Speaking Out

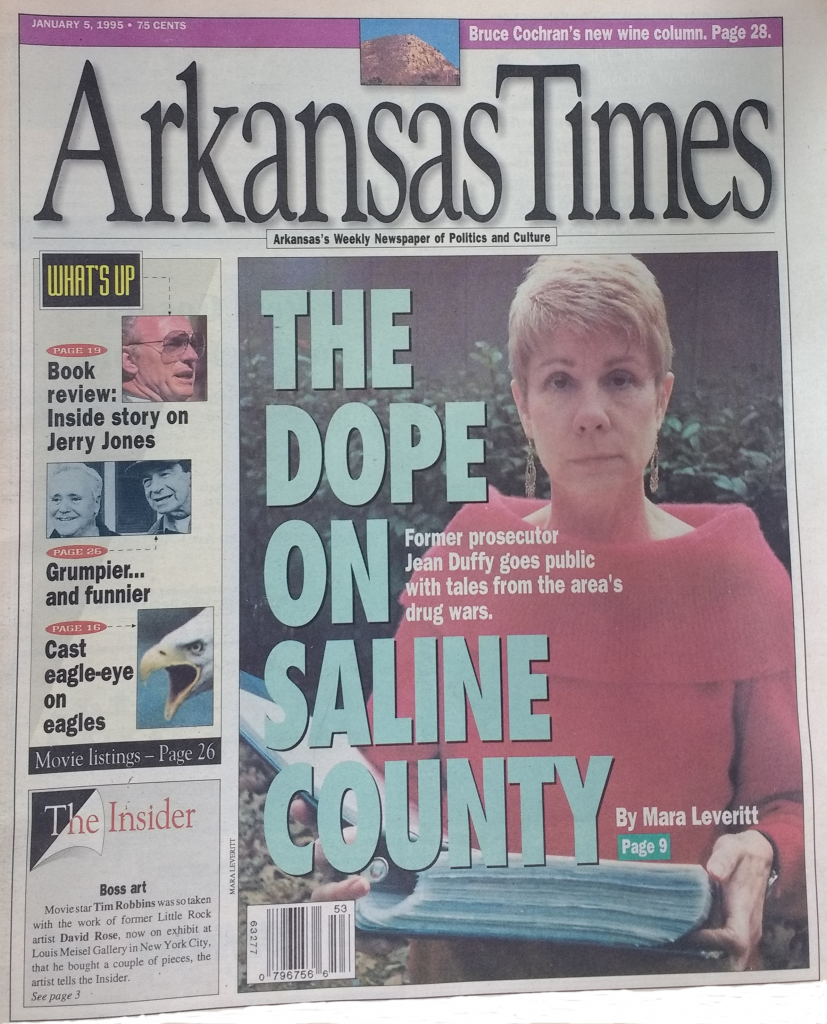

Former Saline County Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Jean Duffey is talking about the unsavory doings surrounding the county’s drug task force.

The Dope on Saline County

A former drug task force head reveals details of her brush with Saline County justice in this Arkansas Times article.

January 5, 1996

Arkansas Times

Cover Story

By Mara Leveritt

In the past few weeks, Dan Harmon, the pit-bull prosecuting attorney for the 7th Judicial District, has found himself backed into something of a corner. As prosecutor, Harmon is responsible for operating the drug task force in Saline, Grant, and Hot Spring counties. The task force’s current director, Roger Walls, reports to Harmon. The snarl for Harmon and Walls these days is that a few weeks ago, drug packets that should have been in Walls’ evidence locker, which is kept at Harmon’s office, were found by the Garland County sheriff’s office in the possession of Holly DuVall, Dan Harmon’s most recent ex-wife.

Jean Duffey was not surprised by the news. Duffey was a deputy prosecuting attorney in the 7th Judicial District in 1990, when federal money became available to establish the state-wide system of drug task forces. Duffey had a record for aggressively prosecuting DWls, and because of that, she was offered the job of establishing the district’s new drug task force.

It turned into a nightmare. After just eight months, Duffey was fired amid a barrage of public accusations against her by Harmon.

At the time, she did not respond. Now, after five years of silence, Duffey is ready to talk. Surrounded by boxes of notebooks, task force records, and Arkansas State Police investigative reports and newspaper clippings, she leans forward in her chair and immediately raises the name of Gary Arnold, her former boss, the prosecuting attorney in the district at the time, and Dan Harmon’s predecessor in office.

“When I was hired,” Duffey says, “Gary Arnold looked at me sternly and said, ‘You are not to use this drug task force to investigate any public officials.'” She sits back and exhales. “I’ve been dying to say that for years.” Arnold won’t talk about Jean Duffey.

In 1990, Jean Duffey was a 43-year-old deputy prosecuting attorney with a good record for convicting drunk drivers. When money came down for the new drug task force, the men who were appointed to serve on its board—the sheriffs and police chiefs from Saline, Grant, and Hot Spring counties—asked Duffey to set up the new law enforcement agency and to serve as its first director.

Twice she declined. On the third request, Duffey accepted, but, she told the board, she’d only serve for a year.

That was in March. By November, the task force had seen its operations shutdown three times, often for weeks at a time. its books had been the subject of an Arkansas State Police investigation. Duffey’s name had been dragged through the press, where Harmon linked her to some $4,000 in missing task force funds, phony drivers’ licenses, and frivolous prosecutions. In November, the board fired Duffey. She found public support from three of the task force’s six undercover agents, who, according to Duffey and one of those agents, Scott Lewellen, resigned their jobs in protest.

At a news conference announcing his resignation, Lewellen told reporters that Duffey’s firing was an attempt to stifle the task force because of what it had been uncovering: a mounting pile of information that appeared to link certain public and police officials in the district with drug-dealing.

“We discovered those connections through drug cases we developed,” Lewellen said at the news conference. Two additional investigators later resigned.

But the protest was no match for Harmon’s ferocity.

Duffey remained quiet, and the prosecutor’s accusations dominated the news. Even years later, an article in the Arkansas Times by John Brummett typified what had become the media consensus. In a profile of Harmon, Brummett referred to the former task force director as “the discredited Jean Duffey.”

Now Duffey thinks it might be Harmon who’s looking a bit discredited. Back in Arkansas to respond, ironically, to a lawsuit she links to Harmon as part of an alleged personal harassment campaign against her, Duffey is ready to fight. As she begins throwing her punches, the dust she raises and its potential for damage may not be limited to Harmon.

