SALINE COUNTY SHERIFFS

Sham Investigations By Six Sheriffs

James Steed

1979 - 1990

Larry Davis

1991 - 1992

Judy Pridgen

1992 - 2001

Phil Mask

2001 - 2009

Bruce Pennington

2009 - 2013

Cleve Barfield

2013 - 2014

Rodney Wright

2016 - Present

Steed Set The Standard For Sham Investigations

Our web researcher and historian, Ron Dane, has produced a series of video documentaries on his page of our website. Ron chronicles events with documentation that is indisputable and he tells his stories with amazing skill and organization. In Murder On The Tracks Part 3 – The Sheriffs, Ron looks at the deliberate sham investigations from Sheriff James Steed to the current Sheriff Rodney Wright. Although the jury is still out on Wright, Linda and Jean always find optimism in each new purportedly legitimate inquiry, but time will tell. An excellent introduction to Ron’s work is The Sheriffs (to the right) in which he discloses the true intention of each Saline County Sheriff regarding the murders.

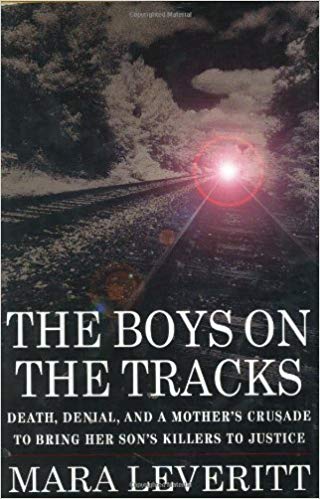

Murder On The Tracks

Part 3 – The Sheriffs

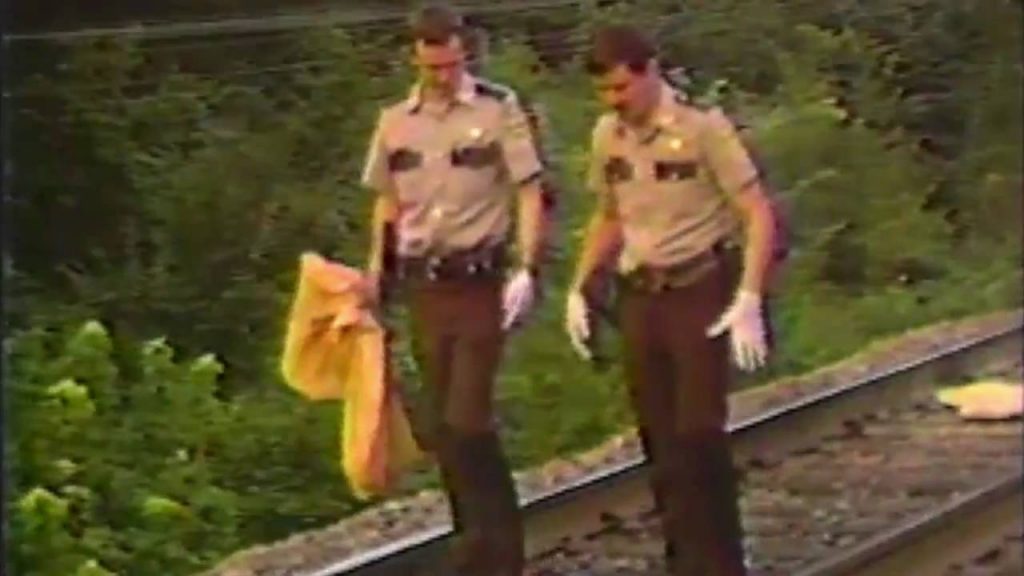

The Initial Crime Scene Investigation by Sheriff James Steed

Saline County Sheriff Steed’s investigation of the crime scene was grossly incompetent or deliberately deceptive and certainly set the standard for future sheriffs. An excerpt of the initial so-called investigation of the crime scene from Mara Leveritt’s book, The Boy’s on the Tracks, poignantly details the events that will infuriate the reader like nobody does better than Mara. These events launched Linda’s transformation from a content “football and drill team mom” into a warrior. In the words of our researcher, Ron Dane, “they poked the wrong mama bear.”

