By Mara Leveritt

"Big hole!" The second the headlight picked up the forms, the three men in the lead engine shot from their, seats, straining forward. The engineer yelled, "Oh, my God!" Instantly, the men threw the train into emergency--the big hole on the brake--a maneuver that risked derailing. The engineer hit the horn. He never let up, nor did he take his eyes off the motionless figures, from the moment he saw them until the body of the second boy slipped placidly under his screaming machine.

Later, the engineer would describe for police the boys' apparent calm. As the train bore down on them, he said they looked as relaxed as "boys sunbathing on the beach."

The men stopped the north-bound, mile-long train, and the conductor radioed his dispatcher. He reported their location: just past the Shobe Road crossing at Alexander, almost precisely on the Pulaski-Saline county line. Then the crewmen climbed off the engine. Flashlights scanning, they walked back to the horror that waited. It was 4:45 in the morning, August 23, 1987.

Although the site was difficult to reach--a trestle bounded on either side by woods--Deputy Kathy Carty of the Saline County Sheriff's Office, and Larry Davis, a reserve deputy who would later become sheriff, arrived at the scene within minutes. They were soon joined by Deputy Chuck Tallent, and then Ray Richmond, of the office's criminal investigation division, who took command of the scene. It was a nightmare, but in many ways, what was about to happen was more frightening still. Beginning almost immediately, through ignorance, laziness, or worse, crucial information that might have explained the deaths was either lost, overlooked, misinterpreted, or removed entirely from the scene; the destruction of the case began.

It was a dark, moonless morning. Because of the powerful light on the Union Pacific freight train, the men in the engine were able to provide investigators with detailed information about what they'd seen in the awful seconds before impact.

Conductor Jerry H. Tomlin said the first thing they noticed was "something between the rails which appeared to be partially covered with a green tarp."

All three of the men reported seeing the cloth; all three reported that it was a faded green fabric, definitely not plastic. "The tarp was over the lower part of their legs," Tomlin reported, "probably down to about the knee and up to the upper part of the thigh ... l also noticed there was a gun approximately six inches to one foot away from the head of the boy farthest to the north. After the accident I observed that the tarp was at this time down beside the creek."

The other two men in the locomotive, James "Square" Shroyer, the engineer, and Danny De Lamar, the brakeman, also told deputies about having seen the tarp. More important, Tomlin says he pointed it out to Deputy Charles Tallent with his flashlight.

"lt was laying at the bulkhead of the bridge where we hit the boys," Tomlin would later tell the Arkansas State Police. "I was shining my light down off the bridge. I told the deputy--I believe his name was Tallent. I also told two or three other people out there, but nobody seemed to get it."

Engineer Shroyer later said he heard Tomlin tell Tallent about the tarp. Nonetheless, that crucial piece of evidence was never recovered; it disappeared and has never been seen again.

Four and a half years have passed. By now the missing tarp has become a metaphor for the events of that night and for the shroud of darkness that still covers them. In many ways, the mystery has expanded.