Duffey says that when her boss, then prosecuting attorney Gary Arnold, spelled out the limits on the drug task force’s scope—that it was not to investigate any public officials— the demand did not sound an alarm at first. That was because Duffey knew, as did Arnold and almost everyone who worked for the 7th Judicial District, that federal officials were at the time conducting their own investigation into public corruption there.

“We’d heard the rumors about public corruption for years,” Duffey, a native of Malvern, says, “but nobody inside the district seemed to be able to get at it. That federal investigation was our last hope.”

By 1990, when Duffey’s task force was established, many residents believed an independent investigation of district political figures was long overdue. Benton has long been regarded by police in central Arkansas as a hub of illegal drug activity, and suspicion that some of that activity has been sanctioned by public officials has been rampant.

During the 1980s, Saline County, in particular, experienced a series of unsolved murders, including those in 1987 of two teenagers who were beaten and run over by a train and of a police informant, a bouncer known for being able to fight, who was found dead in his driveway, stabbed 113 times. Numerous investigations into those murders, while failing to solve them, turned up several informants’ statements that linked Harmon and other public officials to drug trafficking in the county.

In the late 1980s, Larry Davis campaigned for sheriff of Saline County on a promise to investigate those allegations. After he was elected, (and apparently saw that job was too big or too tricky for his own office to handle), he appealed to federal law enforcement officials. Chuck Banks, who was at the time the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas, agreed to launch an investigation into public corruption in Saline County. He assigned the case to an assistant U.S. attorney, Robert Govar.

That investigation was going full swing when Duffey was invited to set up the drug task force. She says that in February 1990, the month before she began organizing the task force, Arnold showed her a copy of a memo written by Govar to Banks, that was dated two weeks earlier.

The memo detailed elements of the federal investigation. It contained statements that appeared to implicate a judge and a longtime associate of Harmon’s.

But the most damaging statements in the memo concerned Harmon himself. One sentence read: “We have developed a pretty substantial amount of information concerning the drug use and dealing of Teresa Harmon [another former wife] and Dan Harmon.” The memo, which was leaked to the press several months later, detailed witnesses’ claims of having seen Dan Harmon using drugs, buying drugs, and watching while his wife, Teresa, sold drugs. [Authorities recently claim to have connected Teresa Harmon with an attempt to send methamphetamines by express delivery service.] In addition, there was mention of bribes and of cases being “fixed” in the memo.

In light of Govar’s investigation, Duffey says she took Arnold’s demand that the drug task force was not to investigate public officials as an attempt not to cross investigative lines and duplicate the federal effort. She agreed to focus the task force’s efforts on “street-level” drug-dealing in the district.

Duffey hired a fiscal officer, Kathy Evans, to manage the task force’s funds, and six investigators to work the three-county area. She says problems developed almost immediately.

“It didn’t take but a few weeks before my undercover officers began coming back with information on public officials,” she says. “They began developing their confidential informants, and in almost no time at all they started getting this information relating to Harmon [who by then had won the Democratic primary for district prosecuting attorney ] and other public officials. It all happened very quickly. It was amazing.”

According to Duffey, information surfaced on other district officials as well. “We ran across situations where certain case files didn’t reconcile with the arrest records,” Duffey says. “There were instances where weapons, vehicles, drugs, and money had been confiscated, but the records didn’t line up with the final court orders on the disposition of those items.

Most of the time in the cases we examined, there was no disposition whatsoever of the confiscated property. At that time, it was mostly weapons and vehicles, that appeared to be the problem. But there were cases of missing money, as well.”

Duffey says she channeled all the information relating to public officials to Govar at the U.S. attorney’s office. “I’d type it up on the computer. I didn’t even keep a copy. I’d write it. I wouldn’t save it. I printed it out, and I closed it. Then I’d send it on to Govar.

“We were busy enough with everything else we had to do. But as time went on it became impossible to focus on drug dealing in our district without including reports on public officials. We were beginning to realize we were not ever going to be able to go too much above street-level dealing without finding a public official.”

As a prosecutor, Duffey says she began to realize the situation posed several peculiar problems. One of them was the matter of how to bring drug dealers’ cases to court without involving the public officials with whom they appeared to be involved.

“I had said from the start I was only going to serve until the first of the year,” Duffey says. “I figured we would conduct the investigations and then I would hand them over to someone else to figure out how you prosecute these cases and put the witnesses on the stand without bringing in the public officials.”

Looking back, Duffey sees the situation as having been impossible from the start. The biggest obstacle, she says, was with the influence some officials had on the drug task force’s board.

Duffey says one of her biggest problems was with Gary Arnold, the prosecutor who hired her. Arnold appointed the task force board of directors that had hired her to be administrator, but he was the only member who did not vote to approve her.

Duffey says she did not understand his apparent change of attitude. “Something happened,” she says, “between December, when he asked me to be his chief deputy prosecutor and March when he didn’t want me on the task force. He abstained. He refused to vote. The others voted for me unanimously.”

According to Duffey, just as the task force got organized, and its undercover agents began working in the district, Arnold temporarily shut the operation down.

She says, “The first time we were shut down was for two weeks because Gary Arnold said he wanted to investigate our officers’ liability insurance. But that didn’t make sense. Our officers were sworn in as county deputies, as they were in other task forces in the state, and nobody else had problems with insurance.

“But it kept our guys off the streets. At the end of two weeks, Gary Arnold determined the insurance was okay.”

A second shut-down occurred when Duffey fired one of her six investigators. While she has high praise for the other five agents who signed on with the drug task force, Duffey says that one man, James Lovett, proved incompetent to the point of obstruction.

She fired Lovett, she says, after an incident when he was supposed to be staking out an undercover drug buy with another agent and he left the scene to buy a case of beer. The suspect arrived while Lovett was gone, placing both the agent’ s partner and the operation in jeopardy.

Duffey claims that as a result of her firing of Lovett, the task force was shut down “periodically” during the next two months, while the board considered Lovett’s appeal. While Lovett did not dispute he left the scene to buy beer, he said the action didn’t warrant firing, and he also alleged Duffey had fired him because he had refused to have sex with her, which she denies.

