Smith sits just 70 miles north of Mena, nobody mentioned Seal. No one even mentioned cocaine.

By then, though local investigators still did not know it, Seal had become a darling of the Department of Justice. In October 1985, the President’s Commission on Organized Crime invited him to be the featured speaker at a symposium in the capital attended by several top U.S. law enforcement officers. The following month Hutchinson announced that, having decided to run for Congress, he would be resigning as U.S. attorney.

At first, it looked like Hutchinson’s successor, J. Michael Fitzhugh, was ready to act on the cases related to Seal. In December 1985, Fitzhugh announced that he had subpoenaed Seal to testify at a grand jury session to be held in Hot Springs. In preparation, he sent Duncan to Baton Rouge to interview Seal, and the State Police sent Welch.

When I interviewed the investigators for my book, they told me that Seal seemed weary. He and his attorney fretted that Seal’s deals from Florida would not protect him in Arkansas. But, after some dickering, Seal agreed to be sworn in. “I don’t want to waste these men’s time,” he told his attorney, Lewis Unglesby. “They have come a long way in bad weather and it’s Christmas.”

In the recorded interview that followed, Seal acknowledged some, if not all, of his business with Rich Mountain Aviation. He told Duncan and Welch that he had warned the company’s owner that he stood “a good chance of going to jail” for the illegal modifications Rich Mountain Aviation had performed on his planes and that the owner had “better get himself a lawyer and be ready to look at pleading guilty.”

But five days before the grand jury was set to convene, Fitzhugh suddenly canceled Seal’s appearance, due to what he termed Seal’s “lack of credibility.” Duncan and Welch were incredulous. By now they knew that Seal had been invited to the Washington symposium largely because of the respect he’d won from U.S. attorneys for his testimony at high-profile trials. Duncan and Welch could not understand — and Fitzhugh never explained — why, at the last minute, he’d suddenly deemed Seal’s “credibility” insufficient in Arkansas.

Seal may not have intended to show up, anyway. The pressures on him had intensified since he’d agreed to testify against Jorge Ochoa, a cartel leader who was soon to be extradited to the U.S. To prevent that from happening, the cartel had placed a half-million-dollar contract on Seal’s head.

And it worked. On Feb. 19, 1986, a group of Colombian gunmen murdered Seal in the parking lot of a halfway house in Baton Rouge, where a federal judge had ordered Seal to spend nights while on court-imposed probation.

Barely four weeks later, Reagan appeared on national television to explain his opposition to Nicaragua’s Sandinista government. As part of that explanation, the president held up one of Seal’s photographs from inside the C-123. The image was grainy but Reagan said that it showed officials of Nicaragua’s Communist government loading cocaine onto a plane that was headed to the United States.

Reagan never mentioned Seal, and the photo’s authenticity was soon challenged. Nevertheless, that televised moment captured the whirlwind into which Seal flew after his move to Arkansas: the intersection of drugs, Central American politics, the DEA, the CIA and the U.S. president.

| KILLED IN BATON ROUGE: Colombian gunmen murdered Seal outside a halfway house on Feb. 19, 1986. |

We might never have known about any of that except for what happened on Oct. 5, 1986, less than eight months after Seal’s murder. The C-123 cargo plane he’d kept at the airport at Mena was once again flying over Central America when a Nicaraguan soldier shot it down. Papers found with the downed aircraft linked it to members of Reagan’s White House staff and with that, the political upheaval known as the Iran-Contra scandal burst into world news. Questions about the plane led to questions about Seal, and, inevitably, some of the fallout reached Hutchinson. The former U.S. attorney had lost his initial race for Congress, and by 1996, when he was running again, many Arkansans were trying to sort out his connection to Seal.

When someone at a campaign appearance asked the candidate if there’d been a cover-up at Mena, Hutchinson replied: “All I can tell you is I started the investigation. I pursued the investigation, and I was called to run for office. And after that I was out of the loop.” Hutchinson won his 1996 congressional race and two subsequent elections. He resigned from Congress in 2001 to accept an appointment by President George W. Bush as head of the DEA.

After a subsequent appointment at the Department of Homeland Security, Hutchinson returned to Arkansas, where he became the state’s governor in 2015.