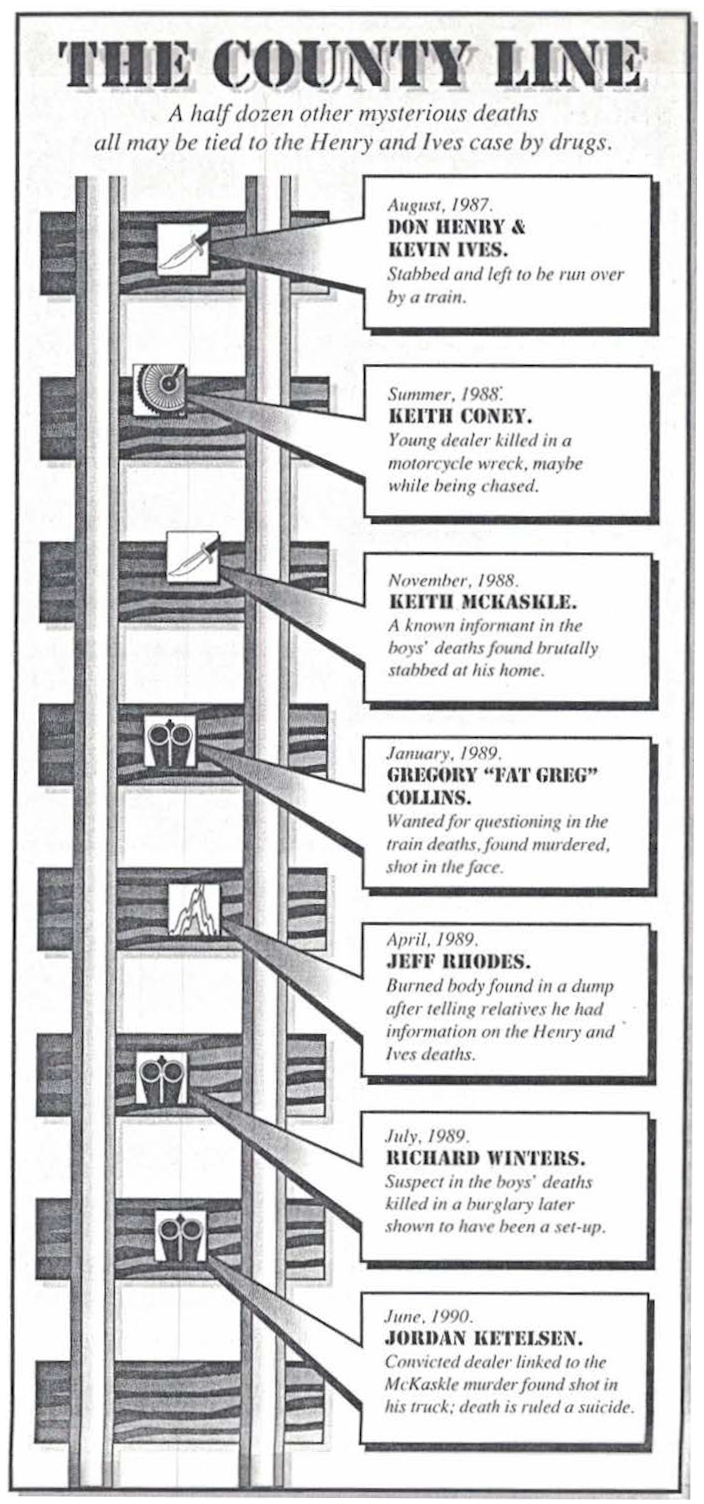

Since the night the two teenage boys, Don Henry and Kevin Ives, were found run over by the train, four men with indirect links to the case have met similarly violent fates. A fifth man, who police admit was working as an informant in the case, was found brutally stabbed to death. A sixth, implicated in the death of the informant, is said to have killed himself. And a seventh man, who disappeared four months after talking about the case to the state police, is either dead or hiding out.

The boys found on the tracks and the other men, dead or disappeared, had one thing in common. All were connected--some directly, some only indirectly--with the drug and burglary scene in Saline County. The boys struck by the train were found carrying a small amount of marijuana, they had casual contact with many people who witnesses later testified were using and selling harder drugs, and some testimony would develop suggesting that one of the boys may recently have begun dabbling in a small-scale sale of cocaine. Nonetheless, despite a prosecutor's hearing, the impaneling of a grand jury, a state police investigation, two episodes dealing with the case on NBC's "Unsolved Mysteries," and a federal grand jury probe into public corruption in Saline County, the mystery of the boys' deaths has never been solved nor effectively linked with the others that followed. The murderer or group of murderers who pulled the tarp over the bodies of Don Henry and Kevin Ives nearly five years ago still operate under a cloak of darkness today. The coverup of their case and others continues.

Curtis Henry is an electrician. In 1987 he lived with his wife and his son in a house trailer about 300 yards from the tracks, about a mile south of where the bodies were found. The night before the deaths, on August 22, Henry's son Don and Don's closest friend, Kevin Ives, had left the house on foot shortly after 12:30 to go hunting. They were supposed to have spent the night together at his house. By sunup they hadn't returned. Both their cars were still in the driveway.

Henry got in his own car and began searching for them. When he saw a deputy sheriff's car, he asked the officer if he'd seen the boys. Within an hour, Deputy Tallent arrived at the Henry house. Cautiously, he outlined the morning's events. "Was one of the boys wearing a camouflage hunting cap?" Henry asked. He was, Tallent said. " Like this?" Henry asked, producing one of his own. Grimly, Tallent nodded.

Kevin Ives had turned 17 in April. Don Henry's 17thbirthday was three weeks away.

Larry Ives, an engineer for Union Pacific, was in Poplar Bluff, Mo., the day of the deaths. The route there was a new one for him. Until just a few weeks before, Ives had been the engineer on the railroad's main run to Texas, the same line where his son was found killed. Shroyer was his replacement. Notified of the tragedy, Ives raced back to his wife Linda and their daugher Alicia in the home they had recently built in Bryant. Looking back, the family's location in Saline County would appear bitterly ironic; Larry and Linda Ives had moved there from Little Rock specifically to escape the drug-related violence associated with the bigger city

By now, Larry Ives has visited the trestle where his son's body was found a half dozen times, usually in the company of reporters. He now counts the question of the tarp as just one more of the tragedy's too many wearisome mysteries. He says he has tried to keep an open mind on the case, but there's a lot that's hard to swallow.

The deputies' response when they were questioned about the tarp later is one piece that Ives simply cannot choke down. They argued that the crew must have suffered an optical illusion, that the tarp had never existed. In all his years as an engineer, Ives says he has never seen anything on the tracks, day or night, that later turned out to be an optical illusion, and neither has any other engineer or crewman he knows.

"There's no question they could have seen it if it was there" Ives says looking aimlessly off the trestle. "I don't know where it went. That's the big question: Where did it go?"

Don Henry and Kevin Ives had been friends for about six months, but the first time their parents met was that hot August morning, when they were thrown together in grief. The ordeal! since then has taken its toll.

Stunned by gossip, Curtis Henry's daughter Gayla left to live with relatives in Florida soon after the deaths and has never returned. Her stepmother, Marvella Henry, has said little publicly about the case. But Curtis Henry has been articulate and vocal He keeps an active file on the case and still tries to follow leads,though he holds out little hope at this point that the mystery will be solved.

For Larry Ives, the challenge since Kevin's death has been mostly to endure. "You don't ever get over it" he says, "you just kind of live through it. I sought psychiatric help there for a while, and that kind of convinced me there is a future." To live in the present Ives says he has to let the past recede, so be tries not to embroil himself in the case.

Linda Ives, on the other hand, has taken the opposite approach to coping. When she began to have doubts about the way the investigation was being conducted, she converted Kevin's bedroom into an office, which she has since dubbed "the war room." She too has a list of questions she feels deserve to be answered.

The parents do not agree on all points, but they do agree on this: The investigation into their sons' deaths was bungled, it was bungled at the start, and it was probably bungled deliberately.

Curtis Henry has nothing but scorn for the way Saline County deputies

managed the

case. "It slipped through their fingers when it happened," he says.

"They never even considered the possibility of murder that morning. They

couldn't afford to get into a murder investigation because that would

uncover too many other things. I think if they had done a professional

job that morning that the murderers would be behind bars right now."

Marvella Henry says simply, "I think that several people were involved and that part of them were police."