The beer incident had happened in June. The board discussed the matter until September, when it finally affirmed Duffey’ s firing of Lovett. The delay had kept the young task force from being fully operational for another two months.

Despite those obstacles, and without trying, Duffey and her team were piecing together a picture of what she now describes as “public officials involved in drug trafficking.”

“To what extent, I didn’t know,” she says. “And how it was all connected, I didn’t know . It’s impossible to get in and figure out the structure of an operation in the small amount of time I was there. And in the small amount of time I was there, we kept getting shut down.

“At the time, I couldn’t understand why we kept getting shut down for such ridiculous reasons. But now I understand. They didn’t want us operating.”

The coup de grace fell in September. After learning that the task force had been charged for 35 bank overdrafts, that state and federal financial reports had been filed late, and that her agents had been having trouble getting expenses reimbursed, Duffey says she began checking up on the records being kept by her financial officer, Kathy Evans.

After her own, secret audit of the books, Duffey says she reported to Gary Arnold that she’d found several discrepancies, including checks made out only to “cash,” and instances in which Duffey’s name had been forged. Arnold called the Arkansas State Police and asked them to investigate.

That investigation disclosed that Evans had indeed forged Duffey’s name to checks; that she had charged more than $300 in personal long distance phone calls to the task force; and that she had rented a car one weekend and charged it to the task force account. There was no information in the investigative report linking Duffey to any of the unaccounted-for $4,000 or to any financial misdeeds.

As to the area of task force operations over which Duffey exercised direct control, a state police investigator noted: “All evidence was accounted for in accordance with the evidence log, crime lab sheet, and case files.”

Despite those findings, the final state police report that was sent to the task force’s board left the question of blame for the missing funds unresolved, reporting its investigation as having been “inconclusive.”

Meanwhile, the task force was again shut down. ‘There was no rationale for our investigators not to be going out while the state police were investigating the books,” Duffey said. “We weren’t accused of mishandling any evidence. But that was Gary Arnold’s decision. He said, ‘Give them a paid vacation while this is going on.'”

Duffey was coming under personal pressure as well. At the same time the state police were checking the task force’s books, someone reported Duffey to state child-welfare officials for suspected abuse of her children. She says it was the lowest blow leveled against her in an increasingly nasty vendetta. The report was checked out, and a case-worker filed a report in October stating that, “there was no credible evidence of abuse or neglect.”

There were other allegations, too, and some of them were partly true. Duffey learned that her daughter, who was 17 at the time, had been provided with a false drivers license, showing her age as 21, that had been authorized through Duffey’ s office by Evans. (Drug task force officials are allowed to request fake IDs for under-cover officers .) When Duffey learned of the incident, she says she reported both Evans and her daughter to the state police. Neither was ever prosecuted.

In another instance, Duffey was criticized for allowing a county work-release prisoner to work for her husband’s moving company and on occasion slept in the basement at her family’s home. That did happen, and the impropriety was widely reported. What was not reported, Duffey claims, is that the trustee was also working as an informant for the drug task force and that the arrangement for him to work for Duffey’s husband had been approved by Sheriff Davis.

By this time, however, in the fall of 1990, the accumulation of accusations and innuendos against Duffey, however unsubstantiated, had achieved a critical mass. On Nov. 9, the board voted unanimously to fire her. It cited as its reasons the task force’s financial problems, Duffey’s “failure to heed warnings to avoid confrontations with individual board members,” and “a consensus opinion” that Duffey could “no longer achieve task force goals.”

Except for the resignation by her undercover officers, Duffey received almost no public support, other than her family. Nor did she help herself by speaking out at the time.

Today, she says the reason for her silence was that Govar at the U.S. attorney’s office kept assuring her that indictments resulting from the federal investigation and from information her office had provided it were imminent. She says she remained quiet believing that Harmon and others responsible for what she calls “the bludgeoning” she was receiving in the press were about to be brought to justice and that to talk about the alleged pending indictments might jeopardize them. When they came, she believed, so would her vindication.

But again, Duffey’s expectation proved wrong. In December 1990, one month after she was fired, U.S. Attorney Chuck Banks removed Govar from the Saline County corruption investigation. Though the investigation supposedly continued, the indictments Duffey says she’d been led to believe were imminent were not brought before the federal grand jury.