Linda's Open Letter To Sheriff Steed

2/9/88

An Open Letter to Sheriff Steed:

Sheriff Steed, you have stated that you are satisfied with the investigation your department has conducted in the death of my son, Kevin Ives, and his friend, Don Henry. You have also insinuated that our dissatisfaction with the investigation stems from the personal tragedy that we have suffered. I would like to point out to you, as well as the public, some of the reasons that we are dissatisfied.

(1) It is a fact that the area was never roped off as a “protected crime scene.”

(2) The area could not possibly have been searched thoroughly for evidence of a crime. After the investigation of the scene was completed, family and friends went to the area and found Kevin’s foot, the gun stock and other parts of the gun Don had, and other personal belongings, of the boys’. I consider this clear evidence of how well the area was searched.

(3) We were informed about reports that two people had heard gunshots shortly before the “accident.” Saline County Sheriff’s Office (SCSO) assured us that tests would be done on the gun Don carried, but tests were never done.

(4) We were assured from the very beginning that SCSO would request assistance from the State Police. Colonel Goodwin informed me that a request was never received in his office. It is a fact that there is no State Police report of any kind filed on the “accident”.

(5) Three train crew members reported a green tarp partially covering the boys as they lay on the tracks. One of the crew saw where it landed and shined a light on it and informed SCSO where it was. SCSO assured us they would personally interview the train crew rather than rely on the railroad investigators report. That never happened either. They now tell us that this green tarp was an “optical illusion”.

(6) There was information given to SCSO that could have developed into a possible lead, but the informant was never contacted

(7) Don’s Stepmother found a partial bag of marijuana in Don’s jeans pocket on 2/5/88 — nearly six months after Don’s personal effects were returned to her. A SCSO deputy said they turned the boys’ clothes inside out, but somehow, they missed the bag of marijuana (evidence and contraband). What else was missed besides a foot and marijuana????

(8) The back of the train was used as a reference point for gathering evidence, so when the train pulled away, the reference point was lost forever.

These are just a few of the things regarding SCSO’s investigation that we are unhappy over — some things we know about. I shudder to think what we do not know about.

AND LAST OF ALL SHERIFF STEED, YOU HAVE NO FIRST HAND KNOWLEDGE OF THIS INVESTIGATION THAT YOU ARE SO PROUD OF. YOU DID NOT EVEN BOTHER TO GO DOWN TO THE SCENE NOR HAVE YOU EVER CONTACTED US PERSONALLY REGARDING THE DEATH OF OUR SONS.

Linda Ives

Linda's Commentary on Mara Leveritt's Book

In the book excerpt below you can see that Mara Leveritt’s investigation of the crime scene is far superior to that of Sheriff Steed’s.

” A look at the 1987 deaths of two Saline County Teens.”

By Mara Leveritt

By all accounts, the engineer did a masterful job of bringing his train to a stop. It had taken a screaming, screeching half mile. By the time the engine shuddered to a standstill, Conductor Jerry Tomlin was on the radio notifying an approaching train on a parallel track to stop because some boys had been run over. He also called the dispatcher. “Have you got injuries?” the dispatcher asked. “No,” Tomlin said. “We’ve got death. I’m sure we’ve got death. They passed under us. It has to be death.”

The three men in the union pacific locomotive, all railroad veterans, were holding themselves together, trying to cope with a sudden nightmare at the end of a routine run. It was a little after 4 A.M. on Sunday morning, August 23, 1987. They were coming north from Texarkana, pulling a rattling mile of freight and empty cars. The trip toward Little Rock was uneventful, the weather mild, the temperature about 80 degrees. Later, each would remember the night as having been particularly dark.

For miles they’d felt the landscape rise beneath them as the engines hauled the train up from south Arkansas’s tree-farm flatness into the rolling countryside surrounding the capital. At the slumbering town of Alexander, about 25 miles south of Little Rock, the train topped a moderate hill known locally as Bryant Hill, then descended quickly into bottomland, a low-lying stretch of topography prone to flooding in heavy rains. But high water was no problem tonight. All that Engineer Stephen Shroyer had to worry about on his descent was keeping his train in check and making sure it stayed within the federal speed limit of 55 miles per hour. He was still braking the train hard as it approached the Shobe Road crossing.

Shroyer sounded his horn as required. There was not a car, not a person, in sight.