Linda Ives focused her attention on Dr. Fahmy Malak, the longtime state medical examiner who recently resigned. She says Malak was supposed to be the safeguard, the one state official who could have reversed a faulty local ruling and put a derailed murder investigation back on course (Arkansas Times, June 1990). Instead, he further confounded the foul-up. Six months after the tragedy she told reporters, "Dr. Malak has made the nearly unbearable circumstance of my son's death even more intolerable ... "

Larry Ives deliberates a moment when asked why the investigation was fruitless. "I think the main reason we didn't get a thorough investigation to start with," he says, "is that there's a big drug ring operating in Saline County and a lot of people in the know are involved, and they didn't want an investigation because they thought it would mess up their little party.

It's a standard of law enforcement that any suspicious death is treated as a murder until that possibility is either established or eliminated, in order to assure that critical evidence is not lost. But in the case of the two Bryant teenagers, that fundamental rule was ignored.

For Curtis Henry, doubts about the investigators' competence-- and possibly their intentions--arose early. "When Chuck Tallent came out to my house and tried to tell me it was a suicide. I said, "That's crazy as hell." Don and I had sat out in the yard that very day and we'd talked about the deer season coming up and about building stands. Don Henry loved to hunt. There was no way he was thinking of killing himself. I told Tallent that. Then, when he saw that suicide wasn't going to fly, they only had one thing left, and that was drugs, and they leaned on them real heavy."The lvees also balked at the suggestion of suicide. "If Kevin had a problem, it was that he was too happy-go-lucky and out to have fun," his father recalls. "He could do good work, but we had to stay on him to make passing grades."

The parents would later learn that they were not the only ones to balk at the suggestion that the deaths were either suicides or accidental. Deputy Kathy Carty, who has since remarried and changed her name to Pearson, says she was astonished when Lt. Ray Richmond ordered deputies to handle the scene "like a traffic fatality," as a train-pedestrian accident. She recalls, 'I told the coroner, 'We either have two of he damnedest suicides I've ever seen here or we have a double homicide."

| Deputy Kathy Carty Pearson argued unsuccessfully

for treating the deaths as homicides ••• |

The ambulance crew also found evidence that struck them as suspicious. After· the event, in an unusual move, the two emergency medical technicians on the scene appended what they called a "note of interest" to the end of their official report. It read, "Blood from the bodies and on the body parts we observed was a dark color in nature. Due to our training, this would indicate lack of oxygen present in the blood and could pose a question as to how long the victims had been down/dead."

In the months that followed, reports would be leaked to the media that paperwork had already been prepared at the state medical examiner's office listing the boys' deaths as suicides, but that that cause of death was changed at the last minute. Instead of ruling the deaths suicides, Malak concluded the boys were "unconscious and in a deep sleep on the railroad tracks, under the psychedelic influence of marijuana," and that their deaths had therefore been accidental.

It was an incredible ruling--Linda Ives called it "asinine"--one that in the coming year would preoccupy the media, be refuted repeatedly by specialists, and over time become the laughingstock of ordinary citizens who knew firsthand the effects of marijuana.

On a more serious level, the ruling diverted attention at a crucial moment from the real questions of the case; chief among them, the apparently casual but lethal ties between the two dead boys and residents of Saline County who were dealing truly dangerous drugs, like cocaine and crystal methamphetamine. Worse still, it left to the boys' grief-stricken parents the job that properly belonged to the police and medical examiner--the horrible task of proving that their sons had not killed themselves and were not victims of an accident but that they had been murdered.

Marvella Henry says that in the first days after the death, Rick Elmendorf, the department's chief deputy at the time stopped by the house often. "He kept telling us, 'I sure hope Malak rules it an accident and not a suicide,' "she recalls."I thought that was strange. He never, ever mentioned the possibility of murder."

The autopsy report showing an absence of any other drug, including alcohol, in the boys' systems cemented her husband's disbelief. "When Malak said they were clean except for marijuana, I knew right then that that man is crazy," Curtis Henry says. "That ruling of his was what ended the investigation. It was a two-way deal. I think Sheriff [James] Steed screwed it up and Malak sealed it. Malak put the icing on the cake."

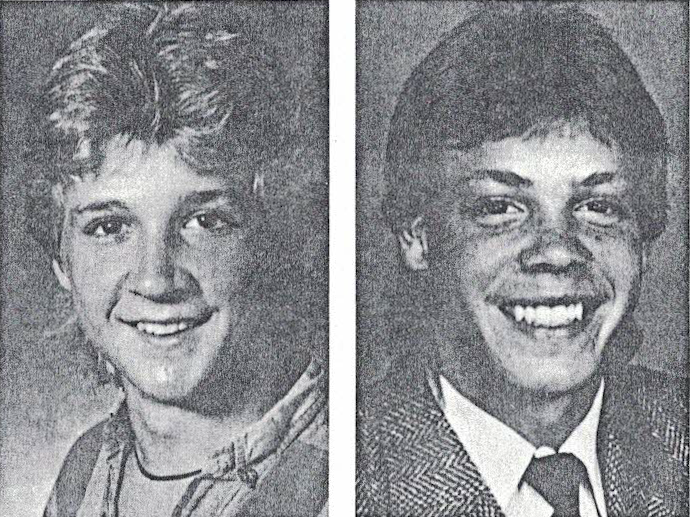

|

| State officials insisted Don

Henry (left) and Kevin Ives fell asleep on the tracks. |

Besides the parents' growing fears that the truth behind their sons' deaths might be being suppressed, they began to suspect they were also dealing with a remarkable degree of plain old police incompetence. It made a chilling combination. Consider what the Henrys and lvees were later to learn:

- When deputies completed their work at the tracks, part of one of the bodies--a foot--was left behind at the scene. Police retrieved the remains from where they remained on the tracks only after a cousin of one of the boys who'd visited the site reported the discovery.