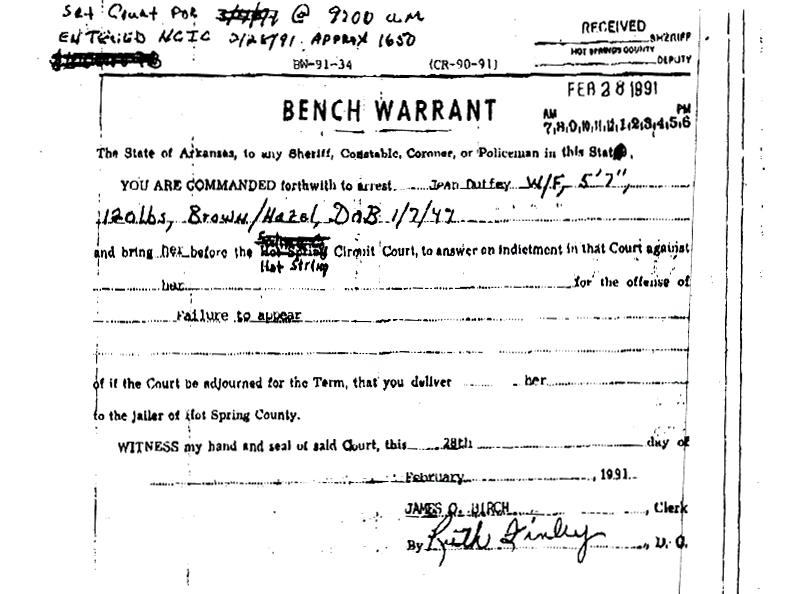

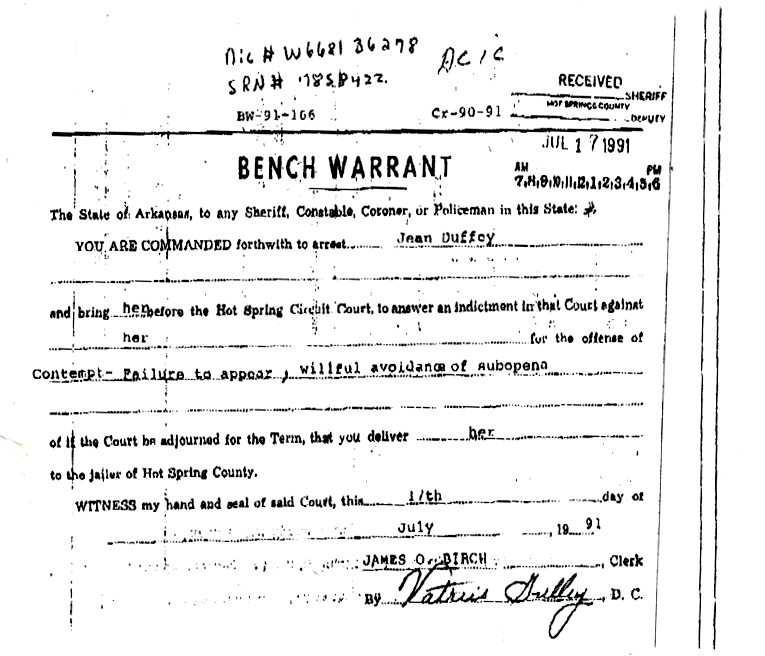

In January 1991, Harmon took over as prosecutor. One of the first things he did was to summon his own grand jury to investigate corruption in Saline County. He subpoenaed Duffey to testify.

“When I heard about the subpoena, I called Bob Govar and asked him what I should do regarding the information I’d passed on to the U.S. attorney’s office. He said I should ask Chuck Banks to file a motion to excuse me from testifying before a county grand jury because it could conflict with a federal investigation.”

Duffey says she went to Banks with that request. She says of that conversation, “Chuck Banks told me to tell Harmon and his grand jury everything I knew.”

Duffey says that at that point she figured she had three options. “One: I could have gone and turned over to Dan everything I had on him and other public officials. I believe doing that would have jeopardized the safety of every one of the almost 30 witnesses who had provided statements against those people. So I wasn’t going to give them that information.

“Two: I could have appeared and refused to give the information, at which point I would have been held in contempt of court and jailed. I didn’t consider that an option because, at that point, I was concerned about my safety.

“My third alternative was to just not go— which is what I chose. I went into hiding and avoided being served with the subpoena. So I was charged with failure to appear. That’s an unclassified misdemeanor, the lowest level of misdemeanor there is . But a felony warrant was issued for my arrest. Judge [John] Cole called me a fugitive in a statement to the Arkansas Democrat.”

Duffey says she’s still amazed by the fury of the attacks that were leveled against her and her office. But she says she understands why the volleys came with such intensity.

“They could have just sat still and quietly let me go away on Dec. 31, as I’d said from the beginning I planned to do. But we were building cases, so I had to be discredited. Everything we did had to be discredited. And it was.”

In June 1991, Banks announced that all the allegations his office had investigated against public officials in Saline County “were based on rumors and innuendo and didn’t have merit.” As a result, he said, no indictments would be sought.

Two months later, in August, Banks announced that Harmon would be charged with failure to file income tax returns for four years, from 1985 through 1988. When Harmon appeared in federal court to plead innocent to the four charges, he was told that, under federal law, in order to be released, he would have to submit to a drug test by urinalysis.

Harmon refused, complaining that the requirement violated his civil rights. He was subsequently jailed for 18 days.

Harmon’s personal grand jury investigation into possible official wrong-doing in his district never uncovered any mischief, either.

Duffey and her family eventually moved to Houston, where she now teaches high school algebra. This month she will be back in Arkansas for a trial that stems back to 1990 and to her chaotic stint as the drug task force administrator for Arkansas’s 7th Judicial District.

The upcoming trial is only remotely related to that job, however. It involves an exchange student from Norway who had been living with the exchange program’s coordinator in Hot Spring County, a woman named Kathy Fitzmaurice.

When the student left Fltzmaurice, alleging that Fitzmaurice had been taking money the student’s parents had been sending her from Norway, she was taken in by Duffey’s parents. Duffey became involved when she as a prosecutor signed a warrant to have Fitzmaurice arrested for allegedly taking the student’s money, an action Duffey says resulted in the restitution of some of the student’ s money.

Fitzmaurice later sued Duffey-for false arrest over the incident. Now that the case is about to reach court, Duffey says she’s looking forward to what will be brought out at the trial.

.Moreover, she says, she’s enjoying, for a change, seeing the public spotlight turned on Dan Harmon and on her successor at the drug task force, Roger Walls. The more their credibility is questioned, she figures, the better hers begins to look.

“I would like very much for my name to be cleared,” Duffey says. “Particularly for my family’s sake.

“The reason I did not speak out before was that I did not want to jeopardize what I thought was a competent federal investigation. If I’d started answering allegations and discussing why Dan Harmon was brutalizing me in the press, I would have had to explain I had gathered information on him through the drug task force.

“At the time, Govar was telling us that indictments would be coming ‘any day.’ But, of course, that never happened.

“I’m talking now because I think it’s getting pretty obvious to the public that there are [some] elected officials in the 7th Judicial District who are involved in drugs. I hope the public will start asking questions as to why the federal investigation was shut down— especially when the feds have known about illegal activities going on in this district for years.

“I was fired because our task force was uncovering information on public officials,” Duffey said. “There is supposed to be a federal investigation going on, so I’m not going to spout off about who’s doing what.”

Harmon on Duffey:

“SHE’S CERTIFIABLE”

Prosecuting Attorney Dan Harmon of Benton had this to say about Jean Duffey’s allegation he and other 7th Judicial District public officials are involved in drug use and drug-trafficking: “Ms. Duffey is insane.”

“Ms. Duffey is like most animal activists,” Harmon said in a recent telephone interview. “She’s a nut.”

Harmon said the complaints Duffey raises are not new allegations, and he said former U.S. Attorney Chuck Banks had investigated the allegations previously and found them false.

“If there had been anything there, Chuck Banks would have pursued them,” Harmon said. “Everybody’s corrupt, according to her, from the mailman on down.

“These are the same things she raised before,” Harmon said. “She’s certifiable.”

Harmon said there was “absolutely not” any truth to Duffey’s charges that public officials in the 7th Judicial District have been associated with drugs or that any investigation was hindered to protect them.