From his place in the lead engine’s right-hand seat, Shroyer concentrated on controlling his speed. Beside him on the left, Danny DeLamar, the brakeman, helped. Behind DeLamar, Conductor Jerry Tomlin completed paperwork for the trip. By now their train had traveled about a half mile past the crossing at Shobe Road. They were approaching a small trestle over a trickle called Crooked Creek. It was not even a trickle on this dry August night.

“Our headlight was on the ‘bright’ position,” DeLamar later recalled, “and I noticed down the rail in front of me, some 10 or 15 cars away, there was a dark spot on the rail. I looked hard at it, and towards the last, I stood up to see what it was.” Shroyer also stood up. So did Conductor Tomlin.

The men knew from experience that when a bush or other debris is picked up by the light, the spot on the rail will often appear dark. Any obstruction is a concern. The men peered intently ahead. In the same, heart-stopping instant, they realized what they were seeing.

“When we were approximately 100 feet away from this dark spot, Engineer Shroyer yelled out, ‘Oh, my God!’ He hit the whistle and the emergency brakes at the same time,” DeLamar recalled. “We could tell there were two young men lying between the rails just north of the bridge, and we also saw there was a gun beyond the boy who was lying to the north. There was something covering these boys from their waist to just below their knees, and I’m not sure what this object was. They were both in between the rails, heads up against the west rail, and their feet were over the east rail. Both were right beside each other and their arms and hands were to their sides, heads facing straight up. I never noticed any movement at all.”

At 55 miles per hour the crew had fewer than five seconds to respond. Reflexively Shroyer shoved the brake forward to its emergency position. The move is a desperate one, producing such sudden jerking and slacking that the engineer risks losing control.

Steel wheels scream on steel tracks. If the braking continues long enough, the wheels will be ground flat on the bottom. For at least four seconds the train resisted Shroyer’s efforts, banging and screeching, wailing its violent approach to the motionless figures ahead. The brakes exhaled a gasping whoosh of air. The cars vibrated.

The tracks vibrated. The horn never went silent. And still, to the crewmen’s mounting horror, the boys did not jerk, did not open an eye, did not move a muscle.

Tomlin dropped his paperwork and lurched forward between Shroyer and DeLamar to get a better look. “When we recognized that it was two people,” he recalled, “I hollered, ‘Big hole!’ which means for the engineer to set the brake in emergency. I saw two boys lying side by side, like soldiers at attention. There was a dark-headed boy to the south — that was the one we were going to hit first — and the second boy had lighter hair. They were covered up to around the waistline with a pale green tarp, something like a boat cover. They looked like they had lain down there and pulled this cover up on them like a blanket, but part of it was off. I noticed they never moved. Here we were, bearing down on them, and there was no movement of their heads. They made no attempt to rise.

“And there was that rifle. It was lying flat on the ground, the barrel part near the boy’s head, the stock under the cover.”

That was all there was to see. Then the sight was gone, vanished beneath the train. “We could hear them hit,” Tomlin continued. “You can hear it even when you hit a dog. It’s mostly a thud and then you hear some rocks flying because, if what you hit is still under the train, you’re scooting it along.”

With his hands on the controls, Shroyer felt the impact like a body blow, one from which he’d never quite recover. “I was standing and continued to blow the horn until we had impact,” Shroyer recalled. “There were the two boys and then the weapon, all very one-two-three. And there was a piece of green material, very light, very faded. It looked well worn, laying out on the boys, and it looked like it had blown back, partly exposing them. The first boy had on a shirt, blue in color. The second boy did not have a shirt on. From my observation, they were both in a totally relaxed position. There was never any movement. There was no flinching, even with the whistle, and the train bearing down on them. Their feet were on my side of the engine, extending across the rail, and I remember noticing their feet were in a totally relaxed position. That’s the thing that caught my thoughts, was how completely relaxed they were. And the thing that caused me so much problem afterward was the fact that they didn’t flinch, didn’t jerk, didn’t move at all — either one of them — with all of it happening, all that noise, all of it coming down on them.”