- Not one, but two gold chains were also reportedly found by visitors to the scene after police had left. One of chains, on which the clasps were said to have been broken, was never recovered. Curtis Henry says the chain that was not recovered fit the description of one worn by his son Don; the origins of the other chain are not known.

- Nearly six months after the incident, the ambulance driver reported

at the

prosecutor's hearing that she had encountered three men in the woods near the tracks as she was trying to maneuver her ambulance to the site. Two of the men were in a pickup truck, one was on foot, but all three knew each other. They identified themselves as members of the Alexander Fire Department who'd heard the commotion and were trying to be of assistance. Soon after this information was brought forth, it also was learned that Alexander didn't have a fire department. - There was reportedly only one gun found at the scene, Don Henry's cherished .22, found lying beside him, bull shattered, on the tracks. Pearson, now a former deputy who is suing the department over several issues, some stemming from the handling of this case, says the weapon was bagged and sealed as evidence. But video footage taken by Little Rock television station KARK that morning shows an item in the truck where the bodies were loaded that appears to be the barrel of a rifle. It is not bagged, and is being casually examined by a man who's not in uniform, apparently a bystander. When shown the tape and asked about the item later, sheriffs officials said it was one of the deputies' long handled flashlights. Whether the item was Henry's rifle, another weapon, or a flashlight as deputies claimed, still remains unclear. What is known is that no ballistics tests were ever performed on the one rifle said to have been recovered whether it had been fired.

- In a move that was so dumb it has now become almost legendary, Tallent used the of end of the train as his point of reference in locating evidence in his report. When the train rolled away, the report was rendered worthless. But the mistake was more than laughable. Pearson and others believe that what was being covered up, at least in the early stages of this investigation, was not so much evidence of criminality as evidence of police stupidity.

- Even treating the deaths as accidents, though, it took hours to

remove the bodies and fill out the reports. During that time Sheriff

James Steed, the Saline County official responsible for the

investigation, never visited the scene. Nonetheless, he consistently

praised the way the investigation had been handled.

- Tests of the boys' clothing, which, through the presence or absence of foreign fibers, would have confirmed or laid to rest the mystery of the tarp, were never conducted. But the parents only found that out later. Early on, Linda Ives says. deputies told the parents that the clothing had been tested and that no fibers from a tarp had been found. When the boys' bodies were exhumed and a medical examiner from Atlanta reported evidence contradicting Malak's conclusions as to the cause of death, the Arkansas Sheriffs' Association did not complain about this latest blunder in what was emerging as a pattern of critical forensic foul ups. instead, after affirming their overwhelming support for Malak, the sheriffs hired an investigator to try to dig up some dirt on the physician who'd discredited him. The investigator was unsuccessful. "If they had read all my reports and attacked my findings. that would have been one thing,'' the Atlanta pathologist said. "But instead they tried to find something in my background. It's illogical."

|

| Deputies said the item being handled here was not a gun but a flashlight. |

The move was indeed illogical, unless one considers the sheriffs' political motives for keeping Malak in office. A compliant medical examiner who will rubber stamp local officials' findings as to causes of deaths in their jurisdictions hands local officials tremendous unchecked power. In a case like this, that kind of power could have squelched the investigation entirely--and almost did. If it hadn't been for the persistence of Don Henry's and Kevin Ives' parents, the boys' death would still be listed today as accident. Gradually however, and with the help of two other controversial figures-- Dan Harmon, Saline County's current prosecuting attorney, and his friend. law partner, and former assistant prosecutor, Richard Garrett--the parents' refusal to accept the official version of events brought some remarkable information to the surface.

The second autopsy revealed that, contrary to Malak's ruling, the boys had been wounded and probably were dead when they were placed on the tracks; Henry with a stab wound in his back, and Ives with a crushed skull.

Moreover, the grand jury that ordered the second autopsy found that almost every question asked relating to the boys' deaths had an answer that was tied in some way to the drug scene in Saline County. So many of the matters relating to drugs also touched upon local police activity that the jurors finally asked the stale police to investigate the possibility of police involvement further.

By the time a grand jury wrapped up its hearings into the deaths, no killer or killers and no motive had been identified. Instead, the foreman concluded, "We find that there is a tremendous drug problem that exists in Saline County ... "

That was in December, 1988, 16 months after the tragedy at the tracks. Since that time no county in Arkansas has been more loosely scrutinized, from the level of its elected officials to that of its known criminals, than Saline. And yet, even as the investigators buzzed about, the murders continued. Most were directly related to drugs, and, like the deaths of Don Henry and Kevin Ives, most remain unsolved.

The first of the possibly related deaths occurred during the summer of 1988, almost a year after the boys' deaths, near the time when their bodies were being exhumed. Keith Coney, a boy close to Don Henry and Kevin Ives in age, died when he ran his motorcycle into the back of an 18-wheeler on Interstate 40. Coney came from a large family, and one of his brothers had been with Henry and Ives on Geyer Springs Road in Little Rock the evening before they died. But whereas Don Henry and Kevin Ives were fairly ordinary teenagers, Coney was known as a troublemaker.

Pearson admits considering his death an improvement. "He was what we in law enforcement used to call a dirtball," she says. She relates that once, after she'd arrested Coney on an outstanding warrant, he sent his brother to her with the message that, "One of these days he was going to slit my throat and piss on my face as I died." She adds, "So no, I can't say as I was upset to hear what happened to him." What happened to Coney, according to reports collected by the state police, was that he was fleeing for his life and being chased when he died. Pearson said she heard from other deputies that Coney's throat had been slit; he'd jumped on his bike, and was apparently being chased by his attacker when he lost control and veered into the semi.

| What happened to Coney, according to state police

reports, was that he was fleeing for his life and being chased

when he died. ••• |

Douglas Wade "Boonie" Bearden, a young man who was also believed by police to be involved in drug-dealing and burglaries, told the state police when they interviewed him that two days before Coney died, Coney had said that he believed police were involved in the boys' deaths. Coney's body was never sent for an autopsy. His death was treated as a traffic fatality.