Soon after taking office, Hutchinson installed veteran DEA agent Bill Bryant as head of the State Police. I came along a few months later, asking to see the agency’s file on Seal. When I learned how much less was available than reportedly had been in the past, I wrote to Hutchinson, hoping to ask about the difference, but he did not respond.

Bill Clinton, who was governor throughout Seal’s time at Mena, has also had little to say about the smuggler’s presence. While governor, Clinton was drawn uncomfortably close to questions relating to cocaine after police arrested his half-brother, Roger Clinton, on charges of distributing cocaine, and Roger Clinton reported that he’d gotten the drug from his boss, Dan Lasater, a Little Rock bond trader and financial supporter of Clinton.

Seal was dead by late 1986, when Lasater was indicted, but the FBI’s investigation of Lasater produced at least one intriguing connection between the two. Billy Earle Jr. had been in the co-pilot’s seat on that night in December 1983 when Seal flew into Mena to have an extra fuel tank installed. The following year, when Earle was arrested in Louisiana, Welch went there to interview him.

Earle told Welch that immediately after “the new plumbing” was installed, Seal planned to fly “to a place in southern Colombia, bordering Peru, and pick up 200 kilos of cocaine.” He said the trip was for an “operation to be staged out of Carver Ranch in Belize.” But, Earle said, that plan had fallen through.

In the fall of 1986, when FBI agents were investigating Dan Lasater, they questioned his personal pilot. That man reported that he had flown Lasater and his business partner, Patsy Thomasson, “to Belize to look at a horse farm that was for sale by a Roy Carver.” He said that flight had taken place on Feb. 8, 1984, within weeks of the aborted trip Seal had reportedly planned to the same location. Lasater and Roger Clinton both pleaded guilty to drug charges and served time in prison. After Bill Clinton’s election as president, he placed Thomasson in charge of the White House Office of Administration.

Though accusations abound, no link has ever been established between Clinton and Seal. Still, on the few occasions when the smuggler’s name has come up, Clinton has sounded as “out of the loop” as Hutchinson.

At one point, while Clinton was governor, the local prosecuting attorney for Mena had attempted to act where U.S. attorneys Hutchinson and Fitzhugh had not. Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Charles E. Black wanted to impanel a state grand jury to consider evidence that people at Rich Mountain Aviation had abetted Seal’s drug-trafficking operation. Realizing that such a case would cost more than his district could afford, Black had asked the governor’s office for a grant of $25,000. But Black said he never received a response.

Bill Alexander, one of Arkansas’s long-term Democratic congressmen, supported Black’s idea. Alexander told me that he wrote to Clinton personally, repeating Black’s request and explaining that questions about Seal needed to be “resolved and laid to rest.” But he, too, said that he did not recall receiving a response.

Yet, later on, when a reporter asked Clinton what he had known about Seal, the governor had a somewhat different recollection. He said that, although he had authorized payment of $25,000 to fund the grand jury Black had requested, “Nothing ever came of that.”

On the subject of Seal, the usually astute governor had come across as unusually uninformed. A citizens’ group called the Arkansas Committee suspected that state and federal authorities had agreed to protect Seal in Arkansas. Disturbed by Clinton’s apparent disinterest, members of the group at one point unfurled a 10-foot-long banner at the state Capitol that asked: WHY IS CLINTON PROTECTING BUSH? In 1992, when Clinton and George H.W. Bush opposed each other for president, neither candidate mentioned Seal.

After Clinton’s election as president, when White House correspondent Sarah McClendon asked him what he knew about Mena, he remained adamant but vague as he mischaracterized Black’s investigation. “It was primarily a matter for federal jurisdiction,” he said. “The state really had next to nothing to do with it.

“The local prosecutor did conduct an investigation based on what was in the jurisdiction of state law. The rest of it was under the jurisdiction of the United States attorneys who were appointed successively by previous administrations. We had nothing — zero — to do with it, and everybody who’s ever looked into it knows that.”