Shroyer’s attention was riveted on the boys. “I never took my eyes off them,” he said. “What had caught my attention at first was a big brilliant flash. Apparently that was my headlight striking the barrel of the gun. The next thing I was totally aware of was the chest and the head of that second boy, the one without the shirt. And from then on, I never took my thoughts off of him. What I focused on were his chest and his head — and how relaxed he looked. To me he looked as relaxed as a boy sunbathing on a beach.”

The image of two boys appearing so calm as death was about to roll over them was almost more than the men could absorb. Yet the one thing more certain than the boys’ immobility was the impossibility of stopping the train. Shroyer recognized the onrushing inevitability in a nauseating wave of despair.

“Your immediate thought is, My God, please get out of the way! And you can’t stop,” he said. “You can’t stop a train that fast, and it’s a hopeless feeling.”

Shroyer was enough of a veteran to realize that he, like his train, was verging out of control. “When we hit them, they rolled with us,” he said. “They stayed with the engines for a while. My immediate reaction was that I was traumatized. My thoughts, and everything else, you know — my God, you know — I was holding on. I was thinking, Please, this is not really happening.

“I allowed my engines to lock up and felt my train operation just going to hell. When that happened, I immediately realized I had to get back to the business at hand. I had to get my train under control again. And I did. But when it happened, there was nothing we could do. I just know that, without a doubt, if willpower could have had anything to do with it, that train would have stopped. We would not have run over those boys.”

When a train hits an object on the tracks, one of two things usually happens. Either the scoop on the front of the engine, commonly called the cowcatcher, will toss the object violently aside, or the object will be sucked up under the engines, tumbled a while, and be tossed out. By the time it’s ejected, the struck object has picked up the speed of the train.

As their train slowed to a stop, the crew could imagine the destruction their locomotives had wrought on the human flesh beneath them. The boys’ legs, which had been draped across the rail, would have been severed immediately, sliced off by the first right wheel, somewhere between the knees and the ankles. Because the heads and torsos were between the rails, the train had most likely cleared them, resulting in the bodies being rolled, which fit with what the men had heard–and felt. After that, pieces of bodies would have been spit out from beneath the engines, probably in all directions.

Once the train had stopped, the crewmen wasted no time. Shroyer would stay with the radio to keep in touch with railroad officials. Tomlin and DeLamar would walk back to confront the mayhem. “If you start to get sick, go right ahead,” Tomlin told DeLamar as the two picked up their flashlights and climbed out of the engine.

About thirty-five cars back they located the first pieces of body, a trio of dismembered toes. Over the course of the next hour or so, they found evidence of the carnage scattered along a quarter mile of track. The single biggest body part they found was the chest and head of the second boy, the one without a shirt. The body of the first boy was considerably more chopped up.

In those eerie first few minutes before the police arrived, while the crewmen struggled to control their emotions, a disturbing half thought lurked at the edge of their minds. It was a barely formed thought, one almost too troublesome to admit. But here it was: the boys had not moved or flinched. And now, though neither man spoke of it, they noticed something else. The scene was a bloody mess, but there was something wrong with the blood.

Like many Arkansans, Tomlin had hunted since childhood. He’d seen many a fresh-killed deer, field-dressed dozens of them. He knew how animals bleed, especially when they’ve just been killed; he knew how fresh blood flows.

But this blood wasn’t like that. As a matter of fact, “There was very little blood,” Tomlin later recalled. “Even with all those wounds, with everything cut up. We had reached the bodies within 10 minutes after impact. You would think that if the heart had been pumping when we ran over the boys, then the blood would have naturally flowed out. But it wasn’t flowing. There was hardly any blood at all. And the color of it bothered me, too. It was night, and we couldn’t tell for sure, but the blood we saw was not red — not as red as you would think blood would be on a fresh kill like that. It was dark, more of a purplish color.”

For Tomlin, the blood suggested something odd. “out there that night,” he said, “I kind of smelled a rat.”

The site where the bodies lay scattered that exceptionally dark August morning was in a rural, unincorporated area under the jurisdiction of the Saline County sheriff’s office. Deputies responded to the dispatcher’s call. By 4:40 A.M., 13 minutes after the crew reported the collision, Deputy Chuck Tallent and Lt. Ray Richmond, head of the department’s criminal investigation division, arrived at the span of tracks just past the trestle alongside some woods. Tallent set to work diagramming the scene, mapping out the locations of various body parts and other pieces of evidence as they were discovered. Soon an Arkansas State Police trooper arrived, then officials from the railroad, then an ambulance.