There is another link connecting Coney 's death with that of the boys. At the time of his death, several witnesses have testified, Keith Coney was selling drugs for a local used-car dealer by the name of James Calloway. According to testimony, Calloway also was indirectly tied to at least one of the men the ambulance driver encountered in the woods the night of the boys' deaths, the ones who said they were Alexander firemen.After the incident was finally reported, the men were identified as Tommy Lee Madison, Allen Smith, and Gary PuIlion, all of Alexander. Madison, who was later indicted on charges of possession of a controlled substance, told federal officials that he regularly purchased cocaine from PuIlion and another Alexander man named Ken Cook. Like Coney, Cook, according to several witnesses, also worked for Calloway.Even more intriguingly, Calloway knew both Don Henry and Kevin Ives personally. He was, in a way, responsible for their having met.

About six months before they died, Calloway's daughter had introduced the boys. She knew Kevin from school, and she'd grown up living near Don. As a youngster, he had played basketball and jumped on the trampoline in the back yard at Calloway's house.

(Calloway lost the house in a divorce settlement reached in the weeks just before the boys' deaths. His lawyer in those proceedings was Richard Garrett, the same man who later, as deputy prosecuting attorney, would revive the investigation into the murders.)

Curtis Henry says Calloway came by his house frequently in the days following the murders, asking how the investigation was going. At least one comment he made struck Marvella Henry as odd.

"He came down to the house," she recalls, "and he said, 'Curtis, I wonder if you didn't just beat up Don and put those boys on the tracks yourself." Of course, we were still in shock at the time, and I couldn't believe he was saying that. But then James has always been kind of uncouth.

"When Curtis asked him why he would say a thing like that, James sort of brushed it off. He said something like, "Oh, I've just been trying to figure out things that could have happened." Of course, that was long before we even knew that they 'd been beaten."

Keith McKaskle, another central figure in this murky case, was the next to die. This was in November of 1988, two days after Sheriff James Steed was defeated for reelection and at a time when pressure was mounting on the grand jury to name the boys' killers before it was forced by law to disband in December.

Unlike Calloway, who for a time had been a prime suspect in the boys' deaths, McKaskle had never been a suspect. His importance, as manager of a bar on the county line called the Wagon Wheel, was that he knew a lot of people.

Curtis Henry, Don Henry's father, considered McKaskle a personal friend. "He was working with me real regular," Henry says. "He knew everything, and when he found out something, he'd tell me."

Pearson also regarded McKaskle as "a very dear and close friend." "Before I got into law enforcement, I worked as a liquor store clerk on the county line," she says. "Keith was my protector."

She knew McKaskle used drugs, principally speed, and sold some on the side, but says that after she became a deputy, he never did drugs nor mentioned them in her presence. "Maybe it's not exactly the way things ought to be done," she says, "but Keith gave me a lot of good information on things I was investigating, and in exchange for that, I turned a blind eye to some things I might not have approved of."

McKaskle was friends with a number of policemen. He seems to have had the same tolerance-for-information relationship with all of them.

One of the pieces of information Pearson says McKaskle passed on to her concerned Dan Harmon, the county's present prosecuting attorney, and Richard Garrett, Harmon's law partner and the former assistant prosecutor. "I was one of the ones who got the investigation into Harmon and Garrett started," Pearson says. "Keith was the one who told me about Harmon. He told me I might want to watch Dan Harmon, that he was one of our largest suppliers."

She notes that while an investigation turned up extensive testimony that Harmon had once used and distributed drugs, police could find no evidence that he was presently involved in these activities. She says, "We couldn't get anyone to say he's still dealing." (Arkansas Times, July 1991)

Pearson remembers learning of McKaskle's murder when James Steed, the newly defeated sheriff, came into the office and announced, "You ain't gonna believe who just got his damn throat cut." She went to the scene and soon after Harmon and Garrett arrived together.

Garrett described McKaskle for reporters as "an extremely intelligent

and knowledgeable man, able to communicate with all levels of society."

He acknowledged that McKaskle had been cooperating in the investigation

into the boys' deaths; he had been asked to "keep his ears open" and

pass along "bar talk." Garrett said he had recently interviewed

McKaskle's about the case but that his information had not been

"spectacular," certainly "nothing worth getting killed over."

But somebody found McKaskle worth killing. His body was found in the

carport of his home at Benton. He'd been stabbed 113 times--every wound

above the waist--during what appeared to have been a ferocious fight for

his life. Pearson says his hands and arms were covered with "defense

wounds."

Around the county line, McKaskle's fighting ability was almost

legendary. Forty-four years old, 6-foot-2, and 205 pounds, he'd run

liquor stores and bars most of his life. He was reputed to be able to

c!ear out a bar unarmed and single handed. In the early 1980s he was

sued by a man who said he almost killed him while breaking up a fight.

Pearson was stunned by his death, and stunned again when investigators

announced within 24 hours that they'd solved the case. Hours after

discovery of the murder, the parents of a 19-year-old boy across the

street told Garrett that their son, Ronald Shane Smith, knew something

about what happened.

Within hours, Shane Smith, who stood 5- foot-11, weighed 180-pounds,

with a lower than -average IQ and no previous criminal record, was

arrested and charged with the murder. Smith had lived across the street

from McKaskle for 12 of his 19 years, he'd mowed McKaskle' s yard for

many of those years, and had bought his coin collection from McKaskle.

Ronnie Smith, Shane's father, says they brought the boy forward as a

witness and one of the victims of the crime, and instead, the police

pinned the on him.