Almost a decade after Seal’s death, U.S. Rep. James A. Leach (R-Iowa) took an interest in what one of the people he questioned, CIA Director John Deutch, later described as “allegations of money laundering and other activities” in Mena. As chairman of the House Banking Committee, Leach was well positioned to investigate such claims. He told reporters: “We have more than sufficient documentation that improprieties occurred at Mena. This isn’t a made-up issue. There are grounds to pursue it very seriously.”

In a letter to the DEA, Leach asked the agency to provide all documents relating to “possible ties between activities at Mena Airport and the use of a private airstrip at a similarly remote location near Taos, New Mexico, at a ski resort called Angel Fire” — a resort owned by Lasater. Leach wrote: “Published reports indicate that DEA conducted at least two separate investigations of alleged money laundering and drug trafficking in or around Angel Fire, the first in approximately 1984, and the second in 1988-1989.” He said the second investigation was triggered by allegations from former Angel Fire employees “that the resort was the focal point for ‘a large controlled substance smuggling operation and large-scale money laundering activity."

| TOM CRUISE AS BARRY SEAL: In “American Made,” opening Friday (courtesy Universal Pictures). |

Leach added: “The alleged activity at Angel Fire was roughly contemporaneous with the money laundering and narcotics trafficking alleged to have taken place in or around Mena Airport during the period 1982-1986.”

Leach sent congressional investigators to Arkansas. And he asked the U.S. Customs Service what it knew about “the disposition of potentially ill-gotten gains by Seal or his associates,” especially with regard to “a piece of property in Belize known variously as the Cotter, Cutter or Carver Ranch,” because, “Barry Seal allegedly used this property in his narcotics trafficking operations and attempted to buy it in 1983.”

Little more was heard of Leach’s investigation for the next three years. Finally, in 1999, a reporter for The Wall Street Journal inquired about its status. Leach’s spokesman responded that investigators were “putting the finishing touches” on their report.

But that was the last the public heard. The House Banking Committee’s investigation into what Leach called the “improprieties” relating to Mena has never been released.

And my book, “The Mena File?” It was not published, either. I’d completed the manuscript, with hundreds of supporting notes, by this time last year. Lorenzen, who had prepared the index, was pleased. The book was listed in the University of Arkansas Press catalog and for presale on sites such as Amazon.com.

It was time for an attorney to read the manuscript to make sure it contained nothing libelous. This vetting process is standard for books of contemporary nonfiction, especially those involving crimes. Having been through the process with publishers of my other books, I understood the need and was ready. I was also unconcerned, in part because I’d been careful, but also because the most serious allegations — those concerning Rich Mountain Aviation — had already been vetted years ago for a section about Seal in my book, “The Boys on the Tracks.”

But I was in for a shock. Lorenzen told me that his boss, David Stricklin, the ASI’s director, had suddenly expressed some “concerns” about the book. Lorenzen further reported that, while these concerns were legal in nature, Stricklin had said the ASI could not afford to have the manuscript vetted.

Neither the decision nor Lorenzen’s explanation that “we’re just a shoestring press” made sense. From the start, the book was intended to be a solid work of Arkansas history buoyed by a major Hollywood film. What’s more, Random House had already contracted to buy its audio rights and paid an advance.

From a business point of view, the ASI’s position defied logic. I asked Lorenzen if the newly arisen concerns might be political rather than financial, but was told nothing more. Lorenzen proposed rescinding our contract. Seeing no reasonable way forward, I agreed. As I’d written the book without an advance, the deal’s undoing was simple.

•••

By now I’ve had a year to reflect on my experiences in writing about Seal, as well as those of Duncan, Welch, Black, Alexander, members of the Arkansas Committee, and others who’ve tried to shed light on his time in Arkansas. None of us much succeeded.

So I’m glad that at least Hollywood has found Seal’s “true lies” worth exploring. Too many secrets have been kept for too long; too much important history has been hidden, lost or destroyed. Let’s hope that Cruise’s high-powered version of Seal prompts an equally high-powered demand for disclosure of all government records on him, especially after his move to Mena.

Mara Leveritt is author of “The Boys on the Tracks,” “Devil’s Knot” and “Dark Spell.”

Reproduced with Permission

Copyright © 2017 Arkansas Writers’ Project, Inc.

All Rights Reserved