The investigators’ arrival did little to calm the crew. The train men had hoped to make their reports, then leave the matter to the authorities. Instead, as they spoke to the police they found their misgivings heightened.

The crew did not realize it at first — no one did — but hope for an accurate reconstruction of the scene ended within minutes of the deputies’ arrival. In diagramming the site, Tallent made an immediate and crucial mistake. He chose as his reference point the corner of one of the train cars and mapped everything in relation to that.

Hours later, when the train was allowed to move forward after most of the evidence had been bagged and removed, that reference point was lost forever. The diagram of where each piece of evidence was found became virtually worthless. It was a costly mistake, one that, when it came to light several months later, undercut public confidence in the deputies’ investigation and exposed the sheriff’s office to ridicule. So did the decision, made soon after the deaths, to let a second train that had been waiting pass, further disturbing the scene.

To the even greater astonishment of the crew, Tallent and Richmond appeared to be treating the deaths as an accident despite the railroad men’s urgent accounts of having seen the boys lying side by side, unmoving, as the train approached. The deaths did not look like an accident to the crew. As Tomlin blandly observed, “One boy not moving — maybe. But two? I have some trouble with that.”

Still, the crew had to acknowledge that accidents involving trains did happen, and so did suicides. They all knew there had been at least two suicides by train in Saline County within the past eight years. Such things happened. The crew let the police do their job.

But the treatment of the deaths as suicides, or an accident, was unsettling to others as well. Hours earlier, Trooper Wayne Lainhart of the Arkansas State Police had investigated a report of two shots having been fired in the area. His look-around had turned up nothing.

Now, though the deputies had jurisdiction, he also responded to the scene and heard the train crew’s statements.

Lainhart’s assessment, as he later recalled, was that aspects of the situation didn’t seem quite “kosher.” Part of what bothered him was the deputies’ apparent disinterest in the possibility of murder. According to Lainhart’s training, any unnatural death should be investigated first as a possible homicide so that evidence can be preserved and the most serious possibilities eliminated before less serious ones are considered. The practice is standard police procedure. But not all police, especially in small, rural sheriffs’ offices, receive the training offered state troopers. Lainhart let the deputies handle their investigation. Still, it disturbed him to see such a basic rule so quickly abandoned, and in such a strange case.

Lainhart mentioned his misgivings to the deputies, noting that he doubted the deaths were an accident, but he did not press the issue. Nor did the two emergency medical technicians who arrived on the scene a couple of minutes later and who immediately found causes of their own for alarm. One of those EMTs was Billy Heath, who later talked to a state police detective. “Mr. Heath stated the bodies looked more like mannequins, that there was very little blood at the scene, and that the blood at the impact site was very dark,” the investigator noted. “Mr. Heath stated the blood was just too dark for him to consider normal. Mr. Heath stated he did not see any bright blood and that, in his opinion, there should have been some fresh blood at the scene.”

The other attendant, Shirley Raper, reached the same conclusion. “We grabbed our paramedics’ equipment and took off down the tracks,” she later told the state police. “Billy reached the first body, and he told me to stop and not to come any closer. I just observed the one body and it occurred to me right off that it was strange, because of the lack of blood and the color of the body parts and the color of the blood. The body parts had a pale color to them, like someone who had been dead for some time.”

In an unusual move, and one they knew could be controversial, the two paramedics attached what they titled a “note of interest” to their official report on the incident, a report prepared within hours after leaving the scene. The note read, “Blood from the bodies and on the body parts we observed was a dark color in nature. Due to our training, this would indicate a lack of oxygen present in the blood and could pose a question as to how long the victims had been dead.”

While the train crew, the state police trooper, and the two paramedics all expressed misgivings, Tallent and Richmond proceeded to treat the deaths as a probable accident or a double suicide. Only one officer vigorously objected. Deputy Cathy Carty surveyed the scene, listened to the train crew’s account, and heard the paramedics’ misgivings. She then confronted her superior officers, protesting their disregard of the possibility that the boys had been murdered. She was infuriated when Richmond ordered her and other deputies to treat the case “like a traffic fatality.” Later Carty recalled, “I told the coroner, ‘We either have two of the damnedest suicides I’ve ever seen here or we have a double homicide.'” But Carty’s objections were to no avail. The scene was investigated in the manner of a traffic accident, and the bodies were sent to a funeral home, since traffic accidents did not require an autopsy in Arkansas. Within hours, however, Tallent changed his mind and redirected the bodies to the state crime lab where they would undergo autopsies.