While it's apparent Smith was at the scene of Kaskle's slaying--police

found his bloody clothes nearby--he has consistently denied being the

killer. Smith told police he was ·waiting for McKaskle when he got off

work because he'd arranged to buy a silver tray from him. It was dark in

the driveway-- it turned out a light bulb had been removed--and McKaskle

was at first startled to find Smith there.

The men entered the kitchen together and were followed in immediately

by three men caring guns and wearing black suits and masks. Only one man

spoke. He put a gun to Smith's head and ordered him to stay in the

kitchen. The men then ordered McKaskle outside, where, after a few

seconds of silence, Smith heard the sounds of a struggle, Mckaskle's

screams for help, and then silence again.

Smith said the men then ordered him outside, but when he got to the

door they pushed him forward so that he fell on McKaskle's

still-breathing body. He said they then put a knife in his hand,

photographed him, laughed and told him he was an accessory, and then

threatened him with death if he talked. Smith told police he had

slightly varied his initial accounts of what had happened out of fear of

retaliation.

The case against him was thin, laced with contradictions. Based

entirely on circumstantial evidence, it lacked witnesses, a confession,

a murder weapon, and a motive. Nonetheless, in announcing that the

murderer had been caught, Rick Elmendorf, the Benton chief of police,

also stressed that, "Nothing at this point has led us to believe this is

connected to the Henry and Ives case." And Don Birdsong, the state

policeman investigating the boys' deaths, quickly agreed.

"There is nothing linking this case with the Don Henry and Kevin Ives case," Birdsong said the same day, "nothing at all. Speculation that there was hurts the investigation into the train case [because) if anyone had information on the Ives-Henry deaths, he will be afraid to come forward if he believes McKaskle was killed because he was an informer."

| Somebody

found McKaskle worth killing. He was stabbed 113 times during

what appeared to have been a ferocious fight for his life. ••• |

More than a few people, including Pearson, believe to the contrary,

that stifling talk and perhaps sending an intimidating message to Larry

Davis, the newly elected sheriff, is exactly why McKaskle was killed. "I

will never believe that Shane Smith attacked Keith McKaskle and that

Keith could not have fought him off. I've seen Keith in too many fights,

and none of them lasted long. I think he was killed to send out a

message-to keep your mouth shut."

Pearson says that McKaskle believed he was being followed in the weeks

prior to his death, and that he also believed the investigation into the

Henry and Ives deaths was nearing a solution. "We'd talk about ii, and

he'd say, 'Don't worry about it, Baby, it's all going to come out before

long."

At the trial, prosecutors stressed Smith's bloody clothes, the fact

that McKaskle's silver tray was found in Smith's possession, and Smith's

inconsistent stories. Smith's attorneys defended him by trying to

introduce evidence that would throw doubt on the possibility that Smith

alone could have killed McKaskle. They noted, for instance, that a clump

of hair found in McKaskle's left hand did not match either his own or

Smith's, and that a bloody hand print found inside the house did not

belong to Smith. They tried to present other evidence, including some

that would impugn the testimony of Dr. Fahmy Malak, but Circuit Judge

John Cole ruled that evidence inadmissible. The jury convicted Smith of

second-degree murder and sentenced him to 10 years.

But just as the accidental-death theory didn't close the book on the

Henry-Ives · case, neither did the conviction of Shane Smith close the

book on the murder of Keith McKaskle. In many ways, the testimony that

was barred from the trial was as remarkable as the evidence overlooked

or ignored in the earlier case. When Smith's lawyers appealed, citing

the nature and amount of testimony that wasn't admitted, the Arkansas

Court of Appeals overturned Smith's conviction. This is what the jury

had not been allowed lo hear:

- Any testimony about McKaskle's physical prowess. The defense had listed 32 potential witnesses ready to describe what one called McKaskle's "supernatural" pugilistic abilities.

- Testimony that one month before the murder an Alexander man had been offered $4,000 to kill McKaskle.

- The testimony of David Hart, a former Cammack Village police

officer, who said McKaskle had asked him weeks before he died, "who in

Saline County he could trust to give some information to." Hart, who

said he told McKaskle he didn't know who could be trusted in Saline

County, also testified that McKaskle feared for his life "because he

knew something about the train thing."

- Testimony that within a few hours of his death McKaskle had used

"crystal," a methamphetamine, to stay awake "because somebody was

after him." Malak reported finding no traces of drugs in McKaskle's

body.

- And the testimony of four witnesses who claimed that McKaskle had

told them he was being followed and feared for his life. Witnesses

have said that on the night before he died, as McKaskle was watching

the election returns for sheriff on TV, he look two pennies out of his

pocket, threw them on the bar, and said, "If Steed loses tonight, my

life isn't worth this much."

Authorities had until mid-December to file new charges against Smith. As of the first of the month they had failed to do so. And so the McKaskle case lingers on, as dark as the driveway where he was killed.

Upon being sworn in in January of 1989, sheriff Larry Davis pledged to do whatever it took to solve the mystery of the Henry and Ives deaths. So far, though a lot of allegedly minor drug dealers were recently rested in a highly publicized sweep, the sheriff's office has apparently moved no solving its most notorious cases. In time, the deaths continued.

The very month Davis was sworn in, in January, of 1989, Gregory Allen "Fat Greg" Collin, 26, was found killed by a shotgun blast the face in rural Nevada County. Month, earlier, Collins had been subpoenaed to testify before the now-disbanded grand jury, but had not appeared.

After Collins' death.several witnesses told state police investigators that Collins was a drug user who'd participated in burglaries with Boonie Bearden (the same Boonie Bearden who'd told police about Keith Coney alleged suspicions of police involvement in the boys' deaths just prior to Coney's own death). Intriguingly, less than three month, earlier, Collins' mother had been found shot to death with a .38 caliber pistol blast to the chest at a deer camp in Dallas County. No one had witnessed the shooting, and he death had been ruled a suicide. Now, on the heels of her son's murder, some people were ginning to wonder.