Harmon said he blames Duffey for the 7th Judicial District Drug Task Force’s troubled start, saying she exercised such loose control over the task force and undercover officers that problems were inevitable.

“I cleaned house,” Harmon said. “It was a real mess.”

Harmon noted that there is an outstanding warrant on Duffey since she did not appear in 1991 to testify before a Saline County grand jury.

“Ms. Duffey is not above the law,” he said.

Harmon’s predecessor and Duffey’s former boss—Gary Arnold, now a circuit chancery judge for the 7th Judicial District—had no comment on Duffey’s contentions.

“I’m just not going to comment,” Arnold said.

U.S. Attorney Paula Casey said her office normally does not confirm, deny or comment on investigations. “Obviously, there is an ongoing investigation. I can’t discuss the parameters.”

Neither Banks nor Assistant U.S. Attorney Robert Govar responded to requests for interviews.

Reproduced with permission

Copyright © 1996 Arkansas Writers’ Project, Inc. All Rights Reserved

January 8, 1996

News Release

From: Jean Duffey

Inserted in the above referenced Times article about corruption in Saline County, Dan Harmon rants about me being the one responsible for all the allegations against public officials back in 1990 and now. The truth is…I have never initiated any investigation and certainly have had nothing to do with the present investigation confirmed as “ongoing” by U. S. Attorney Paula Casey. No one in his right mind could believe I have the kind of influence to keep an investigation going for more than five years. Further, if “there is nothing there,” as Harmon claims, why has public official corruption in Saline County been the target of state and federal investigators for years?

Hopefully for the sake of the good people of Saline County, a federal grand jury will finally get to hear the evidence that has amassed over the years, and those jurors will be allowed to determine, on their own, the extent of corruption in Saline County. Such was not the case for the 1990 jurors when Chuck Banks shut down that grand jury investigation, declaring that allegations of corruption against Saline County officials had no merit. Three grand jurors were so angered by the shut down, they got word to me that they were unanimously ready to indict Harmon and others but were dismissed before getting to do so.

Interestingly, there have been several Saline County investigations shut down, including the investigation of drug trafficking by city officials as reported by the Arkansas Democrat on December 3, 1988. That “joint investigation by the FBI and the Arkansas State Police” also went nowhere. The public and the media should be demanding an answer to an alarming question: Who has the power to shut these investigations down, and why do they have an interest in protecting Saline County Officials.

NOTE: I appreciate the Arkansas Times for keeping a promise made to me five years ago. I was invited to come to them whenever I was ready to respond to the massive media campaign (more than 200 newspaper articles) launched against me by Dan Harmon in 1990. I did not respond at the time, because I depended on “justice to prevail” so my name would be cleared, but I won’t rely on that happening this time.

The Rise and Demise of Jean Duffey’s Task Force

By Jean Duffey

After attending graduate school at Texas A&M on the G.I. Bill, my husband, Duff, bought my dad’s moving company out of Hot Spring County, Arkansas. Duff built the business up around the Little Rock area, and in 1984, when I started law school in Little Rock, we moved to Saline County. During my second year of law school, I clerked for the City of Little Rock and stayed on as an assistant city attorney after graduation. In the summer of 1988, Dan Harmon called and asked if he and Richard Garrett could come to my home one Sunday morning. They came over to ask if I would work for Garrett if he was elected prosecutor of the Seventh Judicial District made up of Saline, Hot Spring, and Grant County. I gladly accepted the offer since it was a part-time job and the office was ten minutes from home. When Gary Arnold won the election instead of Garrett, Arnold called and offered me the same position. I was puzzled about that until I learned how the district’s “good old boys” crisscrossed party lines. I still don’t understand why I was asked to come on board, but it wasn’t long until they regretted doing so.

On January 1, 1989, Gary Arnold took office I was assigned to prosecute primarily in Saline County. I immediately clashed with a municipal judge and several Saline County defense attorneys, including Harmon, because I disrupted their way of taking care of DWI’s. I had heard rumors that $2000 would make a DWI “go away,” and with a percentage of DWI-convictions in the fifty to sixty percentile in previous years, it looked like several defendants came up with the cash. Ray Baxter, dubbed one of the county’s most prominent “good old boys,” is a Saline County defense attorney. After losing a DWI trial for one of his clients, Baxter was red-faced and outraged. He assured me I would be gone within six months. I survived though, and by the end of six months, the DWI conviction rate was in the ninety percentile. Teresa Harmon, one of Dan Harmon’s ex-wives, told me Harmon particularly hated me because he was the one who invited me into Saline County and I betrayed him.

Gary Arnold took heat over me, but he was initially supportive because I was popular with other county officials. Thousands of dollars in fines and court costs were pouring into the county treasury instead of lawyers’ pockets. Also, the law enforcement officers and victims of crimes were pleased to have an advocate – something they weren’t used to. Arnold told me I made him “look good.”

In March of 1990, Arnold’s office received federal and state funding to set up a drug task force in our district. The Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration (DFA) sent Arnold a formal notification letter on April 16, 1990 which served as a contract between Arnold and DFA. Page one of the letter verifies the official date the Seventh Judicial District Drug Task Force was established, and page two verifies Arnold’s contractual obligations. Arnold appointed the heads of the district’s eight largest law enforcement agencies to serve on the task force board, and one of them approached me about taking the job as administrator. I declined twice, but the board was not satisfied with any of the applicants and finally talked me into accepting. This was, however, in spite of Arnold’s protests.

Arnold, who was holding his first public office, had higher political ambitions and had obviously become one of the “good old boys.” The district’s politically prestigious Circuit Court Judge John Cole made it clear he was opposed to my appointment, calling me “dangerous” according to Robert Shepherd, the state drug czar at that time. Arnold vehemently argued to the board against me, but the other seven members ignored him and unanimously voted to hire me.

The very day the board made my appointment official, Gary Arnold walked into my office, stood in front of my desk, looked straight through me when I glanced up, and said matter-of-factly, “Jean, you are not to use the drug task force to investigate any public official.” He turned on his heel and left my office. I recently reflected back on that incident and was frankly amazed I was rather blase` about Arnold’s directive. My indifferent attitude stemmed from being conditioned to Arnold’s sometimes crass behavior and illogical ideas when such a directive from him would not have been at all surprising. Then I recalled the time I wanted to prosecute a rape case after interviewing the victim.