That came as good news to the train crew. But their long night was not over. By the time the sun was rising and the investigation, such as it was, was winding down, they were to be unsettled by yet another peculiar aspect of this sickening morning. A disagreement arose over the piece of faded green tarp that Shroyer, Tomlin, and DeLamar had seen on top of the boys. For reasons that none of the crew could fathom, the police appeared reluctant, if not actively resistant, to accept their unanimous reports that such a covering had existed. The crew could not imagine why their statements on such a neutral piece of information would be met with disbelief.

Tomlin was especially unnerved by the reaction. He had walked the tracks with his flashlight, looking for that tarp, and had found it.

Having apparently blown off the boys upon impact, it had landed at the base of the trestle. Shining his flashlight on the tarp, he had pointed it out to Deputy Tallent.

“He denied that later,” Tomlin recalled. “He said I didn’t tell him about finding the tarp, but I did. And I told him where part of it was, at the bridge bulkhead. I remember it as well as I remember him. I’m pretty observant. I catch most stuff. I remember seeing that tarp as well as I remember how Tallent was dressed that morning. He had on a navy blue or black ball cap that said SALINE COUNTY DEPUTY. He was wearing cowboy boots and blue jeans. He had on a belt buckle that also said SALINE COUNTY SHERIFF’S OFFICE. He had a package of cigarettes rolled up in his shirtsleeves, like a sailor going on leave. And he had his pistol, an automatic, stuck in the back of his pants, like Magnum, P.I.”

Inexplicably, Tomlin felt that much of what the train crew had told the deputies was being dismissed. The reaction perplexed and angered him. “We all saw the tarp,” he said. “They were definitely covered up from their waist down to their feet with it. But he told us it must have been an optical illusion. Just like the gun. When he first arrived and we told him there’d been a gun, he acted like he didn’t know what we were talking about. Then when we were walking along the tracks the deputies asked me where this ‘alleged gun’ was. We had to take them and show them where it was. We’d already found that, too.”

The cool and minimalistic police approach contrasted sharply with the out-of-control and gruesome quality of the scene, and that sense of dissonance that had left so many unsettled on Sunday returned with a vengeance the following day. On Monday, after an account of the deaths made the television news and the papers, relatives and curiosity seekers flocked to the tracks. There, one of them discovered a severed foot lying in the gravel. To the train crew, still stung by the attack on their professionalism, such carelessness by the deputies seemed unconscionably unprofessional.

“I’m just an old country boy,” Jerry Tomlin later complained. “I was born at night, but I wasn’t born last night. And I can tell you, I didn’t think too much of the investigation. The deputies’ attitude was more like ‘Let’s get this cleaned up and get back to the coffee shop.’ I don’t know. People don’t realize what a mess it was. Maybe they were in shock. Maybe they had weak stomachs. Maybe they just didn’t want to face it. Whatever it was, I sensed all along that they were not out there looking for clues.”

For Shroyer the night would leave a permanent scar. “I was rattled,” the engineer later told an investigator. “There’s no question, I was rattled. I was sick of everything that there was about the whole situation. But I maintained my professional stance. When my superintendent arrived, I halfheartedly apologized for being shaken. I told him I didn’t understand why it was affecting me so deeply, except for the fact that it was kids. And the situation was just not right. And it disturbs me to this day. It really does. The thought of it, of what happened to those kids, why they were there, what was going on… I’ve lived with it. I’ve looked at it. And it does not add up.”

The deputies admitted to being somewhat bewildered by the events. Two days after the deaths, Chief Deputy Rick Elmendorf told the local newspaper, “We are trying to come up with any feasible reason for something like this to happen.” And he added, “We haven’t ruled out anything except foul play.”

Copyright ©1996, 1997, 1998, 1999 Arkansas Writers’ Project, Inc.