For a time, an Alexander man, Clark Farmer, who'd also been questioned in connection with the Henry and Ives deaths and who was reportedly a friend of Keith Coney, was considered a prime suspect in "Fat Greg" Collins' death. But he was never brought to trial, and so far, that death too remains unsolved.

Collins died in January. In March, Bearden disappeared. Acting on a tip, police found his shirt floating in the Arkansas River, at Tar Camp, near Redfield, where the anonymous caller said be had been murdered.

But Woodrow May, an admitted drug dealer now in the state penitentiary, says Bearden, who was about 19 at the time, was also very 'smart. Besides being a close friend of the Hot Springs drug dealer who's been implicated in both Coney's and Collins' deaths. Bearden has himself been named as a suspect in the Henry-Ives deaths, as well as in the burglaries of several Louisiana discount stores.

May says he believes Bearden may have conveniently "disappeared," an assessment with which Pearson agrees. "Boonie was right in the middle of all of it," she says, "but I don't think Boonie's dead."

The next month, on April 3, 1989, another Saline County man, 21-year-old Jeff Rhodes, disappeared. Two weeks later Rhodes' charred body was found in a dump near Benton. He'd been shot once in the head, and his body had been mutilated with a knife.

Sheriff Davis said, "We have no idea who killed Rhodes or any motive for his death." Before the body was found, however, Rhodes' father had come up from Texas to help in the search. During that time he told reporters that during a phone call two weeks earlier bis son had told him he had to get out of town because he knew about the Henry, Ives, and McKaskle murders.

According to court testimony, Rhodes had been dealing drugs for a Benton cocaine supplier named Ron Ketelsen. A man named Frank Pilcher Jr. was convicted of Rhodes' s death, but before being sent off to serve his time, Pilcher reportedly named Ketelsen's son Jordan as the person responsible for McKaskle's death. Within weeks of Rhodes' death, Jordan Ketelsen was arrested in Carthage, Texas driving a van registered to his father in which police found more than 400 grams of cocaine.

In the summer of '89, two years after Don Henry and Kevin Ives died, yet another suspect in their deaths, Richard Winters, was gunned down in what appeared to be a robbery staged to cover a murder. The year before, Winters had been called as the fourth witness to appear before the grand jury.

Like Coney, who died in the suspicions motorcycle crash, and Ken Cook, who was allegedly selling drugs to at least one of the men claiming to be firemen at the scene of the Henry and Ives deaths, Winters worked for James Calloway. According to testimony collected by the Arkansas State Police, prior lo his death, Winters had been "talking" about what happened to Don Henry and Kevin Ives. One person interviewed said Winters had said he'd beaten the boys, another reported he had actually killed them.

(Claims of that sort were regarded as leads, but they were also one of the problems state police investigators ran into in this case. Literally dozens of people have been reported claiming credit for the murders. Pearson says boasting of responsibility for the murders became a popular tool of drug dealers wanting to help assure that they were paid.)

It has never been established whether Richard Winters' claims were idle talk or not He died while participating in an armed robbery of a crap game in Lonoke County. When Winters and an accomplice broke in, one of the intended victims, apparently not surprised, opened fire with a 12-guage sawed off shotgun.

Calloway, who is said to have planned the burglary, is now serving time in a federal prison in Texas for providing the supposedly intended victim of the burglary with the gun that was used to kill Winters.

Authorities in Saline County continued to insist that the mess of drugs and murders that plagued the Benton area were being aggressively investigated. But solutions were in short supply.

In June of 1990, another of Benton's convicted drug dealers--convicted in Texas not in Arkansas--was found shot to death in the driveway of a house near Lake Hamilton in Garland County. Jordan Colin Ketelsen, 21 the son of reputed drug-dealer Ron Ketelsen and the man named as a suspect in the stabbing death of Keith McKaskle, died of a single shotgun blast to the head. Garland County sheriff's deputies ruled the death a suicide.

Ketelsen 's girlfriend said she'd witnessed the shooting. There was no further investigation.

But Ketelsen's death warranted a closer look. His drug contacts, his having been named as the person behind McKaskle's murder, and the fact that the lone witness had told police a week earlier that Ketelsen had beaten her--all raised reasonable suspicions. Shane Smith's parents, for instance, would like to have known If his hand print matched the bloody print found in McKaskle's house. But no print was taken, and no autopsy was ever performed. Nor will one ever be in this case; the body was cremated within days.

Don Henry. Kevin Jves. Keith Coney. Keith McKaskle. Greg Collins. Boonie Bearden. Jeff Rhodes. Richard Winters. Jordan Ketelsen. And maybe the list goes on.

While nobody knows for certain that any of these boys or men died because of drugs, there's a high probability that they did. Even the boys on the tracks. After their deaths, Gayla Henry, Don's sister, told police she knew her brother had tried acid, and some witnesses told the state police the boys had promised they would have some cocaine for sale the day after they were found dead.

| While

nobody knows for certain that any of these boys or men died

because of drugs, there's a high probability they did. ••• |

If they did actually try to make some money on drugs, they were tapping into a vast and treacherous business. one that had already swallowed up boys like Coney, Collins, Bearden, and Rhodes. According to police informants, Gayla Henry's boyfriend at the time was also selling drugs. And so was at least one local police officer. He was indicted by the grand jury but left the state before charges were filed. If the mystery of the Henry and Ives deaths is ever solved, the key will likely tum upon a missing half-hour in the life of Don Henry, hours before it ended.

Between 11:30 and midnight, Kevin dropped by his next door neighbor's house.