I regularly prosecuted all municipal and juvenile cases and their appeals, but had to be specifically assigned any felony case by Arnold. When I asked him if I could file charges and prosecute the rapist, he immediately said, “absolutely not” and gave no further explanation until I pressed him. He jumped up from behind his desk and said, “Go get me an empty coke bottle.” I looked confused and he repeated his command, so I went to the office break room, got the bottle, and started back to his office, but he met me in our secretary’s office. He took the bottle, held it out toward me, started wiggling it around, and said, “now try to stick your finger in the hole.” I said, “Gary, what is your point?” He said, “It’s hard to hit a moving target. It takes cooperation from the female.” I was disgusted that he was our district prosecutor and my boss. Still I thought he refused to allow me to file the charges because the rapist was the victim’s ex-boyfriend and the case would be too hard to prosecute. However, a couple of years later, my feelings became even more cynical toward Arnold’s sentiment about any rape case.

In December of 1990, Arnold dropped the ball in a case where a 16-year-old deaf girl was raped by the 37-year-old son of a court reporter. The circumstances of that case was reported by The Benton Courier in a September 6, 1991 article Stuart’s DNA matched that in the semen found on the little girl, which positively identified Stuart as the rapist. Arnold, however, did not provide the DNA test results to Stuart’s defense attorney in time for proper trial preparation, so the case was dismissed. That unfortunate slip-up might be forgiven under circumstances where the prosecutor was working under a time-crunch deadline, but in this case, Arnold had two years to comply – TWO YEARS! This was either gross incompetence or dirty dealing , and in my opinion, either or both are plausible explanations for Arnold letting this rapist get off.

I knew he was anxious to please the district’s political hierarchy, but it still came as a surprise when I realized he was doing everything he could to cause me to fail as task force director. Those who remember the media smear campaign against me will recall Dan Harmon was the source of the hateful and viscous lies being printed. That is a matter of public record. However, Gary Arnold’s insidious role in discrediting me made the battle to survive a losing one from the beginning.

It all started immediately after Arnold was unanimously over-ruled by the board and I was appointed task force administrator. Within a few days, Arnold sent me to an in-service meeting at the State Department of Finance and Administration to learn how to set up the books. Gordon Burton, Grants Administration Director, sent me back to Saline County with a message for Arnold that it was not possible for me to be the administrator and keep the books. Being task force administrator was a full-time job in itself, and then some.

According to DFA Administrator Jerry Duran, most task forces have a public agency with the city or county to keep the books, but for some reason, Arnold directed me to find a task force fiscal officer. Since this officer would be hired by the board and would be answerable to the board, I didn’t understand why Arnold was saddling me with the responsibility. He didn’t even let me know if he had given a public notice for the job vacancy, and he rejected the only suggestion I had. After a couple of weeks, I was approached by a court clerk who insisted her daughter, Kathy Evans, would be ideal. I submitted Evans’ name to Arnold and she was hired. Apparently, Arnold set me up to be the one who recommended Evans who was later discovered by my officers and I to be a “plant.”

Evans’ duties were to set up task force books, keep all the financial records, and manage the task force money. She went to a training workshop and was given charge of task force funds. Evans’ name appeared on the task force letter head stationery along with mine, and we were directly answerable to the board for our duties; not to each other. I was in charge of investigations and prosecutions of drug cases developed by the task force. I hired three full-time and four part-time undercover officers who were directly answerable to me. By the first of May, we were up and running.

Arnold was, by now, well established with the local political machine and was set up to run unopposed as a republican for a judgeship. Dan Harmon was set up to run unopposed as a democrat to take over Arnold’s position as prosecuting attorney. By June, Arnold was officially juvenile judge-elect and Harmon was officially the prosecutor-elect. By that time, however, my task force investigators had uncovered substantial evidence linking Harmon to local drug trafficking, so it was no surprise when Harmon launched a media smear campaign against me and my task force. And perhaps, he was also seeking revenge for my “betraying” his invitation to join the “good old boys” of Saline County.

The media’s cooperation with Harmon was startling. Back in 1988, Harmon cultivated the media while he was heading the county grand jury investigation of the “train deaths.” Circuit Judge John Cole appointed Harmon special prosecutor which gave him immediate access to and control of information as it developed. This, of course, is when witnesses began turning up dead, but no one connected that to Harmon at the time. Harmon also controlled the information that went out to the public through the media. He is a masterful manipulator and used a gullible media to make himself a folk hero for his hard work and dedication to the case. To this day, two of the reporters have not abandoned their support of Dan Harmon. They are Lynda Hollenbeck with the Benton Courier and Doug Thompson with the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. (In 1990, Thompson wrote for the Democrat which bought out the Gazette in 1991.) Hollenbeck and Thompson were willing participants in Harmon’s smear campaign against me and my task force and neither reporter bothered to verify anything Harmon said; they just printed it – lie after lie, article after article – even when they knew Harmon was lying.

At first, I wasn’t too concerned about the negative publicity, because I was taking the information about Harmon and other public officials involved in drugs to Assistant U.S. Attorney Bob Govar. Govar had headed a grand jury probe into public official corruption in Saline County for a year, and the information my task force took him made his case stronger. Govar repeatedly assured me that indictments against Dan Harmon and other Saline County public officials were imminent. However, according to Govar, his boss, Chuck Banks, was holding him back even though Govar insisted he was ready to ask the grand jury for indictments and the grand jury was ready to give them. Govar was eventually removed from the investigation by Banks who took over and dismantled it. By December of 1990, I had been so discredited and brutalized by the media, Banks used me to justify shutting down Govar’s nearly two-year-long investigation. Bank’s held a news conference on June 27, 1991, and cleared “Harmon, his family and all Saline County public officials . . . of allegations of drug-related public misconduct and other forms of wrongdoing.” The Arkansas Gazette goes on to report Banks saying the allegations were based on rumors and innuendo and didn’t have merit. The article then quotes Harmon; “I regret . . . federal investigators listened to a crazy person like Jean Duffey.” Arkansas Gazette, June 28, 1991. The details of Govar’s investigation and Banks’ part in protecting Saline County officials from prosecution is the subject of The 1990 Federal Grand Jury Investigation. The part the media played in protecting Dan Harmon and other public officials is included in that report.