Tim McCauley, who was Kevin's age and one of his closest friends, told police he saw Kevin in his car in the driveway and went out to talk with him, something they often did before going home for the night. The conversation was unremarkable, McCauley said, Kevin "didn't act scared or like anything was wrong." McCauley told police that, "When Kevin left he said, 'I've go to run. 'He didn't say where he was going."

At 12:30 a.m. the boys were seen together at the Roadrunner service station at Bryant They then went to the Henry home told Curtis Henry they were going hunting and left the house at about one. That was apparently the last time they were see alive except by their murderers.

But no one has ever determined where Don Henry was during the time when Kevin was visiting Tim McCauley. Two witnesses told police they saw Don at the stock car races near the county line. But one of those witnesses later changed his story and denied having seen Henry at the track. That witness was Charles Beck Jr, one of Don's closest friends.

According to testimony collected at the prosecutor's hearing and given to the state police, Beck denied having been with the boys he night they were killed. But questions about Beck's testimony linger.

Curtis Henry was in bed when the boy came by the house. Only Don came into the bedroom to tell him where they were going Curtis Henry knows Kevin Ives was there but to this day he wonders if someone else was with them.

Within weeks after the killings, testimony developed that Beck had indeed been in the woods that night with the boys. A 13-year old girl named Sharon Liggans told Tallent that one of her girlfriends, Beck's cousin had said Beck told her he had been with Don and Kevin and that "two black guys threat end her cousin if they said anything about knocking the boys in the head and tying them to the tracks.'' That account is interesting in hindsight because it came so early in the case--nearly six months before the ambulance driver first related her encounter with the men in the woods at the prosecutor's hearing-and almost a year before the second autopsy would reveal that the boys had indeed been hit in the head.

When called before the prosecutor's hearing months later, Liggans repeated her testimony. However, when the cousin was called to testify, she denied ever having said that Beck mentioned being with the boys.

When Beck was called to testify, he confirmed that he and Don Henry went spotlighting together "all the time," usually along the tracks near where the bodies were found . He acknowledged he'd intended to go with them the night of the murders, but said he'd forgotten and gone to the stock car races instead. He repeated that account later to the grand jury. But the following year, after the deaths of Coney and McKaskle, when asked by the state police to take a polygraph test regarding his testimony, Beck refused.

"A lot of people are afraid to talk," Pearson says. She includes among those who have a right to be afraid Jean Duffey, the former head of the Saline County Drug Task Force, who has been in hiding for the past months, refusing to testify before another grand jury.

"I don't blame Jean Duffey a whit for getting out of here," Pearson says. "That woman's life wouldn't be worth a flip if she was still around. Jean found out things on a lot of political officials, and that made her dangerous. Yeah, she was a little crazy, but you have to be to be in this work. I was too."

Whether there was a third person present or not, both of the boys' fathers are convinced that whatever happened to their sons--the encounter that ended with a knife in Don's back and a lethal blow to Kevin's head--happened at or near the spot on the tracks where their dismembered bodies were found. They have been over the possibilities a thousand times:

- that the boys stumbled upon a marijuana patch or an illegal operation and were killed for their curiosity;

- that they had earlier found or found out about a marijuana patch or drug drop, possibly from a passing train, and were killed by the dealers for whom the package was intended;

- that somebody intended to rough them up, perhaps over a debt, and the incident got out of hand;

- or even the possibility that the whole tragedy had nothing to do with drugs.

Whatever the scenario, Curtis Henry thinks it more than likely that the boys knew the person or persons who killed them. "Don hunted all his life," he says. "It was August, dry. There ain't no way you could have slipped upon him. And he was armed. I think you would have had to have known them."

But despite all the speculation, and all their efforts, and all the time that has passed, they still don 't have any answers. And that's hard. "I'm convinced that my son is dead and gone," Curtis Henry, says, "and that the sheriff's office screwed it up and that Malak finished screwing it up. And after that, I'm not convinced of anything."

All the parents feel betrayed by the legal system, both county and state. And, like Pearson and countless others who've watched the sorry spectacle unfold, they've learned to distrust authority. "There's two things I do not trust,"Curtis Henry says today. "That's a law officer and a state medical examiner."

"Hell, I can deal with the drug dealers," says Pearson. "They're two-faced and they'll tell you that. But a dirty cop is somebody you're supposed to be able to trust."

Finally, there is this. Five weeks before the death of Keith McKaskJe, in September of 1988, Richard Garrett, the deputy prosecutor, and Mel Hanks, a reporter for Little Rock's KARK-TV, received a cleanly typed, unsigned letter with a Little Rock postmark. The writer said he or she "felt" the information contained in the letter while reading a newspaper article about the murders. Harmon dismissed the letter as the apparent writings "of an amateur psychic." But its contents remain an intriguing element of this long and bizarre saga.

The letter said the boys were attacked by two men, one about 6-foot-2 and weighing 240 to 250 pounds, and the other between 5- 6 and 5-8, weighing 145 pounds. It said the incident took place below a large embankment by an old structure that has since been torn down. The writer said the boys tried to run to the tracks, about a half-mile away, but the men caught up with them. One of the boys was hit with what the writer described as "a large piece of bumper," while the other was knocked unconscious and tied up with blue plastic rope.

"The large man knew the boys personally," the teller writer said. "The small boy said his father would kill both the men if he knew."

Was the letter, as Harmon suggested, the work of a meddlesome amateur psychic? Or was it an attempt by someone too frightened to come forth publicly to pass along some information?

As with so much of this case, we will probably never know. Hanks found a site near the tracks that closely matched the description in the letter. But he says results of an analysis of the letter which was supposed to have been performed by the state police have never been released. When he called the state police to ask why, he was told the letter--like the tarp at the beginning of this case--has disappeared.

Reproduced with Permission

Top ↑