If I had known the smear campaign was going to be used by Banks to protect the public officials we investigated, I would not have sat back and depended on the promised federal indictments to clear my name. If I had it to do again, I would have aggressively defended myself against every lie from the very first article which was written by Doug Thompson the day after Dan Harmon became prosecutor-elect. Thompson reported Harmon saying, “There are more serious crimes than neglecting or abuse of an animal, yet that’s what she’d rather spend time prosecuting.” (He was, of course, referring to me.) Thompson called me for a response and I told him to simply check the municipal court dockets. Of the hundreds of cases I prosecuted, only two were animal related cases. Thompson, however, didn’t report my response or what the municipal court records clearly showed. Instead, he reported that I had founded the animal rights organization, Arkansas For Animals, which insinuated Harmon’s accusation was true. Thompson then reported Harmon’s further accusations that I “wasted task force money on automatic rifles and surveillance equipment that might be nice in New York City, but is not essential in rural Arkansas.” The truth is, our task force did not use weapons of any kind, and although we bought the bare essential surveillance equipment, most of what we needed was loaned to us by the Malvern Police Department. The equipment we did purchase was budgeted for and justified by Gary Arnold in his original application for funding that was approved by DFA. I showed Thompson the records, but he wasn’t interested in reporting the truth. He, in fact, reported, “Duffey, who was out of town on task force business Wednesday, could not be reached for comment” which was an outright, blatant lie. He did reach me, I did comment, and he lied about it. Arkansas Democrat, June 1, 1990. And so it went. That article was the first of an incredible string of irresponsible and unethical reporting by Thompson and Hollenbeck and outright lying by Thompson. I had always believed “truth is a defense against slander,” but the truth doesn’t help you if you can’t get it reported.

Hollenbeck and Thompson were not the only people Harmon manipulated. In September, I got a tip that the task force fiscal officer, Kathy Evans, and her mother had been meeting with Harmon. Early on, my task force officers were suspicious of Evans. She “snooped” into files and listened to conversations that didn’t have anything to do with her job. Evans did not have access to any reports or files on public officials since my officers and I decided to keep all such records away from the task force office. We turned everything over to Bob Govar for his federal grand jury investigation.

After investigating the tip about Evans, I learned Harmon had put her up to over-drafting the task force bank account and to forging my name on task force checks. Evans had unrealistic romantic interests in one of my task force officers who I asked to call Evans and find out what he could. Evans confessed she was cooperating with Harmon and even admitted she and her mother were regularly meeting with him. Evans told my officer they would “soon have enough” to get rid of me and Evans said Harmon had promised her she would have my job as soon as he took office as prosecutor. According to Evans, Harmon also promised her mother a position in his office.

While I was clambering around for information, I learned Evans used task force authorization to obtain fake driver’s licenses for herself and for my 17-year-old daughter. This was a misdemeanor criminal offense, which I reported to the Arkansas State Police and used it as an excuse to suspend Evans from the task force office. I took all of the fiscal files, books, and records I could find to the state prosecutor coordinator’s office, which immediately began helping us reconstruct the task force finances. After the state police interviewed me and they had already begun an investigation, Arnold wrote a letter requesting “an investigation by the Arkansas State Police as soon as possible.” He wrote, “a review of the financial records . . . by the Office of Intergovernmental Services indicates the possibility of theft, or at least unauthorized expenditures of Task Force funds.” Arnold, of course, did not bother to mention that I was the one who discovered the problem and that I had already taken steps to correct the situation and that I had already been talking with state police investigators. And, of course, he did not mention that Evans was under his direct supervision, not mine, or that he was directly responsible for confidential expenditures, not me. Evans had forged my signature to checks in the amount of nearly $4000 which had been cashed for confidential expenditures and drug buys. However, there was no record of the money after the checks were cashed. Arnold was directly accountable for the disbursement of these funds, and in fact, it was his signature on the Confidential Funds Certification, not mine. Yet, I was the one who was linked time after time in the media to “the missing $4000,” not Evans and not Arnold.

Arnold came to the prosecutor coordinator’ office the day I took the financial records up to be reconstructed. He was agitated, nervous, and rude. He was desperate to put the blame for Evans’ actions on me. Evans was claiming I told her to forge my name on those checks, which was as ridiculous, but not as absurd as Arnold ordering me to call Doug Thompson to tell him I authorized the overdrafts. I had asked for authorization for the bank to overdraft our very first check before our funding arrived so we could begin operating, but that was the one and only time I requested an overdraft and that was done in advance and with board approval. I was outraged at Arnold’s desperation and never had another civil conversation with him. It hit me like a ton of bricks, at that moment, Gary Arnold was doing more to destroy me than was Dan Harmon. I later saw Arnold explaining to Doug Thompson that the board was changing the structure of the task force. Arnold said they were hiring a field supervisor to be in charge of the officers and I would be in charge of the fiscal officer. That was such a stupid attempt to put the blame on me retroactively even Thompson didn’t print it.

I then began putting together all the things Arnold had done to hinder and discredit me and feed the media. He kept coming up with ridiculous reasons to shut down the task force weeks at a time. The first time was very early on when he claimed he wanted “to check if the task force officers have proper liability coverage.” My officers had been sworn in as deputy sheriff’s in the district and were covered under the sheriff departments’ insurance programs, which was the recommended procedure and was just how other task forces were insuring their officers. Arnold kept dragging his feet and finally, after two weeks, he allowed us to work again. He told me he was satisfied that our liability coverage was adequate, but he showed me no evidence whatsoever that he had done any research or checking on it during the two-week period he wouldn’t allow my officers to be on the streets. The next time Arnold shut us down was off and on for nearly a month after I fired one of my officers, Jim Lovette, for gross incompetence and negligence of duty documented in a two-page letter to Lovette’s personnel file (page 1 and page 2). The board upheld Lovette’s termination, but only after Arnold had the board conduct an exhaustive investigation of all Lovette’s lies and ridiculous allegations against me. One of the board members told me they knew early on Lovette was lying. Not surprisingly, Lovette was frequently seen with Dan Harmon thereafter.

Arnold also did things that were very deliberate to discredit me. One incident happened at the August task force board meeting. One of the board members and I rode with Arnold to the meeting which was in Grant County. Arnold didn’t mentioned a memo he had gotten from DFA until the meeting was underway and Doug Thompson was perched on the edge of his seat, pad and pencil in hand. If it sounds like I am insinuating the incident was planned, orchestrated, and choreographed, that is exactly what I am insinuating. When the meeting turned to new business, Arnold yanked a letter-size paper from his folder, waved it violently in my face, and said, “Just what is this hate letter all about.” I, of course, didn’t have a clue what this “hate letter” was all about until I read the paper which was a memorandum from the Department of Finance and Administration. The memo stated the task force was in danger of losing funding because we were delinquent in submitting two reports. One of the delinquent reports was a progress report for which I had been given an extension, and the other was a budget report which Kathy Evans was responsible for filing, and I knew nothing about that one.

I suggested the board take a break while I phoned DFA which, obviously, is what Arnold should have done himself before the meeting. During the break, a DFA secretary located both the budget report and the extension on the progress report in a misplaced file folder. When I explained DFA had sent the memo by mistake, Arnold was noticeably disappointed. Perhaps Doug Thompson was disappointed that he couldn’t use the so-called “hate letter” against me at that time, but he found a way to use it a month later by referring to it out of context and leaving off the part about the memo being sent in error. That entire article by Thompson is an amazing example of Thompson’s obvious attempt to discredit me with lies and twisted half truths. That article is discussed in detail in The State Police, the Media, and the Missing $4000.

The most devastating shut down was during the six-weeks-long investigation of task force finances by the state police. What should have been an investigation of Kathy Evans, was an investigation of every computer file, every paper file, every case record, every narcotics buy, every confidential informant report – every move my task force officers and I had ever made. This was no investigation of a fiscal officer who was stealing from the task force – this was clearly a snooping expedition that had nothing to do with fiscal misconduct. Fortunately, my task force officers and I were not keeping files on public officials at the task force office, so the state police did not find what they were looking for. Even though it was Arnold’s intentions to keep us from operating during those long weeks, my officers went right on working but were not given money to make drug buys. My officers stayed in touch with their informants and continued to develop new information. This was in spite of Arnold’s directive to them to “take a paid vacation.”

Arnold also used the investigation to provide the media with ammunition – Doug Thompson in particular. Arnold ordered me to not speak with the media, yet he was more than cooperative in providing them with information that sometimes needed explanations, and I was not allowed to give it. For example, under Freedom of Information, (FOI) Thompson got a copy of a report talking about Lovette’s botched drug surveillance buy. The report had Lovette’s name blacked out, and Thompson reported the incident without explaining I had already fired Lovette for his conduct. Thompson’s report insinuated I still had this officer working for me.

Speaking of FOI, I found it interesting when the district’s state senator, Charlie Cole Chaffin, expedited an opinion from the state attorney general to determine if Doug Thompson and other reporters could attend task force board meetings. Chaffin is Circuit Judge John Cole’s sister and a long-time and enthusiastic supporter of Dan Harmon. In 1991, Harmon was jailed by a federal judge for refusing to submit to a drug test as a standard condition for release after a plea appearance on federal tax charges. Chaffin rallied to Harmon’s defense and gave him a public cheer while she was speaking at the opening of a community center. Although the Benton Courier article of September 7, 1991, makes it sound like several hundred people cheered for Harmon, the truth is the crowd responded to Chaffin’s enthusiasm for the Constitution. When Chaffin mentioned Harmon, there was less response from the crowd. This article is typical of how politicians and the media manipulate the public.

The state police investigation of the task force finances was such an incredible sham, it is a story all to itself and is the subject of The State Police, the Media, and the Missing $4000. The story includes documents from the investigation including Evans’ interview in which she admits to forging my signature on checks amounting to the missing funds. After a six-weeks-long investigation where there is an admission, documentation, and corroboration that Kathy Evans was stealing from the task force, the state police claims its investigation was “inconclusive.” Bottom line – the investigation did not turn up a hint of any illegal or improper action on my part, so their investigation was a wash. Evans was not prosecuted for anything, not even for illegally obtaining fake driver’s license for herself and my daughter. Since Evans was clearly being protected from prosecution, my daughter was also not prosecuted. I’m sure otherwise, she would have been charged and it would have made headlines. The state police investigation of my task force is typical of how the state police has participated in covering up Saline County corruption. A 2000-page state police file is the subject of The State Police Investigation and reveals their participation in that cover-up.

It is absolutely amazing to me now to look back and realize the things my task force officers and I were able to accomplish in the short time we were allowed to operate and under such adverse circumstances. We linked Dan Harmon and other public officials in the Seventh Judicial District to the source of much of the drug trade, but we were never allowed to present the evidence to the federal grand jury. I was fired as task force administrator and deputy prosecutor on November 9, Arnold sent me a letter of termination on November 16, 1990, stating “the basis for termination was unsatisfactory performance.” Actually, the incredible amount of adverse publicity was what the board discussed as the reason I was being fired. The board members felt I had “become ineffective” because of the media smear campaign. “Unsatisfactory performance” was Arnold’s words. Arnold goes on to cite all the financial problems as “among the reasons cited by one or more board members” for my termination, but was careful to say “not all board members voiced all the reasons listed.” I, in fact, don’t recall any board member other than Arnold who thought I was responsible for Evans’ actions. Additionally, Arnold includes “failure to avoid confrontations with individual board members” as a reason for being fired. Besides being confrontational with Arnold, I had words with Saline County Sheriff Larry Davis, who later became one of Dan Harmon’s task force officers, and with Hot Spring County Sheriff Doyle Cook, who quit the board when he found out my task force was investigating him. The details of Davis and Cook are in The 1990 Federal Grand Jury Investigation. The reasons for having confrontations with Arnold, Davis, and Cook were obviously because they were in conflict with the task force doing its job, and I refused to pretend otherwise.

Gary Arnold has been the Seventh Judicial District Juvenile Judge since January 1, 1991. Of all the elected positions, a juvenile judgeship is the worst position for an incompetent or corrupt official to hold because the proceedings are closed to the public. I hope the people of the district will encourage someone with integrity to run against Arnold in the next elections for juvenile judge which, unfortunately, will not be for another two years. Gary Arnold is only one of the elected officials who need to be voted out of office, but you begin a journey by taking one step at a time. The voters of Saline County had the opportunity to rid itself of Dan Harmon this past May, by handing him a resounding defeat. That was a good first step.

© Jean Duffey 1996

Jean's Arrest Warrants 1991

Bond Denied If Duffey Caught